Beyond the classic clinical picture of molar incisor hypomineralization, qualitative enamel changes are also increasingly observed in the primary dentition, primarily in the second primary molars. At present these teeth are named as hypomineralized second primary molars (HSPM). Previously, terms such as cheese five, MIH-d, or deciduous molar hypomineralization (DMH) were chosen.1

Weerheijm et al2 mentioned this form of hypomineralization among other variations in the permanent dentition already in 2003:

“Although the defects described as MIH can sometimes also be noticed on second primary molars, second permanent molars and tips of the permanent canines, the most frequent occurrence in children is that of first permanent molars.”

Compared to the classical presentation of molar incisor hypomineralization (MIH), examinations of second primary molars are rather poor. However, HSPM also requires early diagnosis and therapy.

This chapter provides an overview of this form of hypomineralization. In addition to current prevalence data, the etiological factors, clinical presentation, diagnostics, and current therapy options are explained in more detail.

17.1 Definition

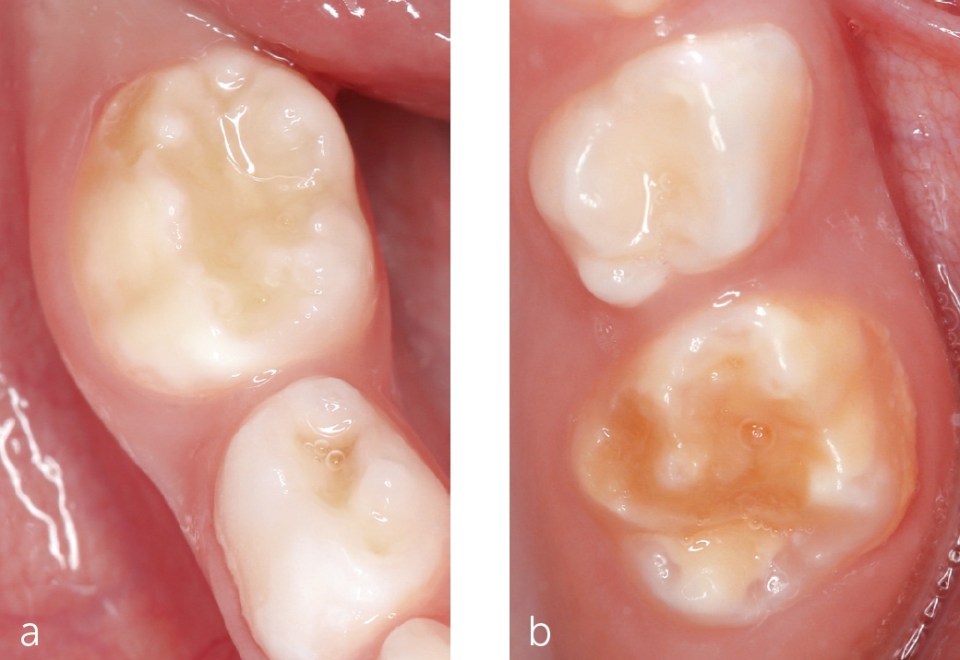

In general, enamel hypomineralization is defined as a qualitative defect of the enamel that is visually identifiable as an abnormality in the translucency of the enamel and is also characterized by a demarcated enamel opacity.3 This reduced mineralization can vary in severity and is characterized by white, yellow, or brown discoloration. In the permanent dentition, these hypomineralized teeth are known as molar incisor hypomineralization (MIH), while in the primary dentition they are called hypomineralized second primary molars (HSPM).3,4 HSPM is defined as hypomineralization of at least one and up to four second primary molars1 (Fig 17-1).

Fig 17-1 A 3-year-old female patient with HSPM of varying degrees in teeth 55, 75, and 85. a) Maxillary view: tooth 55 shows a white-yellow opacity with posteruptive enamel breakdown in the mesial region. Tooth 65 is healthy. b) Mandibular view: Tooth 75 shows a white-cream colored opacity with posteruptive enamel breakdown in the mesial region, tooth 85 is characterized by a white-cream colored opacity. c) Frontal view: It can be seen that the canines also show demarcated opacities.

17.2 Prevalence

Although there are not so many prevalence studies on HSPM, it can be assumed that it also occurs worldwide. Data are now available not only for Europe, but also for North and South America, Asia, and Oceania. Until recently, North America was missing on this list.

The figures currently vary between 1.6% and 21.8% for the second primary molars.5,6 Here, too, the figures differ from country to country. The average number is 7.9%.7

The wide range of the results can be explained to some extent by the different examination protocols and diagnostic criteria applied.8 However, recently published studies increasingly use the criteria and recommendations proposed by European Academy of Paediatric Dentistry (EAPD).8,9

17.3 Etiology

The etiology of hypomineralized second primary molars is considered multifactorial. The factors of genesis have not yet been conclusively clarified. As with MIH, socioeconomic influences are also discussed in the literature in addition to pre-, peri- and postnatal causes.

Potential prenatal risk factors include medical problems during pregnancy, eg, cigarette smoking,10 alcohol consumption,11 and in vitro fertilization.10 Currently, there is no clear evidence whether medication use during pregnancy (or subsequently in the infant’s first year of life) is also associated with the development of HSPM.12

Perinatal complications during delivery,13 and low birth weight11 have also been considered as possible causes.

Potential postnatal influences include medical problems in the newborn,13 febrile episodes in the child’s first year of life,11 acute childhood illnesses,13 and eczema in the first 18 months of life.10

In addition, possible socioeconomic factors such as ethnicity11 and socioeconomic situation10,11 are also discussed.

Figure 17-2 summarizes the different factors currently under discussion.

Fig 17-2 Etiological factors discussed for HSPM.

17.4 Diagnostics

Diagnosis is carried out using the criteria proposed by the EAPD.2,9,14

17.4.1 Demarcated opacities

Opacities can be white, cream, yellow, or brown. As in MIH, darker colors indicate more structurally weakened areas than lighter ones. The opacities are easily distinguishable from sound enamel14 and must be larger than 1 mm9 (Fig 17-3). The surface of the opacity is smooth.

Fig 17-3 Opacity. a) White opacity in the buccal region. b) White opacity in the occlusal region. The permanent molar also shows MIH. c) Extensive opacity in the vestibular-mesial-palatal area.

17.4.2 Posteruptive enamel breakdown

Since this is a qualitative enamel defect, initially formed enamel can breakdown and be lost in the reduced mineralization. This can occur shortly after eruption and is then called posteruptive enamel breakdown. Such enamel breakdowns frequently occur at the sites where the greatest masticatory forces act, ie, at cusps, occlusal surfaces and palatal areas in the upper jaw and buccal areas in the lower jaw. The margins of the defect are rough and irregular9 (Fig 17-4).

Fig 17-4 Posteruptive enamel breakdown. a) Small posteruptive enamel breakdown in the distobuccal region of the primary molar with an extensive white opacity. b) Posteruptive enamel breakdown in the occlusal-palatal region of the second primary molar.

Posteruptive enamel breakdown must be differentiated from hypoplasia. The latter is a quantitative enamel defect. In this case, the enamel is not adequately formed in its quantity from the beginning, resulting in smooth edges.

17.4.3 Atypical restoration

Children with HSPM may have large restorations that do not fit the usual picture of biofilm-related caries. For example, the restorations are found on smooth surfaces in the buccal or palatal region in an otherwise caries-free dentition9 (Fig 17-5).

Fig 17-5 Atypical restorations on both mandibular primary molars. Partial chipping fractures have already occurred again in the marginal area of the restoration on tooth 85. The patient also shows MIH in both mandibular permanent molars.

17.4.4 Atypical caries

Hypomineralized areas are more susceptible to caries. Enamel showing an opacity is weaker, and the rough surface of an enamel breakdown also makes it difficult to clean these areas. An atypical caries, caused by HSPM, also does not fit into the picture of biofilm-induced caries. Especially in the presence of large cavities, the occurence of caries on smooth surfaces of the second primary molars and (almost) caries-free first primary molars, HSPM must be considered. Often, an opacity is still visible at the margin of the breakdown9 (Fig 17-6).

Fig 17-6 Atypical caries.

17.4.5 Atypical extraction

In the case of severe caries decay, as well as extensive posteruptive breakdown of a hypomineralized second molar, or in the case of recurring pain, extraction of the tooth must also be considered as a treatment option. Atypical extraction of a second primary molar can be diagnosed in the absence of this tooth in an otherwise healthy dentition and the diagnosis of another second primary molars with hypomineralization9 (Fig 17-7).

Fig 17-7

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses