Evidence-based dentistry is rapidly emerging to become an integral part of patient care, dental education, and research. Prosthodontics is a unique dental specialty that encompasses art, philosophy, and science and includes reversible and irreversible treatments. It not only affords good applicability of many principles of evidence-based dentistry but also poses numerous limitations. This article describes the epidemiologic background, fundamental considerations, scrutiny of levels of evidence, limitations, guidelines, and future perspectives of evidence-based prosthodontics. Understanding these principles can aid clinicians in appropriate appraisal of the prosthodontics literature and use the best available evidence for making confident clinical decisions and optimizing patient care.

Key points

- •

Prosthodontics is a unique specialty that offers numerous advantages and disadvantages for application of principles of evidence-based dentistry (EBD).

- •

An important difference between medical and dental models of care is the level of control a patient has about how, when, and whether it is necessary to treat a dental problem. This is especially true in the discipline of prosthodontics. Hence, an absolute extrapolation of evidence-based concepts from medicine to prosthodontics is not possible.

- •

Current lack of “strong” evidence for a particular treatment does not necessarily imply that the treatment is “inferior” or “clinically ineffective.” Efforts should be targeted, however, to improve the future scientific evidence for such treatments.

- •

Due to the unique nature of prosthodontics, it is necessary to establish a consensus on guidelines for reporting prosthodontic outcomes. These guidelines can ensure that investigators provide standardized reporting of their studies in order for them to be clear, complete, and transparent and allow integration of their evidence into clinical practice.

- •

In order to teach and understand evidence-based prosthodontics, academicians and clinicians need to attain new skills pertaining to computer-based knowledge systems. These skills are necessary to use scientific evidence for the 5-step process of asking, acquiring, appraising, applying, and assessing.

- •

Evidence-based prosthodontics can change the future course of prosthodontics education, patient care, reimbursements, research agendas, and oral health policies that have an impact on prosthodontics.

Introduction

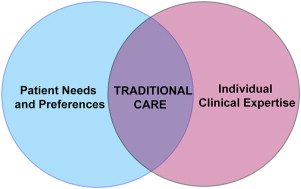

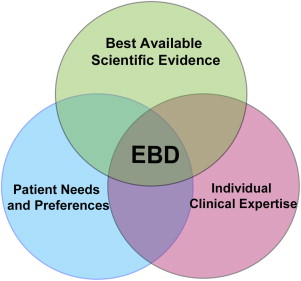

The traditional model of care in dentistry involves use of individual clinical expertise and patient treatment needs to provide dental care ( Fig. 1 ). This model of care has been used for centuries across the world and is primarily based on observations, beliefs, and personal and expert opinions. Although this model has not led to any devastating effects in dentistry, it precludes systematic assimilation, acceptance, and assessment of new treatment effects. Furthermore, it provides minimal confidence to clinicians for making clinical decisions for new scenarios and new treatments. The term, evidence-based practice , is defined as “the conscientious, explicit and judicious use of current best evidence in making decisions about the care of the individual patient. It means integrating individual clinical expertise with the best available external clinical evidence from systematic research.” This definition stems from the medical perspective, and dentistry is more familiar with the term, EBD.

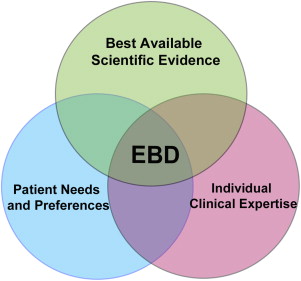

Currently, there is no definition for evidence-based prosthodontics but it is understood that it encompasses the application of EBD with respect to prosthodontics. According to the American Dental Association (ADA), EBD is defined as “an approach to oral healthcare that requires the judicious integration of systematic assessments of clinically relevant scientific evidence, relating to the patient’s oral and medical condition and history, with the dentist’s clinical expertise and the patient’s treatment needs and preferences.” Therefore, the EBD process is not a rigid methodologic evaluation of scientific evidence that dictates what practitioners should or should not do but also relies on the role of individual professional judgment and patient preference in this process ( Fig. 2 ).

Introduction

The traditional model of care in dentistry involves use of individual clinical expertise and patient treatment needs to provide dental care ( Fig. 1 ). This model of care has been used for centuries across the world and is primarily based on observations, beliefs, and personal and expert opinions. Although this model has not led to any devastating effects in dentistry, it precludes systematic assimilation, acceptance, and assessment of new treatment effects. Furthermore, it provides minimal confidence to clinicians for making clinical decisions for new scenarios and new treatments. The term, evidence-based practice , is defined as “the conscientious, explicit and judicious use of current best evidence in making decisions about the care of the individual patient. It means integrating individual clinical expertise with the best available external clinical evidence from systematic research.” This definition stems from the medical perspective, and dentistry is more familiar with the term, EBD.

Currently, there is no definition for evidence-based prosthodontics but it is understood that it encompasses the application of EBD with respect to prosthodontics. According to the American Dental Association (ADA), EBD is defined as “an approach to oral healthcare that requires the judicious integration of systematic assessments of clinically relevant scientific evidence, relating to the patient’s oral and medical condition and history, with the dentist’s clinical expertise and the patient’s treatment needs and preferences.” Therefore, the EBD process is not a rigid methodologic evaluation of scientific evidence that dictates what practitioners should or should not do but also relies on the role of individual professional judgment and patient preference in this process ( Fig. 2 ).

Need for evidence-based prosthodontics

With rapid advancements in dental materials and dental technology and improved understanding of clinical outcomes, a surfeit of research has been published in prosthodontics and dental implant–focused literature ( Box 1 ). Furthermore, a surplus amount of published research exists in interdisciplinary fields that are of critical importance to prosthodontics. It is well known that not all published literature is scientifically valid and clinically useful. Therefore, a critical analysis of the quality of published research and consolidation of the excess scientific information is necessary to render them significant and useful. In an extensive analysis of scientific publications between 1966 and 2005, Harwood noted that there were 44,338 published articles in prosthodontics. Of these, there were 955 randomized controlled clinical trials (RCTs) (2%). Nishimura and colleagues identified 10,258 articles on prosthodontic topics between 1990 and 1999 and estimated that to stay current in the year 2002 would require reading and absorbing approximately 8 articles per week, 52 weeks per year, and across 60 different journals. These numbers do not include published articles on implant dentistry. Russo and colleagues identified 4655 articles published between 1989 and 1999 dedicated to implant dentistry and estimated that to stay current in the year 2000 would require reading and absorbing approximately 1 to 2 articles per week, 52 weeks per year. It is not difficult to assume that these numbers are significantly higher in the year 2013 and will continue to grow due to increased growth in the number of journals and publications, underscoring the need for computer-based clinical knowledge systems and for clinicians to acquire new skills to use the best available scientific evidence (BASE) ( Box 2 ).

- •

Enable the recognition of best available scientific evidence in prosthodontics.

- •

Consolidate the scientific information overload in prosthodontics and related literature.

- •

Scrutinize the scientific basis for existing prosthodontic treatments.

- •

Improve current and future treatments.

- •

Encourage improvement in the quality of clinical research as well as in reporting.

- •

Distinguish and advance the specialty of prosthodontics.

- •

Asking the appropriate research question for a clinical situation of interest.

- •

Acquiring information through efficient scientific literature search.

- •

Appraising the acquired information.

- •

Applying the acquired information to clinical practice, along with individual clinical expertise and patient preferences.

- •

Assessing the results of the applied intervention to optimize the clinical situation.

Epidemiologic background

The epidemiologic background for evidence-based practice dates back to the nineteenth century, to the work of John Snow, who is widely regarded as the father of modern epidemiology. Snow rejected the popular miasma theory as the cause of the cholera outbreaks in England. Through a systematic method of data collection and analysis, Snow established a classic case-control study and traced the cholera outbreaks to drinking water contamination from the sewage systems. His ideas were rejected, criticized, and not embraced until several years after his death. Similar to Snow’s experiences, other landmark events in modern epidemiology include Semmelweis’ important discoveries on hand washing intervention to drop maternal mortality rates and childbed fever and Doll and colleagues’ systematic observations on cigarette smoking and its association with lung cancer. Several other similar events have all had a significant impact on worldwide public health.

Pioneering efforts in the twentieth century by Archibald Cochrane called for state-of-the-art systematic reviews (SRs) of all relevant RCTs in health care, leading to the creation of the world-renowned Cochrane Collaboration in 1993 to organize all medical research information in a systematic manner in the interests of evidence-based medicine. The term, evidence-based medicine, itself was first described in the medical literature in 1992 by a working group of a similar name, who stated that this would be a new way of teaching the practice of medicine. The ADA has espoused the principles of evidence-based practices since its inception and has made remarkable progress over the past 20 years to render popularity to the current known principles of EBD for use in clinical practice and dental education.

Considerations in prosthodontics

An important difference between medical and dental models of care is the level of control a patient has about how, when, and whether it is even necessary to treat a dental condition. This is especially true in the discipline of prosthodontics. Prosthodontics is a unique dental specialty that encompasses art, philosophy, and science and includes reversible and irreversible treatments. Therefore, an absolute extrapolation of evidence-based concepts from medicine to prosthodontics is not possible. Treatment outcomes, which are a core element of prosthodontics, however, render themselves well for application of principles of EBD. There are 3 predominant items that are important to understanding challenges in reporting treatment outcomes in prosthodontics.

Defining the Outcomes of Clinical Interest

Key issues in defining clinical outcomes in prosthodontics are multifaceted due to the inherent nature of the treatment. Some examples of these issues include differentiating success versus survival, complications versus consequences, and prosthesis outcomes versus patient-centered outcomes. Another important characteristic is defining the appropriate endpoint of a clinical study. Hujoel and DeRouen have categorized clinical endpoints (outcomes) as surrogate endpoints and true endpoints. Surrogate outcomes include measures that are not of direct practical importance but are believed to reflect outcomes that are important as part of a disease/treatment process. True outcomes, however, reflect unequivocal evidence of tangible benefit to patients. Both types of outcomes are important in prosthodontics, because surrogate outcomes are helpful for preliminary evidence and true outcomes are helpful for definitive evidence ( Table 1 ).

| Surrogate Outcomes | True/Definitive Outcomes |

|---|---|

| Includes measures that are not of direct practical importance but are believed to reflect outcomes that are important as part of a disease/treatment process | Reflects unequivocal evidence of tangible benefit to the patient |

|

|

| Endpoints are “softer” and easier to measure and studies are relatively inexpensive. | Endpoints are “harder” and difficult to measure and studies can be more expensive. |

| Do not have a direct impact on changes in clinical practice or changes in public health policies. | Can have a direct impact on changes in clinical practice and/or changes in public health policies. |

Duration Needed to Appropriately Study the Outcomes

The time period needed to study a clinical outcome of interest depends on the definition of a treatment outcome, surrogate or true endpoint desired, treatment effect desired, and adverse events related to a treatment under investigation. Currently, there is no consensus in prosthodontics on definitions for preliminary, short-term, or long-term studies. Therefore, it becomes the prerogative of the investigator, editor, and reader to decide if the result of a study reports on short-term or long-term outcomes. Often, a study with a follow-up period of up to 6 years is described as “long-term follow-up” where only a meager number of samples have actually made it to a 6-year follow-up and the rest have a follow-up of less than 2 years. It is understood that preliminary and short-term studies have high clinical impact when they report failures of a particular treatment; only long-term studies can have high clinical impact for treatment success. Treatment success reported in short-term studies, however, can lay the justification whether additional research is needed.

Minimum Sample Needed to Study the Outcome of Interest?

The sample size of a study depends on the difference in treatment effect desired. In prosthodontics, it is difficult to obtain large sample sizes from a single study center because of the elective and expensive nature of prosthodontic treatment, which has led to a large body of published research in the prosthodontic literature with small sample sizes. For a study to have a large clinical impact and provide sufficient evidence to change a particular clinical practice, sample size is critical. Currently, there is no consensus in prosthodontics on definitions for sample sizes as small, moderate, and large. The validity of defining such sample sizes is currently unknown.

Levels of evidence and prosthodontics

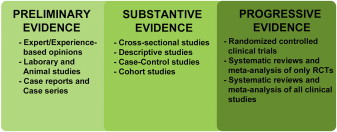

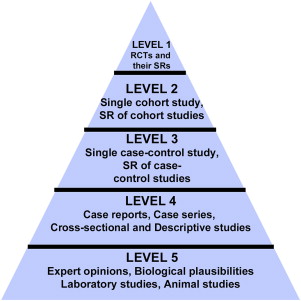

Evidence in medicine has been popularly categorized into 5 hierarchical levels and widely represented as a pyramid with the “weakest/lowest level of evidence” at the base and the “strongest or highest level evidence” at the apex ( Fig. 3 ). This gradation has been used by several health agencies across the world. Although the 5 hierarchical levels of evidence and the pyramidal representation may be popular in medicine, the applicability of this paradigm to prosthodontics is questionable because few articles in prosthodontics comprise RCTs and large cohort studies, implying that most current clinical practices in prosthodontics are all based on “weak evidence.”

Additionally, 2 critical elements of importance to prosthodontics that are omitted from the evidence-based pyramid are sample size and duration of a study. As previously discussed, these 2 elements can significantly affect the way evidence has an impact on clinical practices. For example, results from a cohort or a case-control study with a very large sample size and/or a long-term follow-up on all-ceramic crowns can have a better impact on clinical decisions compared with results from an RCT with a small sample and a short-term follow-up. In this scenario, in spite of RCT regarded as the “strongest evidence,” it would fail to be used by clinicians for confident decision making. Furthermore, major medical breakthroughs have originated from cohort and case-control studies, which are considered by many as “weaker” forms of evidence. The terms, weak and strong , are subjective and exclusive and do not lend themselves to an unbiased assessment of best available evidence in prosthodontics. Therefore, an alternative approach for prosthodontics literature is suggested. The suggested paradigm involves a horizontal spectrum encompassing 3 stages of evidence—preliminary evidence, substantive evidence, and progressive evidence ( Fig. 4 ).