-

Chapter Outline

-

Pathways of Communication Between the Dental Pulp and the Periodontium

-

Effect of Pulpal Diseases and Endodontic Procedures on the Periodontium

-

Clinical and Radiographic Tests for Diagnosis of Endodontic-Periodontic Lesions

-

Classification and Differential Diagnosis of Endodontic-Periodontic Lesions

Learning Objectives

After reading this chapter, the student should be able to:

- 1.

Delineate the anatomic pathways of communication between the dental pulp and the periradicular tissues.

- 2.

Describe the effects of pulpal diseases and endodontic procedures on the periodontium.

- 3.

Describe the effects of periodontal disease and procedures on the dental pulp.

- 4.

Identify the clinical and radiographic findings that are important to identify the origin of periodontal pockets.

- 5.

Know the clinical classification of endodontic-periodontal diseases.

- 6.

Identify prognoses and assess which cases should be considered for referral.

A periodontist refers a 46-year-old patient with no contributing medical history to an endodontic office for diagnosis and possible root canal treatment. The patient states that he has been treated for periodontal disease for a few years by a periodontist. His chief complaint is “having a recent localized gumboil in one of his front teeth.” Clinical examination shows that the patient has generalized moderate periodontitis and a localized severe periodontitis around the maxillary left lateral incisor. This tooth has no restoration and is sensitive to percussion and palpation. The pulp of the left lateral incisor responds within normal limits compared to the contralateral and adjacent teeth. Periodontal probing of this tooth reveals the presence of pockets with depths ranging from 3 to 9 mm. Radiographic examination of the patient reveals the presence of moderate bone loss around most of the maxillary anterior teeth with localized triangular bone loss around the left lateral incisor. No periapical radiolucency is noted around this tooth.

The endodontist contacts the referring periodontist and informs him that the periodontal pockets around the left lateral incisor are of periodontal origin and root canal treatment would not affect the prognosis of this tooth. The periodontist states that the periodontal condition around this tooth has been stable for some time and that the patient had recently developed deep pockets. The periodontist thinks that the pulp is involved and that root canal treatment will improve the periodontal condition around this tooth. The endodontist disagrees with his colleague, and the patient is caught in the middle of this discussion. Although it may seem unlikely, this type of scenario is played out daily in dental offices around the world. It demonstrates the clinical importance of the interrelation of endodontic and periodontics lesions.

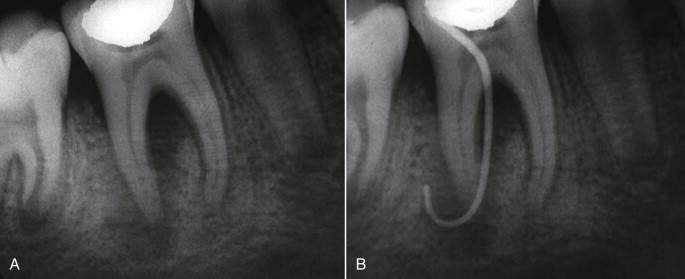

A number of investigations have shown that the presence of microorganisms is essential for the development of pulpal and/or periradicular pathosis. Cultures from infected root canals show the predominant presence of gram-negative anaerobic bacteria. These bacteria enter the root canals through direct pulp exposures (caries or traumatic injuries) or by coronal microleakage. Egress of bacteria or their byproducts from pathologically involved pulps into the periradicular tissues results in inflammatory and immunologic reactions in this region. The extent of the periradicular lesion depends on the virulence of the bacteria present in the root canal system and the immune response during the disease process. Periradicular changes vary from a confined apical lesion to an extensive lesion communicating with the oral cavity via a sinus tract ( Fig. 7.1 ) along the root surface as a periodontal pocket.

Examination of the pathologic changes in the coronal periodontium during periodontitis shows that the mechanisms involved in periodontal disease are similar to those involved in the pathogenesis of periapical lesions. The main differences between the two processes are their original source and the direction of their progression. Periapical lesions extend apically or coronally, whereas periodontal lesions tend to extend only apically. As expected, these lesions can mimic each other at one or another stage of their development and make differential diagnosis difficult (see Fig. 7.1 ).

The decision on whether a tooth with a periodontal pocket requires endodontic therapy or periodontal treatment (or both) should be based on correct diagnosis. It is critical to examine all systematically obtained data during the patient examination before instituting proper treatment. Careful diagnosis prevents misunderstanding between patients and dentists involved in the treatment of endodontic-periodontic lesions. The purpose of this chapter is to discuss various aspects of this issue, including (1) pathways of communication between pulp and periodontium; (2) effects of periodontal disease and procedures on the pulp; (3) effects of endodontic lesions and procedures on the periodontium; (4) clinical and radiographic diagnostic procedures; and (5) classification of these lesions.

Learning Objectives

After reading this chapter, the student should be able to:

- 1.

Delineate the anatomic pathways of communication between the dental pulp and the periradicular tissues.

- 2.

Describe the effects of pulpal diseases and endodontic procedures on the periodontium.

- 3.

Describe the effects of periodontal disease and procedures on the dental pulp.

- 4.

Identify the clinical and radiographic findings that are important to identify the origin of periodontal pockets.

- 5.

Know the clinical classification of endodontic-periodontal diseases.

- 6.

Identify prognoses and assess which cases should be considered for referral.

A periodontist refers a 46-year-old patient with no contributing medical history to an endodontic office for diagnosis and possible root canal treatment. The patient states that he has been treated for periodontal disease for a few years by a periodontist. His chief complaint is “having a recent localized gumboil in one of his front teeth.” Clinical examination shows that the patient has generalized moderate periodontitis and a localized severe periodontitis around the maxillary left lateral incisor. This tooth has no restoration and is sensitive to percussion and palpation. The pulp of the left lateral incisor responds within normal limits compared to the contralateral and adjacent teeth. Periodontal probing of this tooth reveals the presence of pockets with depths ranging from 3 to 9 mm. Radiographic examination of the patient reveals the presence of moderate bone loss around most of the maxillary anterior teeth with localized triangular bone loss around the left lateral incisor. No periapical radiolucency is noted around this tooth.

The endodontist contacts the referring periodontist and informs him that the periodontal pockets around the left lateral incisor are of periodontal origin and root canal treatment would not affect the prognosis of this tooth. The periodontist states that the periodontal condition around this tooth has been stable for some time and that the patient had recently developed deep pockets. The periodontist thinks that the pulp is involved and that root canal treatment will improve the periodontal condition around this tooth. The endodontist disagrees with his colleague, and the patient is caught in the middle of this discussion. Although it may seem unlikely, this type of scenario is played out daily in dental offices around the world. It demonstrates the clinical importance of the interrelation of endodontic and periodontics lesions.

A number of investigations have shown that the presence of microorganisms is essential for the development of pulpal and/or periradicular pathosis. Cultures from infected root canals show the predominant presence of gram-negative anaerobic bacteria. These bacteria enter the root canals through direct pulp exposures (caries or traumatic injuries) or by coronal microleakage. Egress of bacteria or their byproducts from pathologically involved pulps into the periradicular tissues results in inflammatory and immunologic reactions in this region. The extent of the periradicular lesion depends on the virulence of the bacteria present in the root canal system and the immune response during the disease process. Periradicular changes vary from a confined apical lesion to an extensive lesion communicating with the oral cavity via a sinus tract ( Fig. 7.1 ) along the root surface as a periodontal pocket.

Examination of the pathologic changes in the coronal periodontium during periodontitis shows that the mechanisms involved in periodontal disease are similar to those involved in the pathogenesis of periapical lesions. The main differences between the two processes are their original source and the direction of their progression. Periapical lesions extend apically or coronally, whereas periodontal lesions tend to extend only apically. As expected, these lesions can mimic each other at one or another stage of their development and make differential diagnosis difficult (see Fig. 7.1 ).

The decision on whether a tooth with a periodontal pocket requires endodontic therapy or periodontal treatment (or both) should be based on correct diagnosis. It is critical to examine all systematically obtained data during the patient examination before instituting proper treatment. Careful diagnosis prevents misunderstanding between patients and dentists involved in the treatment of endodontic-periodontic lesions. The purpose of this chapter is to discuss various aspects of this issue, including (1) pathways of communication between pulp and periodontium; (2) effects of periodontal disease and procedures on the pulp; (3) effects of endodontic lesions and procedures on the periodontium; (4) clinical and radiographic diagnostic procedures; and (5) classification of these lesions.

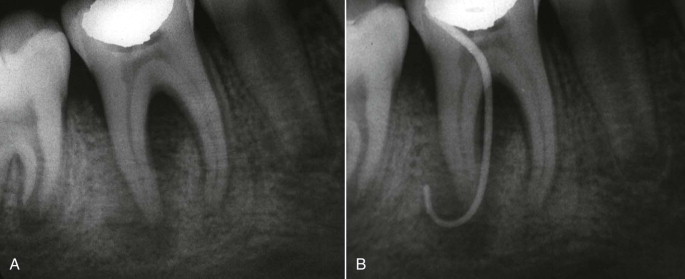

Pathways of Communication between the Dental Pulp and the Periodontium

Embryonically, the pulp and periodontium have an intimate relationship. The dental papilla, which becomes dental pulp later on in the life of a tooth, is derived from cells that have migrated from the neural crest. Tissues of the periodontium develop from the dental follicle. These ectomesenchymal tissues are separated by Hertwig’s epithelial root sheath ( Fig. 7.2 ). After formation of the first layer of dentin in the root, Hertwig’s sheath breaks up, allowing cells of the surrounding dental follicle to migrate and contact the newly formed dentin surface. The cells of the dental follicle differentiate into cementoblasts and initiate cementum formation. This acellular cementum ultimately serves as an anchor for the periodontal ligament (PDL) cells. As maturation of the root continues, direct communication between the pulp tissue and the periodontium becomes limited to the apical foramina and lateral canals. Congenital absence of cementum in the coronal portion of roots in some individuals or removal of it during periodontal treatment can result in communication between the periodontium and the dental pulp through exposed dentinal tubules. The pathways of communication between the pulp tissue and periodontium include the apical foramen, lateral or accessory canals, and dentinal tubules.

Apical Foramen

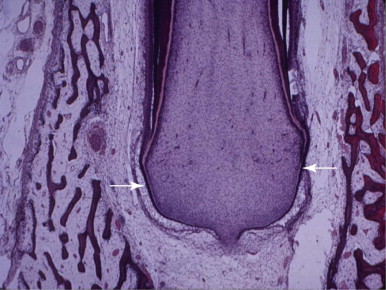

The apical foramen is the main pathway between the pulp and the PDL ( Fig. 7.3 ). There may be one foramen or multiple foramina at the apex. Multiple foramina occur more often in multirooted teeth. Egress of irritants from pathologically involved root canals via the apical foramen into periapical tissues initiates an inflammatory response and its consequences, such as destruction of the apical PDL and resorption of bone, cementum, and dentin.

Although a clear cause and effect relationship between pulpal diseases and inflammation in the apical periodontium via the apical foramen has been established, there is no substantial evidence that shows that periodontitis affects the viability of the dental pulp.

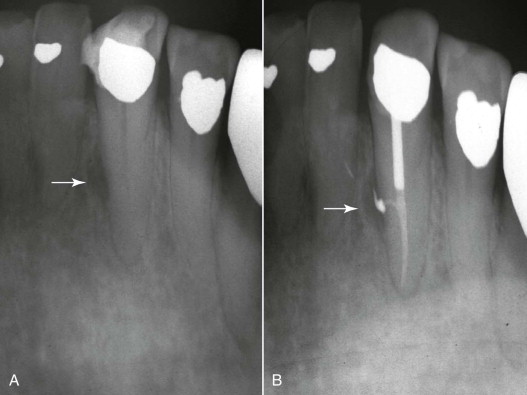

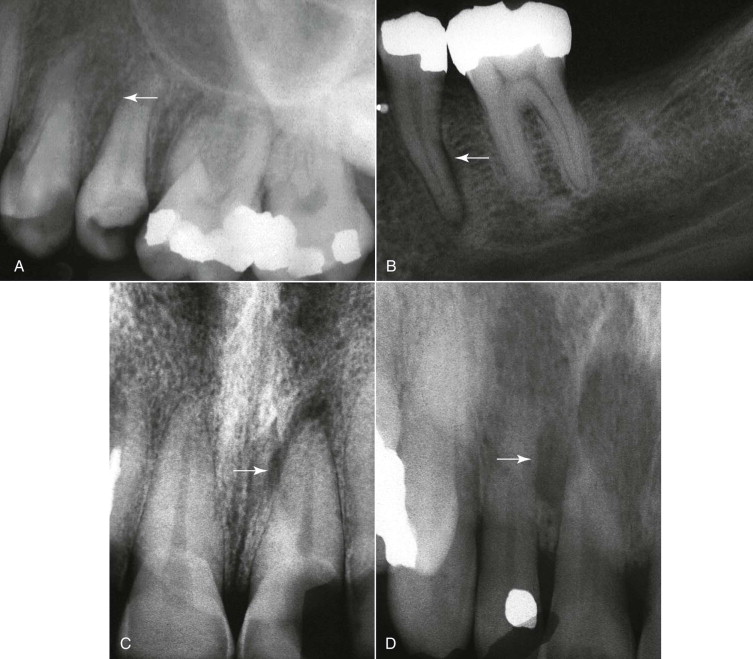

Lateral Canals

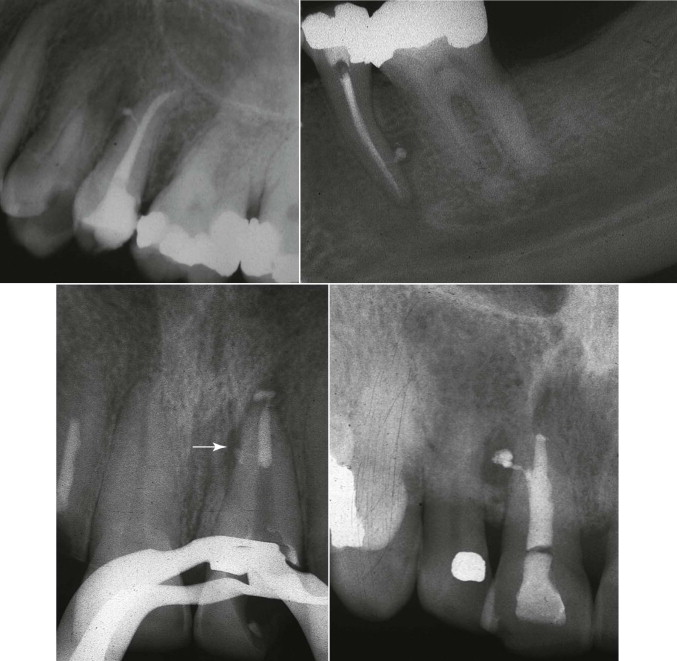

Lateral or accessory canals are formed when a localized area of epithelial root sheath breaks down before the root dentin is laid down. Formation of these canals results in direct communication between the pulp and the PDL. These canals can be single or multiple, small or large, and can be present anywhere along the roots ( Fig. 7.4 ). The incidence of these canals varies not only among different types of teeth, but also at different levels of roots. In general, lateral canals are present more frequently in posterior teeth than in anterior teeth and are found more frequently in the apical portions of roots than in their coronal segments. The incidence of lateral canals in the furcation of molars is reported to be as low as 2% to 3% and as high as 76.8%. A patent lateral canal can carry irritants from the pulp to the periodontium or vice versa. A lateral canal can carry enough irritants from a necrotic pulp to the periradicular tissues to induce a lateral lesion ( Fig. 7.5, A ). However, pulpal pathosis rarely occurs in teeth with periodontal involvement through the lateral canals. This phenomenon is attributed to the defense of vital pulp against irritants coming from the periodontium.

Lack of severe changes, such as irreversible pulpitis or pulpal necrosis, has been demonstrated in histologic sections of teeth with severe periodontal disease. Despite their frequent presence in the roots, lateral canals are not usually visible on standard radiographs. They are usually revealed only when filled with radiopaque materials such as endodontic sealers, after obturation of the root canal system ( Fig. 7.5, B ). The main radiographic indicators of the presence of lateral canals before obturation are (1) a notch on the lateral root surface, (2) localized thickening of the PDL on the lateral surface of the root, and (3) a frank lateral lesion in periradicular tissues ( Fig. 7.6 ). The location and size of lateral canals are usually revealed when they are filled with root canal filling materials ( Fig. 7.7 ). The presence of infected lateral canals can be the cause of persistent narrow periodontal pockets that do not extend into the apical foramen after adequate root canal therapy.

Dentinal Tubules

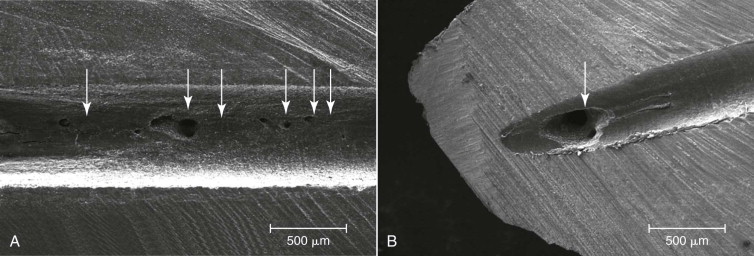

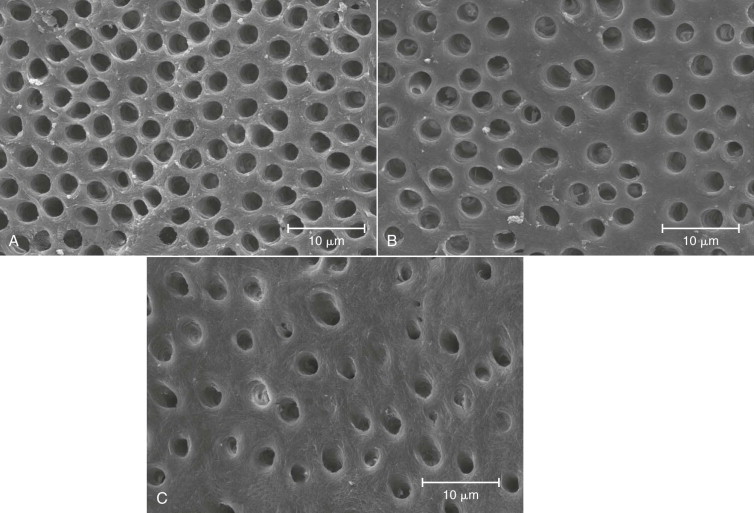

In the root, the dentinal tubules extend from the pulp to the cementodentinal junction (CDJ). These tubules run a relatively straight course between the pulp and the cementum on the root surfaces. Their diameter ranges from about 1 to 3 µm. The tubules in the coronal root are larger than those in the apical root ( Fig. 7.8 ). The number of dentinal tubules per square millimeter has been reported to range from 4,900 to 90,000. The size and number of dentinal tubules decreases in the coronal-apical direction ( Fig. 7.8 ). At the cementoenamel junction (CEJ), the number of dentinal tubules has been estimated to be approximately 15,000 per square millimeter. The dentinal tubules contain odontoblastic processes, nerve fibers, and tissue fluid. As the tooth ages or becomes irritated, the tubules calcify and decrease in number.

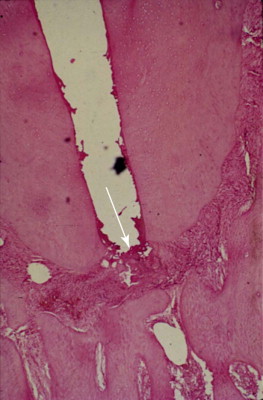

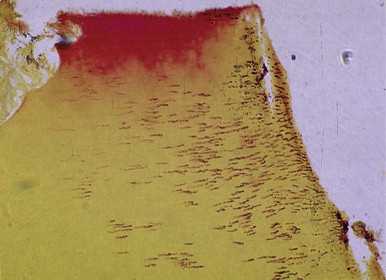

Studies have shown that bacteria present in infected root canals invade the dentinal tubules ( Fig. 7.9 ). The presence of a continuous layer of cementum is an effective barrier against the penetration of bacteria and their byproducts from the pathologically involved root canals into the periodontium and vice versa. Congenital absence of cementum over root dentin at the CEJ, caries, or removal of the cementum during periodontal treatment can result in the opening of numerous channels of communication between the pulp and the periradicular tissues. Theoretically, these channels can carry toxic metabolites present in infected root canals or infected periodontium in both directions. However, it has been shown that root surfaces denuded of cementum and exposed to the oral cavity do not cause significant changes in the pulp.

Outward movement of dentinal tissue fluid and the tubular contents of vital pulps can delay intratubular invasion by bacteria. Accumulated host defense cells and inflammatory mediators at the site of exposure, dentinal sclerosis, and reparative dentin also limit or even prevent bacterial invasion of the pulp via dentinal tubules. These protective factors become less effective when dentin thickness is considerably reduced and dentin permeability, therefore, is significantly increased. On the other hand, if the pulp is necrotic, exposed dentinal tubules can become true avenues for bacteria to reach and colonize the pulp. Nagaoka and associates have shown that bacterial invasion of dentinal tubules occurs more rapidly in teeth with necrotic pulps than in those with vital pulps.

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses