A frontal sinus fracture is a unique facial fracture that often requires complex management. The location of the frontal bone, which contains the frontal sinus, is adjacent to vital structures, including the brain and eyes. A frontal bone fracture often occurs concomitantly with fractures of the skull, orbital roof, and nose, and many times it is associated with Le Fort and naso-orbito-ethmoid (NOE) fractures. In addition, management of a frontal sinus fracture is complicated by the presence of concomitant injuries, mucosal membranes, and the nasofrontal ducts. Evaluation of a patient with a frontal sinus fracture is similar to that for other facial fractures and involves clinical assessment, radiographic evaluation, and formulation of a treatment plan that allows appropriate management. Treatment of a frontal sinus fracture varies greatly because of variations in the fracture pattern. Minimally displaced anterior table fractures are straightforward and treatment is easily accomplished with an open or endoscopic approach. However, the most severely comminuted anterior and posterior fractures often require neurosurgical intervention, cranialization, sinus obliteration, obstruction of the nasofrontal ducts, and reconstruction of the anterior table. In addition to surgical management, follow-up care for patients sustaining a frontal sinus fracture is prolonged and critical. Complications, including osteomyelitis, mucocele, and mucopyocele formation, can cause severe discomfort for the patient and in the most severe state can lead to brain abscess and death. Meticulous preoperative and intraoperative evaluation will lead to accurate assessment of a frontal bone fracture, which will then subsequently lead to the appropriate treatment plan for the patient. Execution of management then becomes critical for the long-term health of the patient and reduction of complications.

Anatomy

The anatomy of the frontal sinus is one of the most variable in the maxillofacial complex. The frontal sinus is a set of paired cavities in the frontal bone that communicate with the nasal cavity. Frontal sinuses are absent at birth, become well developed by age 6, and reach full size around 12 to 16 years, when they develop as the superior extension of the anterior ethmoidal sinus. Approximately 4% of the general population has absent frontal sinuses, and the left and right aspects of the frontal sinus are usually asymmetric. The frontal sinus is generally separated by a bony septum and drains into the hiatus semilunaris of the middle meatus via the nasofrontal ducts. The presence of a well-defined nasofrontal duct is also variable, with an incidence limited to 15%, whereas in the remaining population the sinus drains via a large hole emptying into the frontal recess. The typical size of a frontal sinus is 3.5 × 2.5 × 1.5 cm, with significant variation. The floor of the frontal sinus forms the orbital roof, whereas the posterior wall separates the anterior cranial fossa from the sinus. The arterial blood supply to the sinus is provided by the supraorbital arteries off the ophthalmic artery and the anterior ethmoidal arteries. Venous drainage is derived from the arterial counterparts, with additional drainage provided by the diploic veins and sagittal sinus. Sensation to the forehead area is provided by the trigeminal nerve, specifically the supraorbital and supratrochlear nerves off the ophthalmic nerve. The supraorbital nerve supplies sensation to the skin from the forehead extending back to the lambdoidal suture of the scalp and the conjunctiva. The epithelial lining of the frontal sinus is consistent with respiratory epithelium. It is composed of pseudostratified ciliated and columnar epithelium with interspersed goblet cells. The mucin produced by goblet cells is effectively cleared by ciliary flow through the nasofrontal ducts.

Epidemiology

A frontal sinus fracture is a facial fracture that occurs mostly in adults. Although the frontal sinus begins development in utero and undergoes a secondary phase of pneumatization between 6 months and 2 years, it is not identifiable on radiographs until the age of 6. The fact that frontal sinus fractures seldom occur in children and adolescents is consistent with this pattern of development. In the general population, the leading cause of a frontal sinus fracture is blunt trauma, with the majority occurring as a result of motor vehicle crashes. When considering that the frontal bone can sustain between 800 and 2200 lb of force, it is understandable that the incidence of frontal sinus fractures is lower than that of other facial fractures. Frontal sinus fractures account for 5% to 15% of all facial fractures, and a third to half of all frontal sinus fractures are associated with other facial fractures, including orbital and NOE fractures. Males sustain the majority of frontal sinus fractures, between 66% and 91%, and the peak age is between 20 and 30 years. Of frontal sinus fractures, 43% to 61% had isolated anterior table involvement, 0.6% to 6% had isolated posterior table involvement, 19% to 51% had a combination of anterior and posterior involvement, and 2.5% to 25% had damage to the nasofrontal ducts.

Epidemiology

A frontal sinus fracture is a facial fracture that occurs mostly in adults. Although the frontal sinus begins development in utero and undergoes a secondary phase of pneumatization between 6 months and 2 years, it is not identifiable on radiographs until the age of 6. The fact that frontal sinus fractures seldom occur in children and adolescents is consistent with this pattern of development. In the general population, the leading cause of a frontal sinus fracture is blunt trauma, with the majority occurring as a result of motor vehicle crashes. When considering that the frontal bone can sustain between 800 and 2200 lb of force, it is understandable that the incidence of frontal sinus fractures is lower than that of other facial fractures. Frontal sinus fractures account for 5% to 15% of all facial fractures, and a third to half of all frontal sinus fractures are associated with other facial fractures, including orbital and NOE fractures. Males sustain the majority of frontal sinus fractures, between 66% and 91%, and the peak age is between 20 and 30 years. Of frontal sinus fractures, 43% to 61% had isolated anterior table involvement, 0.6% to 6% had isolated posterior table involvement, 19% to 51% had a combination of anterior and posterior involvement, and 2.5% to 25% had damage to the nasofrontal ducts.

Evaluation of the Frontal Sinus

The three components involved in frontal sinus management include the anterior table, posterior table, and nasofrontal ducts. Each component requires individual attention and can alter the extent of intervention required. Management begins with clinical examination and follows with radiographic evaluation. The clinical manifestations of a frontal sinus fracture vary greatly depending on its severity; however, the mechanisms of trauma, particularly motor vehicle crashes, warrant thorough evaluation of the facial skeleton. In any patient with altered mental status, an evaluation for possible skull fractures must be performed. Any lacerations, contusions, edema, and frontal or periorbital ecchymosis may be suggestive of frontal sinus injury. Additionally, if there is crepitus in the frontal, supraorbital, or nasofrontal areas, attention must be focused on the possibility of frontal sinus or nasofrontal duct injury. Finally, any patient with the aforementioned clinical findings should be evaluated for possible cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) leakage secondary to fractures of the posterior table of the frontal sinus, cribriform plate, or fovea ethmoidalis. CSF leakage has been documented to occur in as many as a third of all frontal sinus injuries. The diagnosis of the CSF leakage can be made clinically by the ring test, or any fluid suggestive of CSF can be sent for analysis. In general, CSF fluid will have a higher concentration of chloride and a lower concentration of sodium than found in serum. However, the two most reliable tests for diagnosing CSF are beta 2 -transferrin and beta-trace proteins. Beta 2 -transferrin is a protein produced by neuraminidase activity in the brain, which is found only in CSF and perilymph. Beta-trace protein has higher predictive value, and the CSF-to-serum ratio of beta-trace protein is the highest of all CSF-specific proteins. Therefore, any fluid with the presence of beta 2 -transferrin or beta-trace protein is confirmatory of the presence of CSF.

The clinical examination must also include a neurologic examination because of the disproportionately high incidence of neurologic injury (50%) occurring concomitantly with a frontal sinus fracture. Finally, ocular examination is necessary because of the proximity of the globe to the affected bone and the 25% incidence of ophthalmologic injury occurring concurrently with frontal sinus fractures.

Once the clinical examination is completed, a radiographic examination is diagnostic for injuries to the frontal sinus and any other fractures often associated with the frontal sinus fracture. In past literature, authors have discussed the use of plain films; however, at the present time, any patient who sustains severe maxillofacial trauma will undergo non–contrast-enhanced facial computed tomography (CT). Facial CT is currently the most versatile diagnostic tool used to confirm the presence of a frontal sinus fracture. In addition, the severity of the fracture, concomitant fractures adjacent to the frontal sinus injury, and the presence of any foreign bodies can be evaluated effectively with CT.

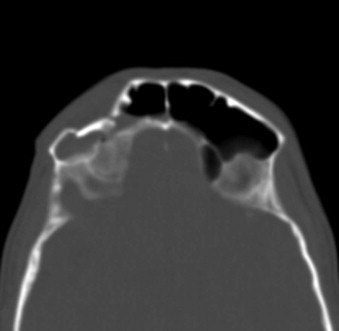

The anterior table is more susceptible to fracture because of its anterior position. However, its cortex is far thicker than that of the posterior table, and it represents one of the horizontal buttresses of the maxillofacial complex. The general rule for management is well documented and states that any fracture of the anterior cortex greater than one cortex width requires intervention. The rationale behind the one cortex width involves the resultant cosmetic deformity that develops because of displacement of the bone in a very conspicuous position on the face. Minimally displaced, isolated anterior table fractures do not usually cause any functional deficiencies. Anterior table fractures can occur in isolation or can extend from a concomitant NOE fracture or a Le Fort II or III fracture. Management of an anterior table fracture with regard to access, reduction, and fixation varies depending on its severity. For a minimally displaced anterior table fracture, conservative endoscopic management for reduction or recontouring has been reported. If the anterior table fracture is severely comminuted or open, direct access to the bone is required ( Fig. 43-1 ). Once generous access is established, visual assessment of the frontal sinus and evaluation of the nasofrontal duct can be performed. If the nasofrontal ducts are patent, the surgeon may proceed with the appropriate reduction and fixation of the anterior table fracture.

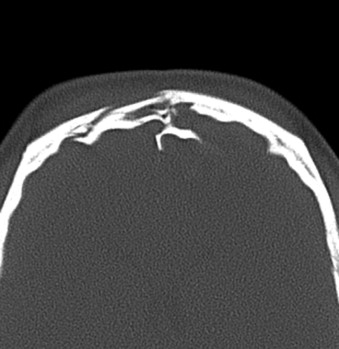

The second component of a frontal sinus fracture is the posterior table. The posterior table is thinner and provides less support; however, when fractured, it can lead to much more significant consequences. With the brain being directly adjacent to the posterior table, any force great enough to fracture the posterior table may lead to intracranial injury, including intracranial hematomas, contusions, dural tears, and a subsequent rise in intracranial pressure. The incidence of isolated posterior table involvement in a frontal sinus fracture is exceedingly rare, but when it occurs in combination with involvement of the anterior table, the incidence of intracranial injury and nasofrontal duct injury and the need for neurosurgical intervention increase significantly ( Fig. 43-2 ). If the situation dictates, neurosurgical intervention is the highest priority for maintenance of the patient’s life. Unlike isolated anterior table fractures, when the posterior table or the nasofrontal ducts are compromised, far more extensive surgical intervention is required. In the case of posterior table involvement in frontal sinus fractures, the determinant used for surgical intervention does not involve the displacement of a single cortical width, as for the anterior table. Reduction or débridement of a posterior table fracture is more influenced by neurosurgical need. If the patient has a significant dural tear with a persistent CSF leak, intracranial hemorrhage that necessitates evacuation, brain contusion with associated cerebral edema, and elevated intracranial pressure, craniotomy will be required to manage the injury to the brain. This obligates removal of the posterior table, obliteration of the frontal sinus, and obliteration of the nasofrontal ducts.

The third component of a frontal sinus fracture is the nasofrontal duct. The frontal sinus, similar to other paranasal sinuses, is functional and has a lining of ciliated columnar epithelium. The ciliated epithelium is responsible for evacuation of the mucus produced by the goblet cells distributed within the epithelium. The mucosa of the frontal sinus is continuous with the ethmoidal air cells and the nasofrontal ducts. Cilia transport the mucus in a clockwise fashion through the frontal sinus, nasofrontal ducts, and hiatus semilunaris and eventually into the nose. In the event that a patient’s nasofrontal ducts are damaged, the mucus that is produced and circulated has no means of evacuation. In addition, with damage to the epithelium secondary to the fracture, drainage from goblet cells is also compromised and leads to potential mucocele or mucopyocele formation. When drainage of the nasofrontal ducts is compromised, the surgeon is obligated to open the frontal sinus and proceed with obstruction of the ducts and sinus. Nasofrontal duct patency is not usually affected by minimally displaced anterior table fractures. The most common cause of nasofrontal duct damage is concomitant injuries, including NOE and Le Fort fractures of the maxilla ( Fig. 43-3 ). The nasal, ethmoid, lacrimal, maxillary, and frontal bones become comminuted and tear the sinus membrane and ductal epithelium, thereby obstructing the passage of mucus from the frontal sinus to the nose.

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses