Oral appliances (OAs) are a primary treatment option for snoring and mild to moderate obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) and are implemented as a noninvasive alternative for patients with severe OSA who are unwilling or unable to tolerate continuous positive airway pressure for the management of their disease. Studies have demonstrated the ability of OAs to eliminate or significantly reduce the symptoms of OSA and produce a measurable influence on the long-term health effects of the disease. Most studies have evaluated one type of OAs, the mandibular advancement splints. This article describes the effectiveness and outcomes of mandibular advancement splints.

Oral appliances (OAs) are indicated as a primary treatment option for snoring and mild to moderate obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) and are also being implemented as a noninvasive alternative for patients with severe OSA who are unwilling or unable to tolerate continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) for the management of their disease. CPAP is an effective treatment for the management of sleep-disordered breathing in both adults and children but has low adherence rates. Therefore, OAs play an important role in the therapy for patients with OSA. There is continued emergence of studies demonstrating the ability of OAs to eliminate or significantly reduce the symptoms of OSA and produce a measurable influence on the long-term health effects of the disease. Most studies have evaluated one type of OA, mandibular advancement splints (MAS). Therefore, this article describes the effectiveness and outcomes of MAS.

Over the past decade, several randomized controlled clinical trials have been conducted comparing the effects of MAS against both placebo devices and CPAP. The efficacy of MAS has been reviewed previously, including a Cochrane review and a practice parameter update by the American Academy of Sleep Medicine ; all together, there is a considerable body of evidence toward the efficacy of MAS in the treatment of OSA. To summarize the efficacy studies, in randomized controlled trials comparing MAS with placebo, MAS have been shown to significantly improve objective sleep measurements, such as the apnea-hypopnea index (AHI), arousal index, snoring, and in some but not all studies, arterial oxygen desaturation. MAS have also been shown to significantly improve subjective and objective measurements of sleepiness, quality of life, and 24-hour blood pressure measurement devices. A variety of randomized controlled trials have compared the efficacy of MAS with CPAP. According to these trials, both CPAP and MAS improved objective sleep measurements, such as AHI, arousal index, and minimum arterial oxygen saturation. Although CPAP and MAS have similar improvements in cardiovascular outcomes and inflammatory markers, the magnitude of improvements in AHI and oxygen saturation was significantly greater with CPAP. This contradiction may likely be related to a higher adherence to MAS compared with CPAP in terms of hours per night and nights per week of usage. Table 1 summarizes the outcomes of the most recent studies.

| Author, Year, Reference Number of Patients |

Measurements | Significant Changes Compared with Baseline | Significant Changes Compared with CPAP | Patients Who Preferred a Treatment (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hoekema et al, 2007 N = 20 |

PSG ESS Driving performance |

MAS and CPAP improved AHI, min SaO2 Both improved ESS CPAP and MAS improved |

MAS = CPAP MAS = CPAP MAS = CPAP |

N/A Parallel study |

| Hoekema et al, 2008 N = 28 |

NT-pro-BNP | MAS showed improvement | Only MAS improved NT-pro-BNP | N/A Parallel study |

| Gagnadoux et al, 2009 N = 69 |

PSG Nottinham QoL Osler test |

MAS and CPAP improved AHI Improvement Improvement |

CPAP>MAS MAS = CPAP MAS = CPAP |

71.2% MAS 8.5% CPAP 14.5% MAS = CPAP |

| Trzepizur et al, 2009 N = 12 |

Microvascular reactivity PSG Blood pressure |

MAS and CPAP Improvement AHI and ODI No difference |

MAS = CPAP MAS = CPAP MAS = CPAP |

Not described |

| Aarab et al, 2011 N = 57 |

PSG ESS |

Improvement AHI Improvement |

MAS = CPAP MAS = CPAP |

N/A Parallel study |

| Aarab et al, 2011 N = 43 |

PSG after 1 y ESS |

Stable AHI improvement Additional sleepiness improvement |

CPAP>MAS MAS = CPAP |

N/A Parallel study |

| Holley et al, 2011 N = 378 |

PSG | Improved AHI | MAS = CPAP for mild to moderate CPAP>MAS severe OSA |

Not described |

MAS increase the upper airway by preventing the tongue and soft tissues of the throat from collapsing into the pharynx while holding the mandible and attached soft tissues, including the tongue base forward, which enlarges the upper airway dimensions by specifically increasing the lateral dimensions of the velopharynx.

Factors impacting the effectiveness of OSA treatment with MAS

Adherence

Adherence has been defined by the World Health Organization as “the extent to which a person’s behavior – taking medications, following a diet, and/or executing lifestyle changes, such as using CPAP or MAS every night – correspond with agreed recommendations from a heath care provider.” Poor adherence to long-term treatment is often a problem faced by health professionals, and unfortunately there is a paucity of specific training in adherence management for practitioners. To improve adherence, it is known that a patient-centered treatment approach is crucial and patient preferences and lifestyle has to be taken into account. The consequences of a nontailored method with poor patient adherence are related to poor health outcomes and increased health care costs.

The effectiveness of mandibular advancement device (MAD) therapy depends on patient adherence to wear the device comfortably, and appliances that are custom made and adjustable have been found to be more effective than the fixed, thermoplastic-type appliances. Vanderveken and collaborators have shown that prefabricated, off-the-shelf appliances are less effective and less accepted by patients and, therefore, should not be used either as a therapeutic option or as a screening tool to predict MAS responders.

An area where MAS are described to excel compared with CPAP is the rate of patient adherence to the prescribed treatment regimen. Adherence is usually measured subjectively, and self-reported compliance with appliance use has been reported to be as high as 96% in patients using MAS for more than 75% of nights and 80% in patients using MAD more than 75% of each night. The bias that can accompany self-reported adherence is highlighted by one study whereby a compliance monitor indicated that the MAD was worn for a mean of 6.8 hours per night.

According to randomized controlled trials, CPAP therapy is consistently more effective at reducing sleep-disordered breathing events, but patients tolerate MAS better. The superior patient satisfaction associated with the use of MAS reflects the relative simplicity and convenience of this form of treatment. Despite residual apneas with MAS, or a higher efficacy rate of CPAP in reducing the AHI, the similarities in treatment outcomes have been previously hypothesized to be related to the numbers of hours per night of use. MAS used for prolonged hours with partial efficacy may result in similar outcomes compared with CPAP being fully effective for only part of the night. A patient-tailored treatment is synonymous with good medicine, and life-long therapies are dependent on patients’ cooperation and adherence. It is important to include patients in the decision of their treatment and offer more than one type of therapy for patients with OSA who are potentially good candidates for MAS therapy.

Titration

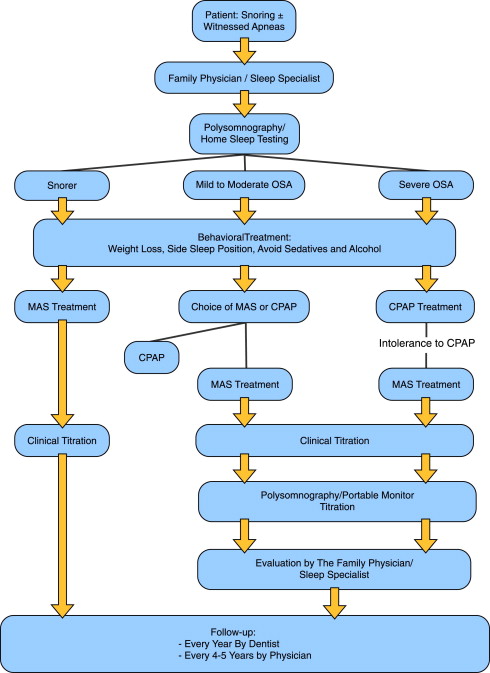

Analogous to the pressure of a CPAP mask, the amount of mandibular advancement produced by a MAD that will effectively reduce the number of apneas will vary from patient to patient. The amount of pressure required for each patient cannot be predetermined based on OSA severity or craniofacial characteristics; as such the magnitude of advancement needs to be determined through a titration procedure. Typically, the amount of advancement is initially set at 66% of maximum protrusion, and over a period of weeks, patients slowly increase the advancement by adjusting the appliance until there is resolution of subjective OSA symptoms. At this point, a follow-up polysomnogram (PSG) with the device worn is required to ensure adequate improvement to breathing during sleep. A schematic of the treatment protocol can be seen in Fig. 1 .

Additional advancement of the appliance by titration carried out during this follow-up PSG has been shown to further increase the success rate of OA therapy. This advancement is achieved by simply having the sleep technologist wake and ask the patient to increase the protrusion of the appliance should there be persistent snoring or events related to adverse breathing. Several studies have evaluated whether a titration of mandibular advancement during polysomnography could be used as a predictor and accelerate MAS treatment, similar to CPAP titration. These studies had mixed results in predicting the amount of mandibular advancement needed for successful MAS therapy, and overnight titration of MAS at appliance delivery remains an experimental approach.

The importance of titration to enhance the efficacy of MAS therapy is highlighted by a closer examination of randomized controlled trials (see Table 1 ) comparing CPAP to MAS. Most of these studies have found that MAS and CPAP have a similar impact on daytime sleepiness and quality of life. In 2 other studies, Engleman and Lam have reported an inferiority of MAS compared with CPAP; however, it is important to note that fixed, nontitratable, single-jaw position appliances were used for their patients. Previous reports on effective single-jaw positioners have proposed that, if this type of appliance is used, there should be the opportunity to remake these devices with further mandibular advancement, which represents titration with multiple appliances. Also, the increased likelihood of providing successful therapy with adjustable compared with fixed appliances is especially evident in cases of moderate and severe OSA. It is clear in the literature that customizing the fit of the MAS, with the use of a custom-made appliance to the patient’s specific oral anatomy, and determining the ideal anterior position of the mandible via titration of the amount of advancement are crucial to optimizing the effectiveness of therapy.

Appliance design

There are a multitude of MAS designs with various methods of adjustment and retention mechanisms available on the marketplace today. As such it is easy to imagine these differences contributing to some of the variability observed in the results of clinical studies investigating MAS effectiveness. The possible influence of various MAS design features on the management of subjective symptoms during OSA treatment was recently examined in a systematic review. The results suggest that an appliance with titratable mandibular advancement that is found acceptable by patients because of greater comfort and retention, and being custom made (not prefabricated), will be successful at improving sleep-disordered breathing signs and symptoms. It is also noted that the optimum amount of advancement might not necessarily be the maximum achievable forward position of the mandible. The investigators also reported that the amount of vertical opening did not impact significantly on the appliance design. Isono and collaborators found that an increase in jaw opening would decrease the upper airway area. Pitsis and colleagues found that a 10-mm increase in the jaw opening did not make significant differences in the AHI, but a highest percentage of patients developed temporomandibular joint symptoms with the greater jaw opening. More recently Nikolopoulou and collaborators evaluated an increase in vertical dimensions without mandibular advancement. They concluded that without mandibular protrusion an increase in vertical dimension was associated with an aggravation of OSA. In summary, there is no preferred MAD design, as long as it is properly custom made for the patient, patient comfort is achieved, it has good retention, and most importantly allows for mandibular advancement and titration to optimize treatment outcome.

Appliance design

There are a multitude of MAS designs with various methods of adjustment and retention mechanisms available on the marketplace today. As such it is easy to imagine these differences contributing to some of the variability observed in the results of clinical studies investigating MAS effectiveness. The possible influence of various MAS design features on the management of subjective symptoms during OSA treatment was recently examined in a systematic review. The results suggest that an appliance with titratable mandibular advancement that is found acceptable by patients because of greater comfort and retention, and being custom made (not prefabricated), will be successful at improving sleep-disordered breathing signs and symptoms. It is also noted that the optimum amount of advancement might not necessarily be the maximum achievable forward position of the mandible. The investigators also reported that the amount of vertical opening did not impact significantly on the appliance design. Isono and collaborators found that an increase in jaw opening would decrease the upper airway area. Pitsis and colleagues found that a 10-mm increase in the jaw opening did not make significant differences in the AHI, but a highest percentage of patients developed temporomandibular joint symptoms with the greater jaw opening. More recently Nikolopoulou and collaborators evaluated an increase in vertical dimensions without mandibular advancement. They concluded that without mandibular protrusion an increase in vertical dimension was associated with an aggravation of OSA. In summary, there is no preferred MAD design, as long as it is properly custom made for the patient, patient comfort is achieved, it has good retention, and most importantly allows for mandibular advancement and titration to optimize treatment outcome.

MAS effects on sleepiness and quality of life

MAS have been shown to be effective in improving subjective and objective daytime sleepiness in patients with OSAS when compared with placebo and improves sleepiness to the same degree as the CPAP. Aarab and colleagues examined the effects of MAS and CPAP treatment 12 months following initial titration for patients with mild to moderate OSA. They found that CPAP reduced AHI slightly better than MAS and that the improvements in AHI were stable over the 12-month time period; however, subjective sleepiness progressively improved for all patients in the same time frame. They concluded that a lack of long-term differences in improvements in sleepiness between the MAS and the CPAP groups may indicate that the larger improvements in AHI values in the CPAP group are not clinically relevant. Johal and collaborators found that MAS therapy significantly improved the energy/vitality domain of quality of life and reduced subjective sleepiness in a group of patients with OSA preselected for a favorable treatment outcome using sleep nasendoscopy. Similar improvements were not seen in a conservatively managed group. There were some interesting findings in a study from Gagnadoux and colleagues whereby MAS showed a greater improvement compared with CPAP in a variety of profiles of quality of life (Nottingham Health Profile), such as physical mobility, social isolation, pain, emotional function, and sleep. MAS treatment may not improve AHI as much as CPAP, but consistently throughout various studies, does significantly improve their quality of life. For patients to adhere to treatment, it is crucial that patients feel better and acknowledge the importance of treatment.

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses