Introduction

Comprehension of informed consent information has been problematic. The purposes of this study were to evaluate the effectiveness of a shortened explanation of an established consent method and whether customized slide shows improve the understanding of the risks and limitations of orthodontic treatment.

Methods

Slide shows for each of the 80 subject-parent pairs included the most common core elements, up to 4 patient-specific custom elements, and other general elements. Group A heard a presentation of the treatment plan and the informed consent. Group B did not hear the presentation of the informed consent. All subjects read the consent form, viewed the customized slide show, and completed an interview with structured questions, 2 literacy tests, and a questionnaire. The interviews were scored for the percentages of correct recall and comprehension responses. Three informed consent domains were examined: treatment, risk, and responsibility. These groups were compared with a previous study group, group C, which received the modified consent and the standard slide show.

Results

No significant differences existed between groups A, B, and C for any sociodemographic variables. Children in group A scored significantly higher than did those in group B on risk recall and in group C on overall comprehension, risk recall and comprehension, and general risks and limitations questions. Children in group B scored significantly higher than did those in group C on overall comprehension, treatment recall, and risk recall. Elements presented first in the slide show scored better than those presented later.

Conclusions

This study suggested little advantage of a verbal review of the consent (except for patients for risk) when other means of review such as the customized slide show were included. Regression analysis suggested that patients understood best the elements presented first in the informed consent slide show. Consequently, the most important information should be presented first to patients, and any information provided beyond the first 7 points should be given as supplemental take-home material.

Health literacy is defined as “the ability to understand and use health-related printed information in daily activities at home, at work, and in the community to achieve one’s goals and to develop one’s knowledge and potential.” This definition and approach showed low to intermediate health literacy in the United States. Lower health literacy in adults has been linked to poorer overall and oral health of the person and of his or her children.

Health care providers are responsible for ensuring that patients are well informed regarding the possible risks, benefits, costs, and alternatives of their treatment. In the case of orthodontics for minors, parents, who are the responsible party, should be well informed about their child’s treatment. To prevent problems such as litigation after electing treatment, education materials must be accessible, thorough, and understandable. Unfortunately, most health education and consent documents are complex and difficult to understand.

Many investigators have sought to improve medical consent procedures to increase patient understanding. The approaches and results varied. For a group of low-income parents consenting for their children, an enhanced print version of consent (with improved white space, descriptive headings, simplified language, and illustrations) was superior to audiovisual presentations. In contrast, an audiovisual consent method enhanced comprehension, compared with a verbal method for adult patients with lower education levels.

Current methods of informed consent for orthodontic treatment with written and verbal instructions are relatively ineffective, as evaluated by recall and comprehension among adolescent patients and their parents. Orthodontic informed consent research has shown that both patients and parents often have difficulty remembering specific reasons for treatment, procedures to be expected during treatment, risks of treatment, and patient and parent responsibilities during treatment. Ernst et al found poor recall scores for risks of treatment, need for retainers, and length of retention period.

In a study by Kang et al, a modified consent form combined with a slide show (a method with improved readability and processability) resulted in better recall and comprehension than when subjects were given a standard or modified consent form alone. However, correct responses ranged from only 44% to 67%.

Current informed consent methodologies face 2 limitations: the large amount of information presented to the patients and the length of the consent process. Learning research has shown that repetition and review of key points can help subjects better retain the important information in the informed consent. However, it is also possible that several reiterations can overwhelm and confuse patients and parents, or simply fatigue them.

There are several approaches that could further improve these newer, modified methods. These include reducing either the presentation length or the amount of information presented. The length of the informed consent presentation can be addressed by omitting some explanations. Concise medical consent forms with fewer words, shorter and simpler sentences, and easier readability did not limit patient understanding. “Chunking,” or placing like items together on a list or in a slide show, also might allow subjects to retain more than 7 new concepts in their short-term memory.

The purposes of this study were to compare an established, improved presentation of informed consent with a more concise presentation by using the same informed consent document, and to determine whether customized informed consent audiovisual materials with reordered items in the supporting computer-based slide show presentation can improve recall and comprehension of the risks and limitations related to orthodontic treatment.

Material and methods

The research protocol was reviewed and approved by the institutional review board of The Ohio State University.

New patients planned for comprehensive treatment at The Ohio State University graduate orthodontic clinic were recruited as subjects by staff and orthodontists at the time of orthodontic records or via a telephone call before their consultation appointment. Power analysis based on data from the previous study by Kang et al with a nondirectional alpha of 0.05 (SD, 19) indicated a sample size of 40 per group plus a 10% dropout factor would be appropriate to yield a power of 0.82. A total of 88 patient-parent pairs agreed to participate in the study. The final sample comprised 80 patient-parent pairs because of 8 withdrawals based on unanticipated language issues, an unrevealed learning disability, and the discovery that subjects had undergone previous orthodontic treatment.

The subjects were randomly assigned to the 2 intervention groups. All patients met the following inclusion criteria: 12 to 18 years of age, no previous orthodontic treatment, no sibling or other immediate relative previously treated at the clinic, patients and parents able to communicate in English, and no developmental disabilities or urgent medical conditions. All patients were accompanied by a parent or guardian able to consent for research and treatment, with legal guardianship for at least 1 year. These 40 patient-parent pairs in groups A and B were similar to each other and to the patient-parent pairs in the study of Kang et al in terms of demographics, orthodontic history, and health. The third group, group C, to which groups A and B in this study were compared, was from the study of Kang et al and included 30 patient-parent pairs.

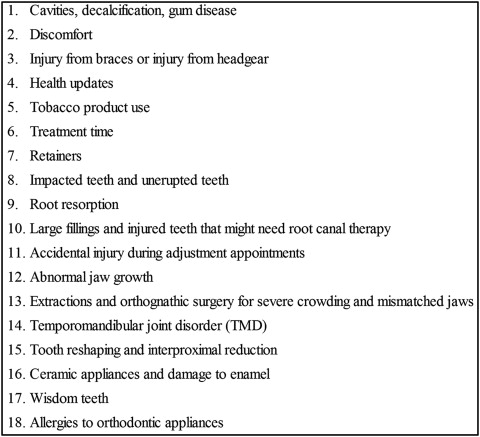

For this study, the modified informed consent document integrating 18 items or elements of informed consent ( Fig 1 ) created by Kang et al was used. The modified informed consent contained less medical and dental terminology, an active voice, larger font size, and balanced white space. The 18 elements were divided into (1) preventable risks, followed by a recommended action for preventing that risk; and (2) possible limitations of treatment.

The original PowerPoint (version 2003; Microsoft, Redmond, Wash) slide show created by Kang et al provided audio and visual cues reviewing the 18 elements of informed consent in the modified informed consent. For this study, these 18 elements were divided into 3 portions, or “chunks,” based on a variation of the concept presented by Doak et al. The chunks were (1) the 4 most common core risks associated with orthodontic treatment as supported in the literature: pain, external root resorption, enamel or soft-tissue destruction, and posttreatment changes ; (2) up to 4 custom risk factors that applied uniquely to each patient subject (selected by the orthodontist, including such potential risks such as impacted teeth or the need for jaw surgery); and (3) the remaining general risk factors. The slide show presented these elements from general to specific, with the core and custom risk factors placed at the end of the presentation. The subjects were unaware of this arrangement, and no attention was drawn to the importance or significance of the elements.

To evaluate the subjects’ recall and comprehension, a previously validated measurement tool composed of a series of open-ended questions that focused on the 18 elements of informed consent in the American Association of Orthodontists’ informed consent documents was used. The open-ended questions sought to assess recall and comprehension rather than memorization of informed consent. In the measurement tool, there were 4 rephrased recall questions aimed at testing the internal reliability of the subjects. Knowledge-based questions measured recall, and scenario-based questions measured comprehension by presenting a situation and asking the subject how he or she would manage it.

Research assistants were trained in research protocol, subject recruitment, the consent process, and the interview procedure. Interviews were conducted by using a script that incorporated the measurement tool. Interviewers repeated and rephrased questions as necessary and encouraged subjects to answer all questions without leading their responses.

For all subjects, the orthodontist verbally reviewed the reasons for the recommended treatment and the orthodontic treatment plan during the scheduled consultation appointment with the patient and the parent. For group A, the orthodontist verbally reviewed the risks and limitations of treatment in the modified informed consent document with the patient and the parent. For group B, the modified informed consent was not verbally reviewed by the orthodontist. In both groups, the patient and parents were encouraged to read the modified informed consent form for 10 to 15 minutes on their own and were allowed to ask the orthodontist questions. Independently, the patients and parents in both groups then viewed the customized computer-based slide-show presentation and participated in a recorded interview with the research assistants. Group C was equivalent to group A except that all patient-parent pairs viewed an identically ordered slide show (which included the 18 consent elements).

The reading test portion of the Wide Range Achievement Test 3 (WRAT 3) (Wide Range in cooperation with Psychological Assessment Resources, Lutz, Fla) and the Rapid Estimate of Adult Literacy in Medicine (REALM) (Terry Davis, Louisiana State University Medical Center, Shreveport) were used to gauge overall reading ability and health literacy reading ability, respectively, of both patient and parent subjects. Additional information was obtained with a self-administered questionnaire for sociodemographic information, a self-assessment of understanding of the risks, benefits, and limitations of orthodontic treatment on a visual analog scale, and state anxiety level with a 6-item Spielberger State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI-6). Patients who participated in the study were given a $15 gift card.

Digital recordings of the interviews were transcribed. A previously developed codebook identified key words or phrases signifying recall and comprehension of the 18 elements of informed consent. The response rater (K.M.C.) reviewed and gained proficiency in using the codebook with its authors before scoring the interviews for this study. With the codebook, transcribed interviews were reviewed, and the responses were scored as either on target (correct) or off target (inappropriate, “I don’t know or cannot remember,” question skipped, or no response given). As more interviews were scored, additional acceptable responses were identified and added to the codebook; these responses were recoded for previous subjects.

Four elements in the recall portion of the measurement tool were rephrased to test the reliability of the patient and parent subjects. The response rater’s interrater reliability was evaluated by scoring 10 patient and 10 parent interviews chosen at random from the previous data set from Kang et al and compared with the scores of that study’s response rater. To assess intrarater reliability, 2 weeks after their original scoring, the response rater rescored 10 patient and 10 parent interviews from this study’s data set.

Statistical analysis

Simple kappa statistics with 95% CI were calculated for interrater (Kang et al vs our study), intrarater, and subject reliability values. Data from this study were combined with those from the study of Kang et al for the remaining analyses. Descriptive statistics were calculated for sociodemographic data, REALM scores, WRAT 3 scores, STAI-6 scores, and self-assessment scores. Between-group differences for these potentially confounding variables were evaluated by using analysis of variance (ANOVA) for age; the Kruskal-Wallis test for the REALM, WRAT3, STAI-6, and self-assessment scores; the chi-square test for sex; and the Fisher exact test for ethnic group and grade. Spearman correlation coefficients with Bonferroni corrections were used to calculate the correlations between mean percentages of on-target responses, REALM scores, WRAT 3 scores, STAI-6 scores, self-assessment scores, and between patient and parent on-target responses for recall, comprehension, domain, and question types. ANOVA and the Tukey-Kramer test were used to evaluate the following differences between groups A, B, and C: mean percentages of on-target responses for overall recall and comprehension questions; the domains of treatment, risk, and responsibility; and the core, custom, and general elements of the slide show. The α level was set at 0.05; consequently, differences were considered significant if the P value was <0.05.

To further investigate the effect of ordering and to determine whether there was a serial-positioning effect for groups A, B, and C, a second-order polynomial regression was applied to the percentages of correct responses that were aligned with the order of the elements in the slide-show presentation. Previously, Murdock and Bonk and Healy analyzed their serial-positioning data using curvilinear functions.

Results

Reproducibility for the scoring of the interview data, evaluated as interrater reliability (current rater vs previous rater), was excellent (κ = 0.85 [95% CI, 0.77-0.94]). Intrarater reliability for the interviews also was excellent (κ = 0.86 [95% CI, 0.79-0.92]).

Internal reliability ( Table I ) for all subjects in groups A and B was fair to substantial for 3 of the 4 questions, with kappa scores ranging from 0.22 to 0.67. The question regarding ankylosis had slight reliability, with kappa scores of 0.18 (children) and 0.19 (adults).

| Question | Parent kappa (CI) ∗ | Reliability | Patient kappa (CI) ∗ | Reliability |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Retainers | 0.41 (0.09-0.72) | Moderate | 0.51 (0.23-0.79) | Moderate |

| Health updates | 0.56 (0.11-1.00) | Moderate | 0.22 (–0.02-0.45) | Fair |

| TMJ/TMD | 0.67 (0.50-0.83) | Substantial | 0.51 (0.27-0.75) | Moderate |

| Ankylosis | 0.19 (0.04-0.34) | Slight | 0.18 (0.01-0.34) | Slight |

Combining our study data with those from the study of Kang et al for analysis seemed appropriate, since both studies were conducted at the same institution and sampled similar populations within 3 years of each other (when no changes in patient management and treatment procedures were instituted). The results demonstrated excellent interrater reliability and no significant differences among the combined treatment groups for sex, age, ethnicity, education or grade level, parental income, REALM, WRAT 3, or STAI-6 ( Table II ).

| Subject | Group | Sex | Age (y) (mean [±SD]) |

Educational level (median) |

Ethnicity ∗ (%) |

Income (median) |

REALM (median) |

WRAT 3 (median) |

STAI-6 (median) |

Self-assessment/ understanding (mean [±SD]) VAS |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patients | A | 67.5% F | 14.4 (1.5) | 8th grade | 66.7 WNH | 7th-8th | High | 9.0 | 8.10 (1.76) | |

| n = 40 | 32.5% M | 15.4 BNH | grade | school | ||||||

| 12.8 WH | ||||||||||

| 2.6 EA | ||||||||||

| 2.6 mixed | ||||||||||

| B | 55% F | 14.3 (1.6) | 8th grade | 72.5 WNH | High | High | 9.5 | 8.30 (1.69) | ||

| n = 40 | 45% M | 17.5 BNH | school | school | ||||||

| 7.5 mixed | ||||||||||

| 2.5 WH | ||||||||||

| C | 43% F | 14.6 (1.7) | 8th grade | 73.3 WNH | High | High | 10.0 | 7.46 (1.7) | ||

| n= 30 | 57% M | 20.0 BNH | school | school | ||||||

| 3.3 WH | ||||||||||

| 3.3 mixed | ||||||||||

| P value | 0.13 | 0.80 | 0.68 | 0.62 | 0.19 | 0.69 | 0.97 | 0.07 | ||

| Parents | A | 80% F | 41.9 (9.0) | <4 years | 74.4 WNH | $25,000- | High | High | 9.5 | 8.77 (1.25) |

| n = 40 | 20% M | college | 15.4 BNH | $49,999 | school | school | ||||

| 2.6 WH | ||||||||||

| 2.6 EA | ||||||||||

| 2.6 NA | ||||||||||

| 2.6 mixed | ||||||||||

| B | 80% F | 43.8 (8.2) | <4 years | 75.0 WNH | $50,000- | High | High | 9.0 | 9.17 (0.94) | |

| n = 40 | 20% M | college | 17.5 BNH | $74,999 | school | school | ||||

| 5.0 WH | ||||||||||

| 2.5 mixed | ||||||||||

| C | 80.0% F | 42.0 (6.6) | <4 years | 73.3 WNH | $25,000- | High | High | 7.0 | 9.02 (1.09) | |

| n = 30 | 80.0% M | college | 20.0 BNH | $49,999 | school | school | ||||

| 3.3 WH | ||||||||||

| 3.3 mixed | ||||||||||

| P value | 1.00 | 0.50 | 0.93 | 1.00 | 0.13 | 0.09 | 0.59 | 0.18 | 0.43 |

∗ WNH , White non-Hispanic; WH , white Hispanic; BNH , black non-Hispanic; BH , black Hispanic; EA , east Asian or Pacific Islander.

Correlations within studies were calculated between correct responses for question type (recall and comprehension for both patients and parents in groups A and B), scores on the REALM, WRAT 3, STAI-6, and the self-assessment of understanding. Only the REALM was positively correlated with the percentage of correct recall responses for the patients in group A (r = 0.60, P = 0.005). Self-assessment of understanding was not significantly correlated with correct responses for any group. Correlations were calculated among REALM, WRAT 3, STAI-6, and self-assessment of understanding by patients and parents. REALM and WRAT 3 scores were positively correlated for both patients and parents (r = 0.72 and 0.56, respectively; P = 0.005). No correlations (r = −0.03-0.40) were significant ( P = 0.09-1.0) for the on-target responses between patients and parents for recall, comprehension, domains, or question types.

For within study differences, the results of the comparisons between groups on percentages of correct responses for overall recall and comprehension are presented in Table III , and those for the domains of treatment, risks, and responsibilities for recall and comprehension are given in Table IV . The results of the comparisons between groups for question type by customization (general, core, or custom) are presented in Table V . The only significant difference between groups A and B was found in the risk domain for the recall questions for patients; the subjects in group A had higher scores than did those in group B. There were no significant differences between groups A and B for any question type or domain for parents.

| Subject | Group | Recall | Recall comparisons ∗ | Comprehension | Comprehension comparisons ∗ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patients | A | 58.8 (14.8) | X | 52.9 (15.8) | X † |

| B | 57.4 (13.4) | X | 53.6 (13.3) | X † | |

| C | 52.6 (14.4) | X | 44.2 (16.7) | Y | |

| Parents | A | 71.0 (13.9) | X | 67.1 (13.3) | X |

| B | 70.6 (13.9) | X | 69.2 (15.2) | X | |

| C | 67.3 (16.8) | X | 66.3 (16.6) | X |

∗ Similar letters indicate no statistically significant differences among the informed consent forms for either patients or parents by ANOVA.

| Subject | Group | Domain | Recall | Recall comparisons ∗ | Comprehension | Comprehension comparisons ∗ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patients | A | TX | 47.0 (19.3) | X,Y | 40.9 (24.5) | X |

| B | TX | 48.9 (19.0) | X † | 39.0 (20.0) | X | |

| C | TX | 36.7 (22.9) | Y | 32.7 (23.8) | X | |

| A | RK | 68.6 (20.6) | X | 41.6 (17.4) | X ‡ | |

| B | RK | 57.4 (18.5) | Y † | 38.9 (18.5) | X † | |

| C | RK | 51.3 (20.3) | Y ¶ | 28.1 (19.7) | Y | |

| A | RS | 67.4 (18.5) | X | 72.3 (17.8) | X | |

| B | RS | 68.6 (18.5) | X | 78.2 (15.5) | X | |

| C | RS | 70.7 (18.3) | X | 68.2 (23.0) | X | |

| Parents | A | TX | 60.8 (21.5) | X | 52.4 (22.8) | X |

| B | TX | 62.1 (27.0) | X | 59.6 (26.4) | X | |

| C | TX | 62.3 (24.5) | X | 56.4 (24.1) | X | |

| A | RK | 72.4 (17.4) | X | 58.2 (19.9) | X | |

| B | RK | 69.6 (19.3) | X | 57.5 (20.5) | X | |

| C | RK | 66.0 (22.0) | X | 52.2 (21.1) | X | |

| A | RS | 84.2 (15.7) | X | 85.6 (15.6) | X | |

| B | RS | 80.8 (15.9) | X | 86.8 (13.1) | X | |

| C | RS | 80.5 (17.8) | X | 87.0 (18.3) | X |

∗ Similar letters indicate no statistically significant differences among the informed consent forms for either patients or parents by ANOVA.

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses