This clinical article reports an esthetic treatment option for managing a Class II malocclusion in an adult. The patient, a woman aged 24 years 2 months, had crowding and a convex profile. She was treated with maxillary first premolar extractions, a double J retractor, and temporary skeletal anchorage devices in the maxillary arch. Posttreatment records after 2 years showed excellent results with good occlusion and long-term stability.

The correction of dental crowding is a common orthodontic treatment that can be performed with a removable or fixed appliance or a combination of both. Until recently, the process of straightening teeth has typically involved appliances including brackets, bands, and wires, but many adult patients are reluctant to wear fixed appliances. Consequently, the desire for a cosmetic solution for misaligned teeth has caused more patients to seek veneers, crowns, and other laboratory-fabricated cosmetic restorations.

Clear brackets can be placed for esthetic reasons, but they can irritate soft tissues because of their size. Lingual brackets might be a great alternative for those who desire straight teeth without visible brackets, but, although lingual orthodontic techniques have improved, they generally require more chair time and might not be cost-effective. Clear removable appliances have the benefits of improved oral hygiene and esthetics. These appliances have become increasingly popular among adults who want to straighten their teeth without using conventional brackets. However, in orthodontics, precisely controlled force application is required to achieve the final alignment.

The purpose of this article is to report the use of a modified type of lingual retractor, the double J retractor, and temporary skeletal anchorage devices for en-masse retraction of the 6 anterior teeth in a patient with premolar extractions.

Diagnosis and etiology

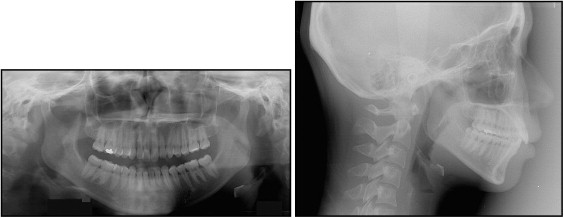

A woman aged 24 years 2 months was referred by a general dentist for evaluation of anterior crowding. Her chief complaint was the appearance of her maxillary anterior teeth and upper lip ( Fig 1 ). She did not want to have fixed orthodontic appliances in the maxillary arch because of their appearance, especially when smiling. She had a convex profile and a Class II skeletal pattern, with a Class II Division 1 malocclusion. Her facial form was mesocephalic, with good symmetry, a mildly increased lower facial height, and a retrognathic chin. Lip competence could be achieved but with some mentalis strain. There were no signs of temporomandibular joint dysfunction, and mandibular movements were normal, with no evidence of deviation. Intraorally, her maxillary and mandibular midlines were centered relative to her facial midline. All permanent teeth were present, and she had fair oral hygiene and probing depths within the norms. The patient was in good general health and had no history of major systemic diseases. She had no history of dental trauma or parafunctional habits, and the etiology of her occlusion was believed to be heredity.

Pretreatment records showed that the patient had an end-on Class II relationship on the right and the left at the first molars and canines. There was moderate crowding in the maxillary arch and mild crowding in the mandibular arch with a severe curve of Spee. She had a 6.3-mm overjet and an 80% overbite. The teeth were free of caries with no pathologies. The third molars were missing.

The cephalometric analysis indicated skeletal Class II (ANB, 8.4°; Wits, 3.6 mm) with a hyperdivergent growth pattern (SN-MP, 44.9°). The maxillary incisors were slightly retroclined (U1-SN, 96.2°) caused by bilateral rotation of the maxillary central incisors, and the mandibular incisors showed a slight retroclincation (IMPA, 88.3°) ( Fig 2 ; Table ).

| Measurement | Japanese norm | Pretreatment | Posttreatment | 2 years posttreatment |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SNA (°) | 82.0 | 83.5 | 82.1 | 79.9 |

| SNB (°) | 80.0 | 75.0 | 74.9 | 75.1 |

| ANB (°) | 2.0 | 8.4 | 7.2 | 4.8 |

| Wits (mm) | 1.1 | 3.6 | 4.7 | 2.7 |

| SN-MP (°) | 32.0 | 44.9 | 45.2 | 45.0 |

| FH-MP (°) | 25.0 | 35.0 | 35.9 | 35.3 |

| LFH (ANS-Me/N-Me) (%) | 55.0 | 57.1 | 57.4 | 57.3 |

| U1-SN (°) | 104.0 | 96.2 | 90.7 | 94.7 |

| U1-NA (°) | 22.0 | 12.8 | 8.5 | 14.8 |

| IMPA (°) | 90.0 | 88.3 | 91.7 | 88.3 |

| L1-NB (°) | 25.0 | 28.2 | 31.0 | 28.7 |

| U1/L1 (°) | 124.0 | 130.6 | 133.2 | 131.7 |

| Upper lip (mm) | 1.2 | 4.1 | 0.8 | 0.6 |

| Lower lip (mm) | 2.0 | 4.8 | 2.2 | 2.0 |

Treatment objectives and plan

The treatment objectives were to obtain normal overjet and overbite, establish Class I canine and molar relationships, relieve the crowding in both arches, level the curve of Spee, and improve the patient’s profile without the use of labial fixed appliances in the maxillary arch.

With temporary skeletal anchorage devices, distal movement of the anterior or posterior teeth or both, without anchorage loss, would be possible. This patient wanted to retract her upper lip as much as possible, so the maxillary first premolars were extracted, but, to camouflage the skeletal Class II pattern, the mandibular second premolars were not extracted.

Treatment objectives and plan

The treatment objectives were to obtain normal overjet and overbite, establish Class I canine and molar relationships, relieve the crowding in both arches, level the curve of Spee, and improve the patient’s profile without the use of labial fixed appliances in the maxillary arch.

With temporary skeletal anchorage devices, distal movement of the anterior or posterior teeth or both, without anchorage loss, would be possible. This patient wanted to retract her upper lip as much as possible, so the maxillary first premolars were extracted, but, to camouflage the skeletal Class II pattern, the mandibular second premolars were not extracted.

Treatment alternatives

With no growth modification possible, correction of the Class II molar relationship could be accomplished by nonextraction molar distalization treatment, extraction of the maxillary first premolars and the mandibular second premolars, or extraction of only the maxillary first premolars.

To accomplish the treatment objectives, conventional esthetic treatment options for the maxillary orthodontic appliances included lingual orthodontic appliances or clear removable appliances. However, a difficult problem to overcome in lingual orthodontics has been torque control of the anterior teeth. A potential disadvantage of clear removable appliances is that they highly depend on patient compliance. The other significant weakness is the aligner cannot move the root apex efficiently which results in the tipping of teeth especially in extraction cases. Compared with those 2 esthetic orthodontic appliances, the double J retractor offered an effective tool for producing translational tooth movement during anterior retraction; a treatment plan was developed that included extraction of the maxillary first premolars, delivery of the double J retractor, and use of temporary skeletal anchorage devices to achieve bodily translation.

Because of the skeletal discrepancies that resulted from an unfavorable growth pattern, bilateral sagittal split osteotomy was discussed for mandibular advancement combined with orthodontic treatment. Upon completion of the orthodontic treatment, genioplasty would be another option to improve her profile, but the patient declined all surgical options.

Treatment progress

Before orthodontic treatment, the patient was referred to an oral surgeon to extract her maxillary first premolars.

Because she had high esthetic demands and was unwilling to tolerate the extraction spaces, esthetic pontics were bonded to the distal aspects of the maxillary canines. The double J retractor is an alternative method for obtaining the desired direction of force on the maxillary anterior teeth. We used bonding pads instead of mesh brackets, which were common with earlier lingual retractors. The anterior lever arm hooks were bent in the wire approximately 20 mm from the pad so that the line of action of the force passed through the center of resistance. The posterior lever arm hooks were extended from the lingual crown surfaces of the canines. Both hooks can be used for space closing with elastic chains or superelastic closed-coil springs, and the posterior hooks can be used for torque control with Class II elastics. In this case, however, to minimize extrusion of the posterior mandibular teeth, the patient wore the Class II elastics at night only when it was necessary. After the retractor was adjusted to the lingual surface of the anterior teeth, it was bonded to them. Transbond (3M Unitek, Monrovia, Calif) was used, in addition to the customary bonding adhesive, to resist the shearing forces that occur when loading the retractor. Three temporary skeletal anchorage devices were placed (OSAS, Tuttlingen, Germany). Two (diameter, 1.6 mm; length, 8.0 mm) were placed palatally between the maxillary first and second molars, and 1 temporary anchorage device (diameter, 1.6 mm; length, 7.0 mm) was placed in the midpalate. Elastic chains or superelastic closed-coil springs were stretched from the anterior hooks to the temporary skeletal anchorage devices ( Fig 3 ).

A cephalometric film was used to determine the point of force application of the appliance with the aid of a gutta-percha cone as a radiopaque guide. Power elastic chains or nickel-titanium closed-coil springs that delivered 200 g per side provided the retraction force for space closure. In addition, the intrusion force of the lingual retractor was 60 g per side.

Biomechanically, the position of the hook in the lever arm wire can change the point of force application with respect to the center of resistance of the teeth to be intruded and retracted. During lingual retraction, the maxillary left posterior temporary skeletal anchorage device failed, so another (diameter, 1.6 mm; length, 8.0 mm; OSAS) was installed between the maxillary left second premolar and first molar. After 6 months, the anterior teeth were retracted so that only 1 to 1.5 mm of space remained between the canines and the second premolars. At this point, the patient was satisfied with the results, and she agreed to allow the fixed appliances be bonded for axial control and root movement. The 0.022 × 0.028-in edgewise ceramic brackets were bonded in both arches. After leveling, 0.018 × 0.025-in stainless steel wires were placed for the remaining space closure in the maxillary arch. At this point, the patient wanted to retract her upper lip a bit more. Because of her request during the space closure, the maxillary anterior teeth were slightly tipped lingually ( Fig 3 ).

In the mandibular arch, during the leveling stage, a sectional 0.016-in copper-nickel-titanium wire was used between the mandibular incisors to achieve their initial leveling. Then a mandibular utility archwire was constructed with 0.016 × 0.022-in stainless steel wire. With a mandibular utility archwire, intrusive forces were applied to the mandibular incisors labially to the center of resistance. It produced a labial crown moment that resulted in proclination of the mandibular incisors. To minimize this side effect, labial root torque was included in the incisor region of the mandibular utility archwire. To produce approximately 60 g of incisor intrusion force, 20° of distal molar crown tip was activated. To prevent the need for mandibular molar extrusion, buccal root torque and expansion were applied to the molars by establishing cortical anchorage. After leveling the mandibular arch, a flat 0.016 × 0.022-in nickel-titanium archwire was used. At the finishing stage, a mild curve of Spee in the maxillary archwire and a mild reverse curve of Spee in the mandibular archwire were placed by using 0.018 × 0.025-in stainless steel wires.

To establish acceptable overbite and overjet, intreproximal reduction was done on the mandibular anterior dentition during the finishing stage. A tooth positioner was used for final detailing. After treatment, the curve of Spee of the mandibular arch was found to be successfully leveled. Active treatment time was 18 months. For a better esthetic result, an advancement genioplasty could have been considered. After treatment, maxillary and mandibular Essix retainers (Dentsply Raintree Essix, Sarasota, Fla) were delivered. The patient was instructed to wear them 24 hours per day for 1 year and then at night only. Recall visits for retainer checks occurred at 1, 3, and 6 months during the first year. To ensure continued satisfactory posttreatment alignment of the mandibular and maxillary anterior dentition, the use of retainers was recommended indefinitely.

The detailed calculation method has already been described in previous articles.

For our patient, the double J retractor was constructed of a segmented archwire bonded to the 6 anterior teeth, and lever arms extended from the segmented archwire. Both were made of a stiff 0.028-in steel wire (Young’s modulus, 200 GPa), and forces were applied at the ends of the lever arm. Assuming symmetry on both sides of the arch, a model of only the left side was fabricated. A lateral view of the finite element model is shown in Figure 4 .