The use of light as an adjunct to in-office bleaching is a controversial topic in dentistry because of the equivocal outcomes of the research conducted in studies using light compared with no light treatment. The proper diagnosis and treatment planning of discolored teeth is of primary importance when managing the outcomes and setting expectations for patients undergoing in-office bleaching with supplemental light. Although no study is conclusive on all bleaching lights, research evidence provides guidelines for the responsible use of in-office bleaching lights in dentistry.

E.P. Wright, the nineteenth-century dental researcher and scholar, stated that “there is no higher glory for one who professes the healing art [of dentistry] than of preserving the natural tissues.” He published a paper in 1890 entitled “bleaching of discolored dentin practically considered.” His sentiment still rings true and this is why nearly 120 years after his publication the conservative nature of the in-office bleaching procedure still appeals to both patients and dentists alike. However, unlike those early years of bleaching when the procedure was preserved for severe discoloration, usually a single tooth caused by the loss of vitality, it is now common to perform complete dental bleaching on vital teeth. Vital bleaching was introduced to the profession in 1989, using 10% carbamide peroxide in a custom bleaching tray for at-home use. The dental bleaching procedure was no longer reserved for the single discolored tooth, but multiple vital teeth could be whitened for cosmetic reasons as patients presented with mild to moderate stains on all the teeth.

Although home-based whitening methods and materials have a prominent place in the dental market, in-office bleaching for vital teeth, especially with the use of adjunct light, has seen a steady increase in popularity in the last decade. The use of light as an adjunct to whitening has most likely seen its demand increase because of the extensive marketing that has occurred and the visibility of the procedure outside the dental office. For instance, whitening with supplemental lighting appears on television reality shows, billboards, and at kiosks in shopping malls.

Light-assisted, in-office bleaching methods use higher concentrations of peroxide in conjunction with supplemental light to enhance the effect of tooth whitening. These methods tend to appeal to patients who have a desire for rapid results and perhaps those not interested in wearing custom trays at night or those not successful with over-the-counter products. Dentists must be informed about the advantages and disadvantage of these methods and be able to make decisions for offering in-office bleaching with adjunct light based on sound evidence and well-controlled scientific studies.

Professional supervision: diagnosis and regulation

Important issues surrounding the use of whitening lamps to bleach teeth revolve around the concern for the health and safety of the patient. The appearance of tooth-whitening kiosks in malls, salons, and other nondental settings has caused some states to take action in banning nondental businesses. Although the employees of these businesses may wear white coats or scrubs and call themselves teeth-whitening professionals or cosmetic teeth-whitening specialists, they typically have no dental education. Proponents of light-assisted whitening outside the dental office may claim their services fall within the definition for cosmetic of the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA). However, states such as Alabama for example have been successful at making the case that these businesses are practicing dentistry without a license.

The cases against nondental providers are not directly against the administration of bleaching agents because the employees typically have the patients insert the product in their own mouths, but against a lack of training in matters such as treatment planning, sterilization, infection control, pain management, and emergency procedures, including the management of allergic reactions. In late 2009, the American Dental Association petitioned the FDA to establish appropriate classifications for tooth-whitening chemicals. Until the laws are clarified, state dental boards continue to work through their legislatures to ensure the health and safety of the people who resort to tooth-whitening services provided in nondental settings.

In the dental office, tooth whitening begins with a proper examination to screen for the presence of any dental disease. In addition to radiographs to rule out endodontic disease or decay, a treatment plan must be formulated to manage existing restorations, and the cause of the discoloration must be determined to initiate an effective bleaching strategy.

Case selection/minimizing risks and side effects

A through clinical examination should reveal not only cases that are suitable for in-office bleaching with adjunct light, such as teeth with mild to moderate discoloration ( Fig. 1 ), but also teeth that are not suitable using this method, such as the single discolored tooth ( Fig. 2 A) or the patient who presents with teeth beyond the shade of the lightest tab on a standard shade guide (see Fig. 2 B). The patient who presents with severe intrinsic staining (see Fig. 2 C) may also be better served with long-term at-home bleaching.

Greater tooth sensitivity has been reported with in-office bleaching with adjunct light compared with no light. Risk factors for sensitivity, such as existing decay, gingival recession, cervical abrasions, or a history of sensitivity, should be identified during the review of the patient’s dental history. Patient identified with existing tooth sensitivity may prebrush for about 2 weeks with a toothpaste containing potassium nitrate to help minimize sensitivity. Patients can also be provided with 600 mg of ibuprofen 30 minutes before the in-office procedure to help reduce sensitivity. However, a recent study showed that patients who received ibuprofen 30 minutes before an appointment compared with patients who received a placebo capsule reported the same level of sensitivity 1 hour after the in-office procedure, which continued up to 24 hours. This finding means that additional doses of ibuprofen may be necessary after the in-office bleaching procedure to prevent postoperative sensitivity. Applying 4% to 6% potassium nitrate gel on the lingual surface of the teeth during the appointment is another strategy to minimize tooth sensitivity.

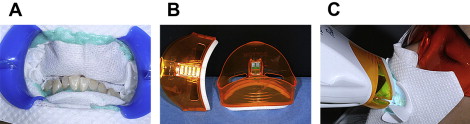

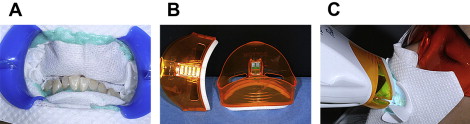

Concentrations of hydrogen peroxide between 15% and 40% are used for professional in-office bleaching, which poses a risk of chemical tissue damage. Also the human eyes and oral soft tissue should be protected from the blue light or ultraviolet (UV) radiation emitted from the bleaching light. A recent study reported the health risk from optical radiation of 7 commercially available bleaching lamps. This study reported that most of the lamps exceeded the standards set for exposure limits for direct blue light to patients’ eyes before the recommended treatment times had elapsed. One light even exceeded the exposure limits set for reflected blue light within the recommended treatment time. Although the potential health risk for emission of blue light and UV hazard were all classified as low to moderate-low risk according to safety standards, these findings highlight the importance of proper barriers on all exposed tissues ( Fig. 3 A). Also to minimize reflective radiation, protective light guides surrounding the end of the light source are recommended (see Fig. 3 B), and protective eyewear for patients is essential (see Fig. 3 C).

Case selection/minimizing risks and side effects

A through clinical examination should reveal not only cases that are suitable for in-office bleaching with adjunct light, such as teeth with mild to moderate discoloration ( Fig. 1 ), but also teeth that are not suitable using this method, such as the single discolored tooth ( Fig. 2 A) or the patient who presents with teeth beyond the shade of the lightest tab on a standard shade guide (see Fig. 2 B). The patient who presents with severe intrinsic staining (see Fig. 2 C) may also be better served with long-term at-home bleaching.

Greater tooth sensitivity has been reported with in-office bleaching with adjunct light compared with no light. Risk factors for sensitivity, such as existing decay, gingival recession, cervical abrasions, or a history of sensitivity, should be identified during the review of the patient’s dental history. Patient identified with existing tooth sensitivity may prebrush for about 2 weeks with a toothpaste containing potassium nitrate to help minimize sensitivity. Patients can also be provided with 600 mg of ibuprofen 30 minutes before the in-office procedure to help reduce sensitivity. However, a recent study showed that patients who received ibuprofen 30 minutes before an appointment compared with patients who received a placebo capsule reported the same level of sensitivity 1 hour after the in-office procedure, which continued up to 24 hours. This finding means that additional doses of ibuprofen may be necessary after the in-office bleaching procedure to prevent postoperative sensitivity. Applying 4% to 6% potassium nitrate gel on the lingual surface of the teeth during the appointment is another strategy to minimize tooth sensitivity.

Concentrations of hydrogen peroxide between 15% and 40% are used for professional in-office bleaching, which poses a risk of chemical tissue damage. Also the human eyes and oral soft tissue should be protected from the blue light or ultraviolet (UV) radiation emitted from the bleaching light. A recent study reported the health risk from optical radiation of 7 commercially available bleaching lamps. This study reported that most of the lamps exceeded the standards set for exposure limits for direct blue light to patients’ eyes before the recommended treatment times had elapsed. One light even exceeded the exposure limits set for reflected blue light within the recommended treatment time. Although the potential health risk for emission of blue light and UV hazard were all classified as low to moderate-low risk according to safety standards, these findings highlight the importance of proper barriers on all exposed tissues ( Fig. 3 A). Also to minimize reflective radiation, protective light guides surrounding the end of the light source are recommended (see Fig. 3 B), and protective eyewear for patients is essential (see Fig. 3 C).

Setting expectations of treatment time

When reviewing treatment options and setting expectations with patients regarding bleaching vital teeth, we must first discuss the advantages and disadvantages of in-office versus at-home techniques. The primary advantage most sought after from patients attracted to in-office bleaching is the expectation of rapid results. The question of how much time is saved with in-office techniques is not easy to answer, because results can vary among patients and depend on the cause of the stains, but some general expectation should be discussed based on available clinical evidence. Seven days of at-home bleaching with 10% carbamide has been shown to be equivalent to 3 15-minute applications of 38% hydrogen peroxide or 5 days of at-home bleach and 1 hour’s treatment with 28% hydrogen peroxide with supplemental light. A combination technique of in-office bleaching plus home bleaching has been shown to be more effective than in-office bleaching alone. Bernardon and colleagues compared the clinical efficacy of home bleaching, in-office bleaching (with and without light), and a combination technique of in-office bleaching plus home bleaching. The home bleaching was performed with a take-home custom tray using 10% carbamide peroxide worn for 8 hours a day for 2 weeks. The in-office bleaching was performed using 35% hydrogen peroxide for two, 45-minute sessions, whereas the combination technique was performed with one, 45-minute session with supplemental light followed by home bleaching. Color measurements after the first week showed better bleaching results with in-office bleaching with light or the combination technique compared with the at-home bleaching alone. After 2 weeks, there was no significant difference among the 3 techniques. Realistic expectations should also be set about the final whitening effect, and the patient should be informed that the immediate outcome may be lighter at the outset and rebound to some extent within the first week. If the dentist prescribes a combination technique with which the patient begins to supplement the in-office treatment with at-home bleaching, then the patient may not experience the rebound effect. Postoperative instructions may include a recommendation to wait a minimum of 6 hours after in-office bleaching before drinking any chromogenic drinks.

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses