-

Chapter Outline

Learning Objectives

After reading this chapter, the student should be able to:

- 1.

Identify biologic aspects in the elderly patient that are similar to and different from those in the younger patient.

- 2.

Discuss age changes in the older dental pulp, both physiologic and anatomic.

- 3.

Discuss differences in healing patterns in the older patient.

- 4.

Describe complications presented by the medically compromised older patient.

- 5.

Describe each step of the process of diagnosis and treatment planning in the elderly patient.

- 6.

Identify factors that complicate case selection.

- 7.

Discuss why there are differences and what those differences are when root canal treatment is performed in the older patient.

- 8.

Recognize the complications of endodontic surgery.

- 9.

Select the appropriate restoration after root canal treatment.

- 10.

Identify those elderly patients who should be considered for referral.

Endodontic considerations in the elderly patient are similar in many ways to those in the younger patient, but there are some notable differences. This chapter discusses the similarities and concentrates on the differences. The topics include the biologic aspects of pulpal and periapical tissues, healing patterns, diagnosis, and treatment aspects in the geriatric patient.

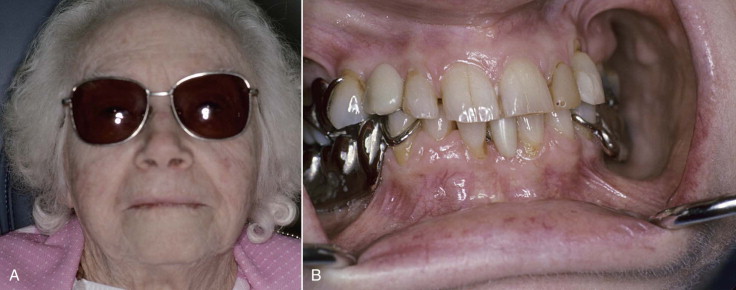

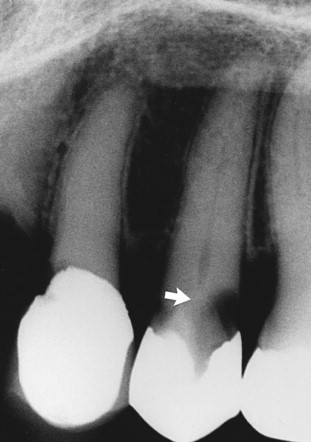

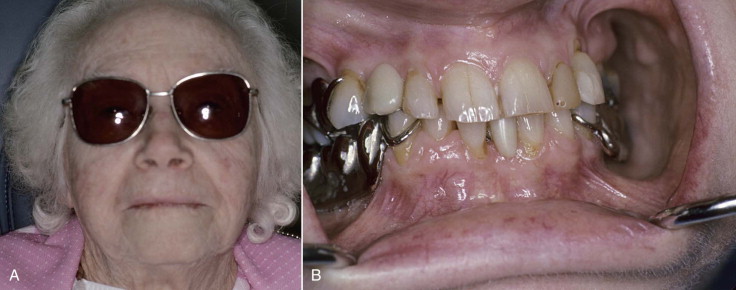

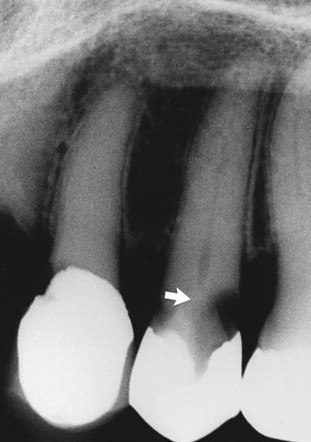

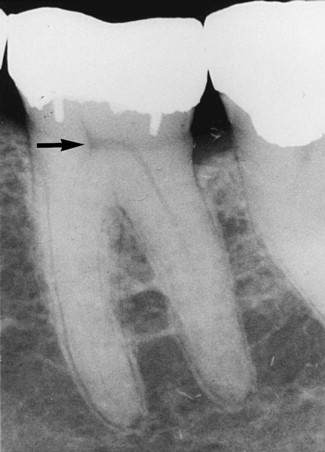

The number of persons aged 65 or older in the United States exceeds 39 million, and they are expected to comprise 20% of the population by 2020. Their dental needs will also continue to increase. More elderly patients will not accept tooth extraction unless there are no alternatives. They have a high utilization rate of dental services. The expectations for dental health parallel their demands for quality medical care. An even more important consideration is that these dentitions will continue to experience caries and decades of dental disease, in addition to restorative and periodontal procedures ( Fig. 25.1 ). These all have compound adverse effects on the pulp and periapical and surrounding tissues ( Fig. 25.2 ). In other words, the more injuries inflicted, the greater the likelihood of irreversible disease and thus the greater the need for treatment. The number of elderly endodontic patients is increasing and will continue to do so.

The combination of an increase in pathosis and dental needs, coupled with greater expectations, has resulted in more endodontic procedures among aging patients ( Fig. 25.3 ). Furthermore, expanded dental insurance benefits for retirees and more disposable income have made complex treatment more affordable. Other means will likely be available to finance the costs of oral health care in the future.

Endodontic considerations in elderly patients include biologic, medical, and some psychologic differences from younger patients, in addition to treatment complications. These considerations are further discussed in this chapter.

Learning Objectives

After reading this chapter, the student should be able to:

- 1.

Identify biologic aspects in the elderly patient that are similar to and different from those in the younger patient.

- 2.

Discuss age changes in the older dental pulp, both physiologic and anatomic.

- 3.

Discuss differences in healing patterns in the older patient.

- 4.

Describe complications presented by the medically compromised older patient.

- 5.

Describe each step of the process of diagnosis and treatment planning in the elderly patient.

- 6.

Identify factors that complicate case selection.

- 7.

Discuss why there are differences and what those differences are when root canal treatment is performed in the older patient.

- 8.

Recognize the complications of endodontic surgery.

- 9.

Select the appropriate restoration after root canal treatment.

- 10.

Identify those elderly patients who should be considered for referral.

Endodontic considerations in the elderly patient are similar in many ways to those in the younger patient, but there are some notable differences. This chapter discusses the similarities and concentrates on the differences. The topics include the biologic aspects of pulpal and periapical tissues, healing patterns, diagnosis, and treatment aspects in the geriatric patient.

The number of persons aged 65 or older in the United States exceeds 39 million, and they are expected to comprise 20% of the population by 2020. Their dental needs will also continue to increase. More elderly patients will not accept tooth extraction unless there are no alternatives. They have a high utilization rate of dental services. The expectations for dental health parallel their demands for quality medical care. An even more important consideration is that these dentitions will continue to experience caries and decades of dental disease, in addition to restorative and periodontal procedures ( Fig. 25.1 ). These all have compound adverse effects on the pulp and periapical and surrounding tissues ( Fig. 25.2 ). In other words, the more injuries inflicted, the greater the likelihood of irreversible disease and thus the greater the need for treatment. The number of elderly endodontic patients is increasing and will continue to do so.

The combination of an increase in pathosis and dental needs, coupled with greater expectations, has resulted in more endodontic procedures among aging patients ( Fig. 25.3 ). Furthermore, expanded dental insurance benefits for retirees and more disposable income have made complex treatment more affordable. Other means will likely be available to finance the costs of oral health care in the future.

Endodontic considerations in elderly patients include biologic, medical, and some psychologic differences from younger patients, in addition to treatment complications. These considerations are further discussed in this chapter.

Biologic Considerations

Biologic considerations are both systemic and local. The wide variety of systemic changes related to the patient’s medical status are covered in other textbooks. In the older patient, systemic or local changes unique to endodontics are no different from those for other dental procedures. Similarly, the response of the pulp and periapical tissues is not markedly different.

Pulp Response

Changes with Age

Two considerations are important in age-related changes in pulp response: (1) structural (histologic) changes that take place as a function of time and (2) tissue changes that occur in response to irritation from injury. These tend to have similar appearances in the pulp. In other words, injury may prematurely “age” a pulp. Therefore, an “old” pulp may be found in a tooth of a younger person (e.g., a tooth that has experienced caries, restorations, and so on). Whatever the etiology, these older (or injured) pulps react somewhat differently than do younger (or uninjured) pulps.

Chronologic Versus Physiologic

Does a pulp in an older individual react differently from an injured pulp in a younger individual? This question has not been answered definitively. Probably a previously injured pulp (from caries, restoration, and so on) in a younger person has less resistance to injury than an undamaged pulp in an older individual. At a histologic level, there are some consistent changes in these older pulps and in irritated pulps.

Structural

The pulp is a dynamic connective tissue. With age there are changes in cellular, extracellular, and supportive elements (see Chapter 1 ). There is a decrease in cells, including both odontoblasts and fibroblasts. There are also fewer supportive elements (i.e., blood vessels and nerves). Fewer and smaller vessels result in a decrease in blood flow in the pulp ; the significance of this decrease is unknown. Capillaries show somewhat degenerative changes in the endothelium with age. There is presumably an increase in the percentage of space occupied by collagen but less ground substance.

Calcifications

Calcifications include denticles (pulp stones) and diffuse (linear) calcifications. These increase in the aged pulp and in the irritated pulp. Pulp stones tend to be found in the coronal pulp, and diffuse calcifications are found in the radicular pulp. It has been speculated that the nidi of calcification arise from degenerated nerves or blood vessels, but this has not been proved. Another common speculation is that pulp stones may cause odontogenic pain; however, this is not true.

Dimensional

In general, pulp spaces progressively decrease in size and often become very small, a phenomenon known as calcific metamorphosis. Dentin formation may be accelerated by irritation from caries, restorations, and periodontal disease and is not uniform. For example, in molar pulp chambers there is more dentin formation on the roof and floor than on the walls. The result is a flattened (disklike) chamber ( Fig. 25.4 ).

Nature of Response to Injury

The older patient does tend to have more severe pulpal reactions to irritation than the reactions that occur in the younger patient. The reason for these differences is not fully understood, but they probably result from a lifetime of cumulative injuries.

From Irritation

There are reasons for pulp pathosis after restorative procedures. First, the tooth may have experienced several injuries in the past. Second, the tooth is likely to have undergone more extensive procedures that involve considerable tooth structure, such as crown preparation. Multiple potential injuries are associated with a full crown, such as foundation placement, bur preparation, impressions, temporary crown placement (often these leak), cementation, and unsealed crown margins. The coup de grâce of a pulp that is already stumbling along may be that final restoration.

Age

The aging pulp may be less resistant to injury, although this has not been proven. Pulp responses to various procedures in different age groups have not shown differences, although the large number of variables in these types of clinical studies make it difficult to isolate age as a factor. This is not necessarily the case with the immature tooth (open apex) in which pulps have indeed been shown to be more resistant to injury. There is a theory that pulps in older teeth may in fact be more resistant because of decreased permeability of dentin. Again, this resistance to injury in old teeth has not been proved. The bottom line is that older pulps in older patients require more care in preparation and restoration; this is probably the result of a history of previous insults rather than age per se.

Systemic Conditions

There is no conclusive evidence that systemic or medical conditions directly affect (decrease) pulp resistance to injury. One proposed condition is atherosclerosis, which has been presumed to directly affect pulp vessels ; however, the phenomenon of pulpal atherosclerosis could not be demonstrated.

Periapical Response

Little information is available on changes in bone and soft tissues with age and how these might affect the response to irritants or to subsequent healing after removal of those irritants. There is some indication that relatively little change occurs in periapical cellularity, vascularity, or nerve supply with aging. Therefore, it is unlikely that there are significantly different periapical responses in older patients compared with younger individuals.

Healing

A popular concept is that healing in older individuals is impaired, compromised, or delayed. This is not necessarily true. Studies in animals have shown remarkably similar patterns of repair of oral tissues in the young and the old, but with a slight delay in the healing response in the latter. Radiographic evidence of healing in younger and older patients after root canal treatment demonstrated no apparent difference in success and failure. No evidence exists that vascular or connective tissue changes in older individuals result in significantly slower or impaired healing. Overall, there is little difference in the nature of healing between the age groups, including healing of both bone and soft tissue. Vascularity is critical to healing, and in healthy individuals, periapical blood flow is not impaired with age.

Medically Compromised Patients

Certainly, systemic problems tend to occur in the older patient more often and with greater severity. In general, medical conditions are no more significant for endodontic procedures in the older patient than for other types of dental treatment. In fact, there is little information on the relationship of medical conditions or medically compromised status to adverse reactions during or after endodontic procedures.

Some conditions tend to be more common in older patients and require particular consideration. These include hypertension, cardiovascular disease, osteoporosis (often accompanied by bisphosphonate administration) and joint prostheses. A recent controversy is whether to administer prophylactic antibiotics prior to dental procedures in patients with joint prostheses. A recent Medicare Current Beneficiary Survey indicated that antibiotics are not indicated.

Both type I and type II diabetes make healing less predictable, although this is true at any age. There is particular concern about the person with severe, uncontrolled diabetes, who may require additional precautions and careful monitoring.

Another common condition is hypertension. Contrary to popular belief, using epinephrine in local anesthetics in hypertensive patients carries a very low risk of adverse effects.

Evidence exists that osteoporosis, a rather common condition of postmenopausal women, is associated with a decrease in trabecular bone density in the jaws, particularly in the anterior maxilla and the posterior mandible. However, it is not known whether patients with osteoporosis have impaired bony healing after root canal treatment or surgery. As related to diagnosis of periapical pathosis, osteoporotic changes are probably not of sufficient magnitude to confuse pretreatment or post-treatment evaluation. Interestingly, analysis of optical density from periapical radiographs from the posterior mandible is an indicator of osteoporotic changes in the lumbar and femoral regions in the elderly. Other considerations and the impact of bisphosphonate drug therapy, which is a co-factor in osteonecrosis of the jaws, are reviewed in Chapter 5 .

Anticoagulant therapy is common and tends to increase with age. These drugs are not a concern with conventional endodontic procedures. They are a consideration with surgery; there is ample opportunity for hemorrhage from both soft tissue and bone. The general recommendation is that anticoagulants not be altered before, during, or after these surgeries.

In summary, elderly medically compromised patients are generally at no more risk for complications than are other age groups. In fact, for a medically compromised patient, root canal treatment or other endodontic procedures are far less traumatic and damaging than extraction. A good example is the patient taking (or having taken) bisphosphonates. Root canal treatment and restoration are preferred to avoid the trauma of extraction.

Another important consideration is that older patients are more likely to be taking more and stronger medications. Caution is required to avoid interactions, particularly when prescribing additional medications.

Diagnosis

The same basic principles and diagnostic approaches apply for older patients as for younger ones. A difference is seen in the presence and level of responses.

Diagnostic Procedure

A routine sequence is applied to diagnosis, particularly with elderly patients. The most important findings are from the subjective examination to determine symptoms and the history. Careful questioning and allowing sufficient time for the older patient to recall and answer often yield valuable information.

Chief Complaint

The patient must be allowed to express the problem or problems in his or her own words. Not only does this divulge symptoms, but it also provides an opportunity to determine the patient’s dental knowledge and ability to communicate. This ability may be impaired because of problems with sight, hearing, or mental status.

Medical History

The prudent diagnostician not only discusses positive responses marked on the medical history form, but also repeats important items that may not have been marked or were overlooked by the patient. Systemic conditions, medications, and related considerations should be discussed in depth. It is appropriate at this time to explain how medical conditions might affect diagnosis, treatment planning, treatment, and outcomes.

Dental History

In general, elderly patients have a lot of history to review and recall. Important dental occurrences may be only a dim memory and require prompting by the examiner. Examples include a history of traumatic injury, fractures, caries, or pain and swelling.

Subjective Findings

Subjective findings include information obtained by questioning the patient’s description of current signs and symptoms. Many older patients are stoic, do not readily express adverse symptoms, and may consider them to be minor relative to other systemic problems or pains. A careful, concerned discussion about these seemingly minor problems also helps establish rapport and confidence.

Overall, symptoms of pulpitis are not as acute in the older patient. One reason may be that there is a reduced pulp volume and a decrease in sensory nerves, particularly in dentin.

The ab s ence of significant signs and symptoms is also very common, more so than their presence

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses