Conditions requiring orthodontic treatment and replacement of missing teeth in young patients are by their very nature complex. The treatment approach must be multidisciplinary, requiring the close cooperation of a triad of prosthodontist, orthodontist, and oral and maxillofacial surgeon.

The advantage of absolute anchorage provided by an ankylosed dental implant was recognized by orthodontists early in the years following the advent of osseointegration. In more recent years, microimplants have enjoyed a certain level of popularity due to their novelty and ease of placement, however, their acceptance is waning somewhat with the realization by practitioners that they have a high failure rate. Intraosseous screws and bone plates offer the opportunity for secure orthodontic anchorage, although they are obviously more invasive. Dental implants used to obtain orthodontic anchorage have the advantage of being useable as part of the final prosthodontic restoration if the treatment has been properly planned and executed.

Dental implants intended to provide orthodontic anchorage can be placed either in an extra-alveolar location, outside of the tooth-bearing parts of the jaws, or in an intra-alveolar location within. This distinction is an important one as it pertains to growth of the young patient.

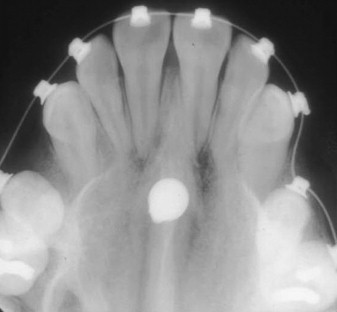

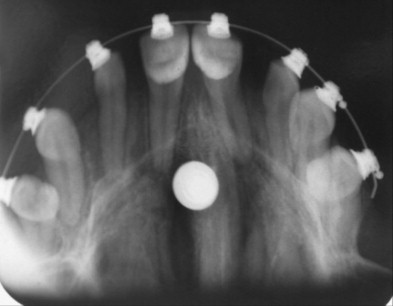

Extra-alveolar fixtures can be placed in the palate ( Fig. 1 ), the tuberosities of the maxilla, the zygomatic arches, or the retromolar areas of the mandible ( Fig. 2 ). These fixtures can be placed in growing children because they are temporary and may be removed after the conclusion of the orthodontic treatment. Such implants are particularly useful in patients with oligodontia who have significantly reduced dental anchorage options due to their missing teeth.

Intra-alveolar implant fixtures require careful planning. They are generally placed after skeletal maturity because they would otherwise interfere with alveolar development. Once placed, the position of these implants is final, and the orthodontist and prosthodontist must prescribe their locations with adequate forethought.

The normal treatment sequence in patients requiring multidisciplinary therapy begins with orthodontic idealization of the alignment of the teeth, implant placement, and, finally, prosthodontic treatment. When implants are needed to provide anchorage consideration must be given to the length of time required to achieve osseointegration so as not to interupt timely delivery of orthodontic treatment. The issue of wait time for osseointegration to take place is, however, becoming less important with the commercial availability of biologically active, more rapidly integrating implant surfaces.

Midpalatal anchorage

Midpalatal fixtures can provide absolute anchorage, and are particularly useful in patients who have deficient anchorage secondary to oligodontia ( Fig. 3 ), or as a means to facilitate distalization of posterior teeth as an alternative to conventional head gear therapy. These screws can be inserted easily under local anesthesia or with sedation. In growing children whose midpalatal sutures have not yet fused, the midpalatal sutures can be placed in a paramedian rather than a midline position.

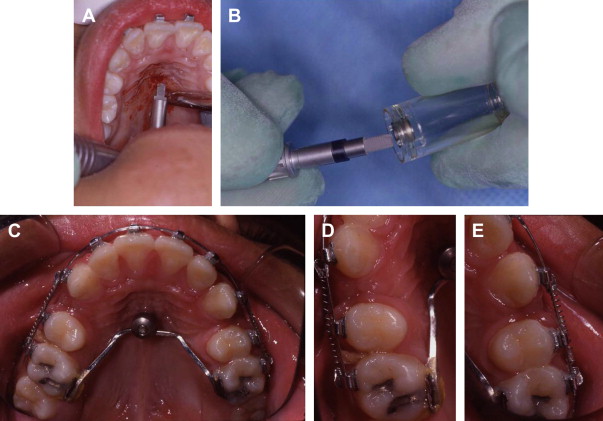

The midpalatal implant insertion begins with the removal of a mucosal plug using a punch mounted on a hand piece. The midline nasal crest of the maxilla is then drilled to the precise implant diameter ( Fig. 4 A). An implant ( Fig. 4 B) and a separate healing screw are then placed. Once osseointegration is complete, impressions are taken using a transfer coping, and a transpalatal bar is constructed in the laboratory that connects the implant fixture to the palatal surface of the teeth in the anchorage segment ( Fig. 4 C). Teeth can now be moved sequentially ( Fig. 4 D & E) or en masse. Once the orthodontic treatment is completed, the midpalatal implant can be removed.

Retromolar and tuberosity sites

Implants can be placed in the maxillary tuberosity or mandibular retromolar regions to obtain additional anchorage to help mesialize teeth or upright tipped mandibular molars. Once again, this technique may be particularly helpful in patients with oligodontia who have reduced anchorage. Placement of implants in these locations can be difficult: bone in the tuberosity may not be dense; and in the retromolar areas the rami may flare laterally dictating placement of the implant in a more buccal position than planned. Once healed, the implants can be temporarily restored with provisional crowns to facilitate bracket attachment and to open the bite if necessary ( Figs. 5 A– 5 B). Use of implant supported crowns in the posterior regions of the jaws to open the bite permits forced orthodontic eruption of the anterior dentition in order to achieve a definitive increase in the vertical dimension of occlusion. This increase can be particularly helpful in oligodontia where the vertical dimension of occlusion may be deficient to begin with. Once the planned tooth positions have been achieved ( Fig. 2 ), the remaining posterior dentition can be restored with dental implants\placed in ideal positions in the tooth-bearing portions of the alveolar processes ( Fig. 5 C).