Learning Objectives

After reading this chapter, the student should be able to:

- 1.

Discuss the role of endodontic surgery in treatment planning for a patient.

- 2.

Recognize situations in which surgery is the treatment of choice.

- 3.

Recognize medical or dental situations in which endodontic surgery is contraindicated.

- 4.

Define the terms incision for drainage, apical curettage, root-end resection, root-end preparation and filling, root amputation, hemisection, and bicuspidization.

- 5.

Briefly describe the step-by-step procedures involved in periapical surgery, including those for incision and reflection, access to the apex, apical curettage, root-end resection, root-end preparation and filling, flap replacement, and suturing.

- 6.

Discuss the indications for each procedure listed in objective 4.

- 7.

Discuss the prognosis for each procedure listed in objective 4.

- 8.

State the principles of flap design.

- 9.

Diagram the various flap designs and describe the indications, advantages, and disadvantages of each.

- 10.

List the more common root-end filling materials.

- 11.

Review the basic principles of suturing.

- 12.

Describe general patterns of soft and hard tissue healing.

- 13.

Write out instructions to be given to the patient concerning postoperative care after endodontic surgery.

- 14.

List and describe conditions that indicate referral to a specialist for evaluation or treatment.

Nonsurgical root canal therapy is a highly successful procedure if diagnosis and technical aspects are carefully performed. There is a common belief that if root canal therapy fails, surgery is indicated for correction. This is not necessarily true; most failures are best corrected by retreatment (revision). Studies have shown that between 77% and 89% of retreated cases are successful after retreatment of the original root canal therapy. However, there are situations in which surgery is necessary to retain a tooth that would otherwise be extracted.

Endodontic surgery is not “oral surgery” in the traditional sense. Rather, it is actually “endodontic treatment through a surgical flap.” Simply cutting off the apex of a root and placing a filling in the vicinity of the canal does not accomplish the goals of endodontic surgical treatment. The purposes of endodontic surgery include sealing of all portals of exit from the root canal system and the isthmuses, eliminating bacteria and preventing their byproducts from contaminating the periradicular tissues, and providing an environment that allows for regeneration of periradicular tissues.

During the past decade, the art and science of endodontic surgery have changed dramatically. Endodontic surgery was previously limited to the anterior teeth, where access was considered adequate. With the introduction of the operating microscope, ultrasonic tips, and new root-end filling materials, teeth that might otherwise be extracted now have a chance for retention.

This chapter describes both the indications for and the procedures involved in incision for drainage, periapical surgery, and corrective surgical procedures, such as root amputation, hemisection, and bicuspidization.

Learning Objectives

After reading this chapter, the student should be able to:

- 1.

Discuss the role of endodontic surgery in treatment planning for a patient.

- 2.

Recognize situations in which surgery is the treatment of choice.

- 3.

Recognize medical or dental situations in which endodontic surgery is contraindicated.

- 4.

Define the terms incision for drainage, apical curettage, root-end resection, root-end preparation and filling, root amputation, hemisection, and bicuspidization.

- 5.

Briefly describe the step-by-step procedures involved in periapical surgery, including those for incision and reflection, access to the apex, apical curettage, root-end resection, root-end preparation and filling, flap replacement, and suturing.

- 6.

Discuss the indications for each procedure listed in objective 4.

- 7.

Discuss the prognosis for each procedure listed in objective 4.

- 8.

State the principles of flap design.

- 9.

Diagram the various flap designs and describe the indications, advantages, and disadvantages of each.

- 10.

List the more common root-end filling materials.

- 11.

Review the basic principles of suturing.

- 12.

Describe general patterns of soft and hard tissue healing.

- 13.

Write out instructions to be given to the patient concerning postoperative care after endodontic surgery.

- 14.

List and describe conditions that indicate referral to a specialist for evaluation or treatment.

Nonsurgical root canal therapy is a highly successful procedure if diagnosis and technical aspects are carefully performed. There is a common belief that if root canal therapy fails, surgery is indicated for correction. This is not necessarily true; most failures are best corrected by retreatment (revision). Studies have shown that between 77% and 89% of retreated cases are successful after retreatment of the original root canal therapy. However, there are situations in which surgery is necessary to retain a tooth that would otherwise be extracted.

Endodontic surgery is not “oral surgery” in the traditional sense. Rather, it is actually “endodontic treatment through a surgical flap.” Simply cutting off the apex of a root and placing a filling in the vicinity of the canal does not accomplish the goals of endodontic surgical treatment. The purposes of endodontic surgery include sealing of all portals of exit from the root canal system and the isthmuses, eliminating bacteria and preventing their byproducts from contaminating the periradicular tissues, and providing an environment that allows for regeneration of periradicular tissues.

During the past decade, the art and science of endodontic surgery have changed dramatically. Endodontic surgery was previously limited to the anterior teeth, where access was considered adequate. With the introduction of the operating microscope, ultrasonic tips, and new root-end filling materials, teeth that might otherwise be extracted now have a chance for retention.

This chapter describes both the indications for and the procedures involved in incision for drainage, periapical surgery, and corrective surgical procedures, such as root amputation, hemisection, and bicuspidization.

Incision for Drainage

The objective of incision for drainage is to evacuate inflammatory exudates and purulence from a soft tissue swelling. Incision for drainage reduces discomfort resulting from the buildup of pressure and speeds healing.

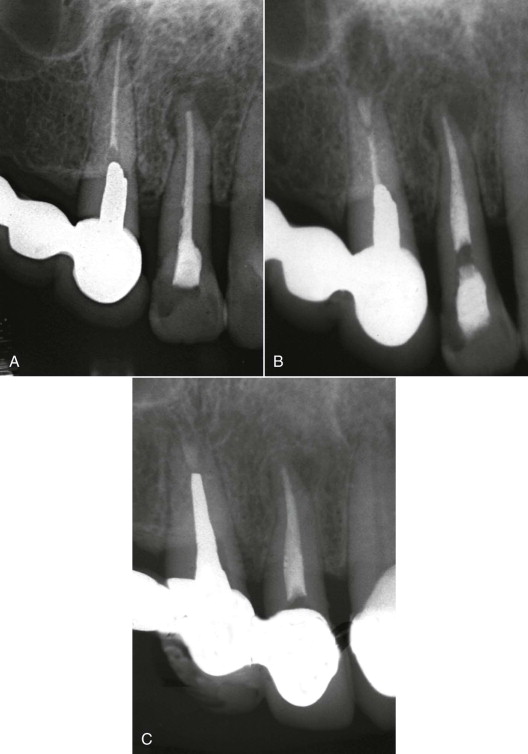

Indications

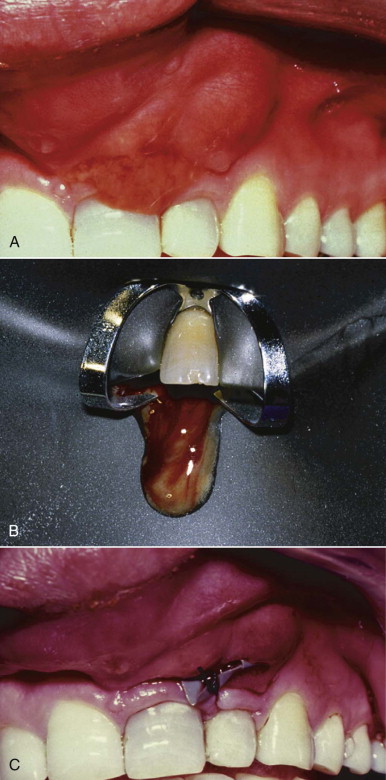

The best treatment for swelling originating from a symptomatic apical abscess of pulpal origin ( Fig. 21.1, A ) is to establish drainage through the offending tooth ( Fig. 21.1, B ). When adequate drainage cannot be accomplished through the tooth itself, drainage is obtained through soft tissue incision. Occasionally, drainage is performed through the soft tissue even if it has also been obtained through the tooth (see Fig. 10.3 B ; also Fig. 21.1, B, C ). The reason for this is that there may be separate, noncommunicating abscesses—one at the apex and another in a submucosal location or in an anatomic space.

Drainage through the soft tissue is accomplished most effectively when the swelling is fluctuant. A fluctuant swelling is a fluid-containing mass in which a wavelike sensation (like pushing on a water balloon) is felt when pressure is applied (see Fig. 10, B ; also Fig. 21.1, A ). Incising a fluctuant swelling releases purulence immediately and provides rapid relief. If the swelling is nonfluctuant or firm, incision for drainage often results in drainage of only blood and serous fluids. Incision and drainage of a nonfluctuant abscess reduces pressure and facilitates healing by reducing irritants and increasing circulation in the area.

Contraindications

There are relatively few contraindications to the use of incision for drainage. Patients with prolonged bleeding or clotting times or those who are on bisphosphonates must be treated with caution, and hematologic screening is often indicated. An abscess in or near an anatomic space should be handled very carefully.

Procedures

Anesthesia

Profound anesthesia is difficult to obtain in the presence of inflammation, swelling, or exudates. Because direct subperiosteal infiltration is ineffective and may be quite painful, regional block anesthetic techniques are preferred. Mandibular blocks for posterior areas, bilateral mental blocks for the anterior mandible, posterior superior alveolar blocks for the posterior maxilla, and infraorbital blocks for the premaxilla area are the preferred choices. These injections may be supplemented by regional infiltration.

In addition to block anesthesia, one of the following methods may also be used. The first technique is infiltration that starts peripheral to the swelling. After the application of topical anesthetic, the solution is injected slowly with limited pressure and depth; this is followed by additional injections in previously anesthetized tissue, moving progressively closer to the center of the swelling. This procedure results in improved anesthesia without extreme discomfort.

The second technique is the use of topical ethyl chloride. A stream of this solution is directed onto the swelling from a distance, and the liquid is allowed to volatilize on the tissue surface. Within seconds, the tissue at the site of volatilization turns white. The incision is quickly accomplished with continued ethyl chloride spray. This topical anesthesia is a supplement to block anesthesia when a quick incision is required.

If neither of these procedures work, nitrous oxide/oxygen sedation or intravenous (IV) sedation can be used for incision and drainage.

Incision

After anesthesia has been induced, the incision is made vertically with a No. 11 scalpel. Vertical incisions are made parallel to the major blood vessels and nerves and leave very little scarring. The incision should be made firmly through periosteum to bone. If the swelling is fluctuant, pus usually flows immediately, followed by blood. If the swelling is nonfluctuant, the predominant drainage is blood.

Drainage

After the initial incision, a small, closed hemostat may be placed in the incision and then opened to enlarge the draining tract. This procedure is indicated with more extensive swelling. To maintain a path for drainage, an I-shaped or “Christmas tree” drain cut from a rubber dam or a piece of iodoform gauze can be placed (suturing is optional) in the incision (see Fig. 10.5 ). The drain should be removed after 2 to 3 days; if it is not sutured, the patient may remove the drain at home.

Periapical Surgery

Periapical surgery (PAS) is commonly performed to remove a portion of the root with undebrided canal space or to seal the canal apically when a complete seal cannot be accomplished with nonsurgical root canal treatment through an orthograde approach.

Indications

The main indications for PAS are anatomic complexity of the root canal system, procedural accidents, irretrievable materials in the root canal, symptomatic cases, and horizontal apical fracture, in addition to biopsy and corrective surgery.

Anatomic Problems

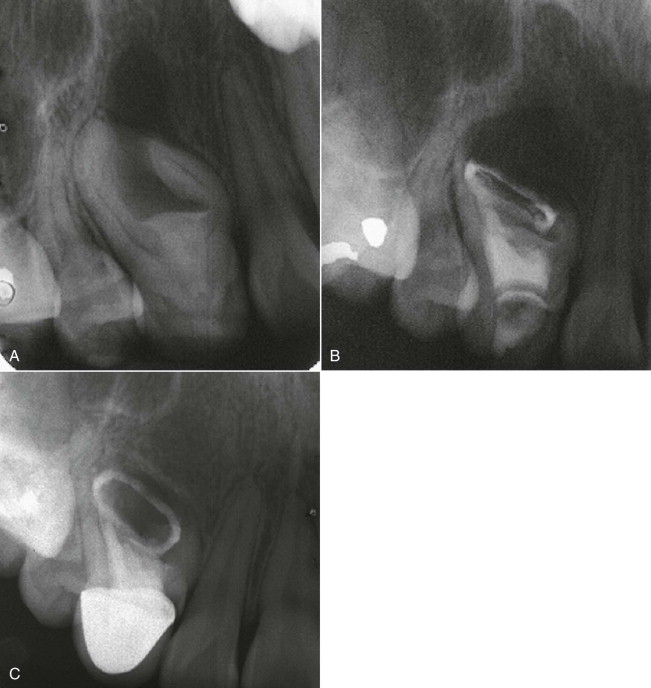

A nonnegotiable, blocked canal or severe root curvature may prevent adequate cleaning and shaping or obturation. Nonsurgical (and surgical) endodontic treatments are indicated in these cases ( Fig. 21.2 ). Nonsurgical root canal therapy or revision (if possible) before surgery improves the surgical success rate. However, if neither is feasible, removal of the uninstrumented and unfilled portion of the root or PAS may be necessary ( Fig. 21.3 ).

Anatomic perforation of the root apex through the bone (fenestration), although infrequent, may necessitate PAS after root canal treatment. Reducing the root apex to place it within the bone corrects this condition. Occasionally, adequate root canal therapy is compromised by extensive apical root resorption. It may then be necessary to expose the root, remove the resorbed area, and repair it.

Procedural Accidents

Separated instruments, ledging, perforations, and gross overfills may cause failure of root canal treatment, requiring surgical intervention. If symptoms or lesions develop or persist after the accidents, PAS is usually necessary (see Fig. 19.14 ; also Fig. 21.4 ).

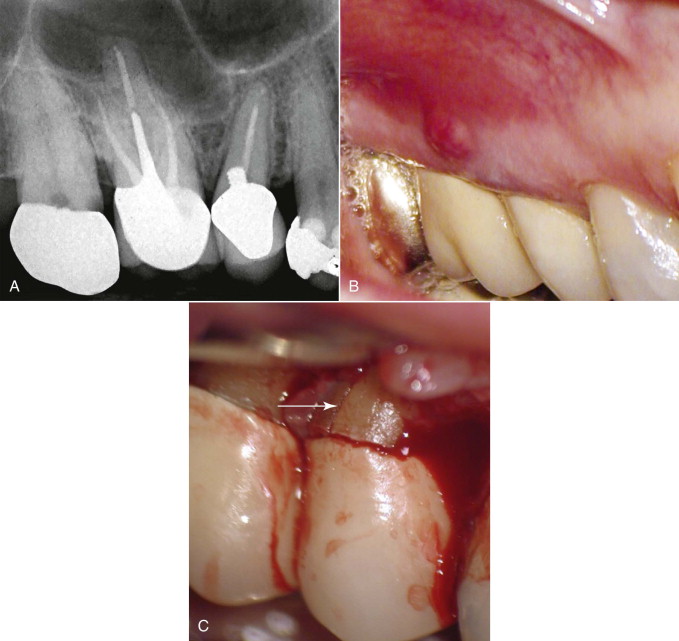

Irretrievable Materials in the Root Canal

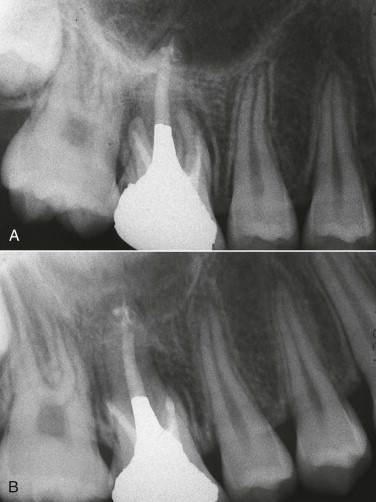

Retreatment (revision) is recommended for treatment of failures. However, irretrievable posts or dowels or root filling materials, such as silver cones, amalgam, or nonabsorbable pastes, often prevent revision, or their removal would result in further damage to the root structure. The best alternative is a surgical approach and placement of a root-end filling material ( Fig. 21.5 ).

Symptomatic Cases

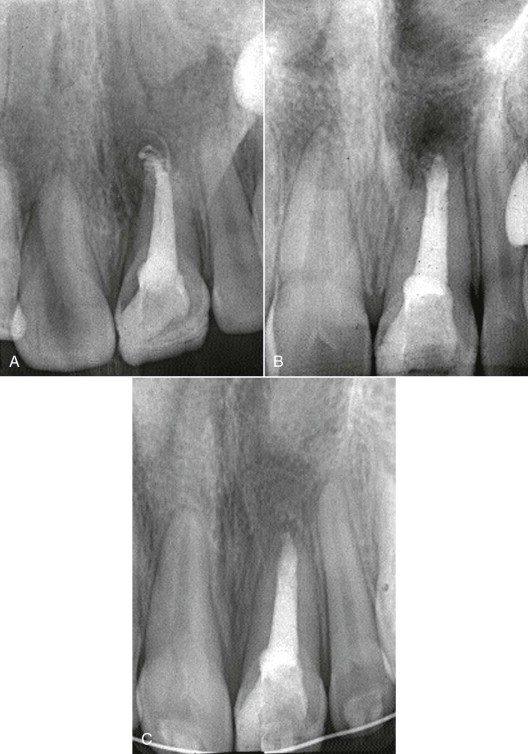

Most symptoms disappear after complete cleaning and obturation of root canals. However, when symptoms persist after meticulous performance of these procedures, PAS should be considered to identify the cause or causes of the persistence of the symptoms. The main cause of the persistence of pain in these cases is usually inflammation that results from the inability of the operator to completely clean the root canal or canals. Exploratory surgery may identify undetected vertical root fractures ( Fig. 21.6 ), additional apical and lateral foramina (possible missed canals), perforations, apical ramifications, overfills, or other causes of failure. Once the cause has been eliminated, the symptoms disappear.

Horizontal Apical Fracture

Although most traumatic horizontal apical fractures usually heal without intervention, occasionally the apical portion of a root becomes necrotic and cannot be treated nonsurgically. In these cases, the apical portion of the root should be removed and the apical seal should be evaluated.

Biopsy

Although most periapical lesions are of pulpal origin, nonpulpal lesions do exist (see Chapter 5 for diagnosis and treatment planning). The presence of a vital pulp in a tooth with a radicular radiolucency ( Fig. 21.7 ), undefined periapical lesions in teeth with vital pulps in patients with a history of previous malignancy, and lip paresthesia or anesthesia are indications for biopsy.

Contraindications

The four major contraindications to PAS are (1) anatomic factors, (2) medical or systemic complications, (3) indiscriminate use of surgery, and (4) an unidentified cause of treatment failure.

Anatomic Factors

Inaccessibility of the surgical site because of tooth location, spaces (e.g., maxillary sinus or nasal fossa), unusual bony configuration, or proximity of neurovascular bundles may be a contraindication or at least require caution or special approaches ( Fig. 21.8 ). For example, a thick external oblique ridge associated with a mandibular molar or apices contiguous with the mandibular canal may compromise surgical access. Other situations that may contraindicate PAS or modify the approaches used include very short root length (precluding root-end resection), severe periodontal disease (prognosis hopeless, even with surgery), and unrestorable teeth.

Medical or Systemic Complications

Serious systemic health problems or extreme apprehension make the patient a poor candidate for PAS. Surgery may also be contraindicated in patients with blood disorders, terminal disease, uncontrolled diabetes, or severe heart disease and in those whose immune systems are compromised.

Indiscriminate Use of Surgery

As previously stated, surgery is not indicated when a nonsurgical approach is possible and would probably result in success Fig. 21.9 . The practice of managing all accessible periapical lesions or large periradicular lesions surgically is unethical and contraindicated. A recent systematic review comparing treatment outcomes for endodontic surgery and nonsurgical retreatment found an initial higher success rate for surgery at 2 to 4 years, but a significant shift in favor of nonsurgical retreatment at 4 to 6 years. This finding supports the position that nonsurgical retreatment should usually be the first choice when possible.

Unidentified Cause of Treatment Failure

Using surgery to correct a treatment failure for which the cause cannot be identified is unlikely to be successful.

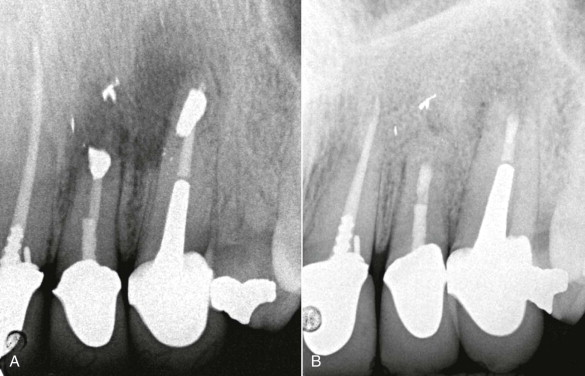

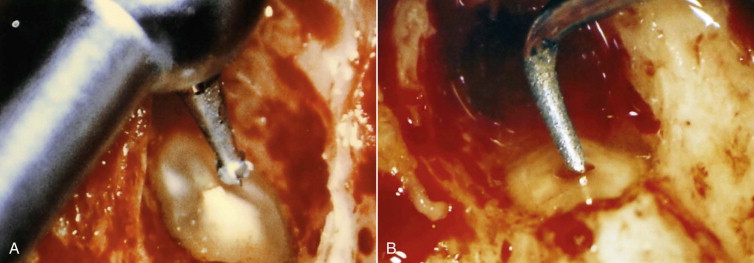

Recent Advances in Endodontic Surgery

Many advances in surgical technique and instrumentation have occurred over the past 10 to 15 years. These include enhanced magnification and illumination, ultrasonic tips, microinstruments, and newer root-end filling materials. Enhanced illumination and magnification have greatly improved the procedures that practitioners can perform. Magnification in endodontic surgery has led to miniaturization of endodontic surgical instruments ( Figs. 21.10 to 21.13 ). Developments in root-end filling materials have increased both the quality and biocompatibility of the apical seal. Cone beam volumetric tomography (CBVT) is an emerging technology with many applications in endodontic diagnosis and treatment, including presurgical treatment planning. Compared to traditional two-dimensional imaging, CBVT has the unique ability to provide high-resolution images in three dimensions while eliminating superimposition of surrounding anatomic structures.

Together, these advances have significantly improved the state of the art and science of endodontic surgery, giving a second chance to a tooth that traditionally would have been considered for extraction.

Procedures Involved in Periapical Surgery

The typical sequence of procedures in PAS is as follows: flap design, incision and reflection, apical access, periradicular curettage, root-end resection, root-end cavity preparation, root-end filling, flap replacement and suturing, postoperative care and instructions, and suture removal and evaluation.

Flap Design

The first step in PAS is designing a flap that allows adequate exposure of the site of the surgery. The following general guidelines and principles should be used during flap design.

- 1.

The flap should be designed for maximum access to the site of surgery.

- 2.

An adequate blood supply to the reflected tissue is maintained with a wide flap base.

- 3.

Incisions over bony defects or over the periradicular lesion should be avoided; these might cause postsurgical soft tissue fenestrations or nonunion of the incision.

- 4.

The actual bony defect is larger than the size observed radiographically.

- 5.

A minimal flap, which should include at least one tooth on either side of the intended tooth, should be used.

- 6.

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses