Early childhood caries (ECC), common in preschoolers, can lead to pain and infection if left untreated. Yet, ECC is largely preventable, and if it is identified early and the responsible risk factors are addressed, its progression can be halted or slowed. This article reviews the rationale for a first dental visit by age 1 year, caries risk assessment, and risk-based prevention and management of ECC and discusses strategies for providers to implement these contemporary evidence-based concepts into clinical practice.

Key Points

- •

Early childhood caries (ECC), a common chronic disease that can progress rapidly if left untreated, is largely preventable.

- •

To reduce the risk of ECC, children should have a first dental visit and establish a dental home by 1 year of age to receive risk-based primary prevention and counseling.

- •

ECC cannot be addressed successfully by restorative treatment alone and requires changes to dietary and oral hygiene practices.

- •

If ECC is identified early and the responsible risk factors are addressed, the progression of ECC can be halted or slowed.

- •

Effective ECC management requires using risk-based disease prevention and management approaches that include caries risk assessment, self-management goals, and caries remineralization strategies.

Introduction

Early childhood caries (ECC) is the most common chronic condition among children in the United States. In 2-year-olds to 5-year-olds, caries rates are on the increase, having increased 15% in recent years to 28%. Children of minority or low-income families are disproportionately affected and are less likely to receive timely care.

ECC is a particularly virulent form of caries that affects the primary teeth of infants and preschool children. Typically, decay begins on the maxillary incisors followed by maxillary and mandibular molars, affecting teeth sequentially as they erupt. ECC can progress rapidly if left untreated, resulting in pain and infection. Yet, ECC is largely preventable, and if it is identified early and the responsible risk factors are addressed, its progression can be halted or slowed.

Introduction

Early childhood caries (ECC) is the most common chronic condition among children in the United States. In 2-year-olds to 5-year-olds, caries rates are on the increase, having increased 15% in recent years to 28%. Children of minority or low-income families are disproportionately affected and are less likely to receive timely care.

ECC is a particularly virulent form of caries that affects the primary teeth of infants and preschool children. Typically, decay begins on the maxillary incisors followed by maxillary and mandibular molars, affecting teeth sequentially as they erupt. ECC can progress rapidly if left untreated, resulting in pain and infection. Yet, ECC is largely preventable, and if it is identified early and the responsible risk factors are addressed, its progression can be halted or slowed.

ECC: cause

Dental caries is a multifactorial disease caused by oral bacteria and mediated by dietary sugars and carbohydrates. It is well established that caries is a dynamic process that can progress or regress, depending on a multitude of variables that can alter the normal balance of demineralization and remineralization. The Featherstone caries balance concept states that the balance of pathologic factors can be altered in favor of protective factors to halt or slow down the caries process. In individuals with active caries, without changes to alter the balance in favor of protective factors over pathologic factors, the caries process continues, with new and recurrent caries resulting.

The mutans streptococci (MS) group of bacteria is most strongly associated with the pathogenic process of ECC. MS adheres to enamel and produces large amounts of acids but it also thrives in the acidic environment it creates. MS can be acquired during early infancy through vertical transmission of bacteria via saliva from the primary adult caregiver to the child. Factors influencing colonization include frequent sugar exposure in infants and habits that allow salivary transfer from mothers to their infants. Maternal factors that increase bacterial transmission to their infants include high levels of MS, poor plaque control, and frequent intake of sugars and carbohydrates.

Children’s risk for caries development and progression is influenced by various social and behavioral factors, including diet, oral hygiene practices, and fluoride exposure. Parents help define oral health practices early in their child’s life and also when to establish regular dental care. Their beliefs and self-efficacy help determine to what extent they engage in oral health-promoting behaviors.

Infant oral health and establishment of a dental home

The American Dental Association (ADA), American Academy of Pediatric Dentistry (AAPD), and American Academy of Pediatrics recommend that all children have their first preventive dental visit and establishment of a dental home by age 1 year. A dental home is defined as an ongoing, comprehensive relationship between the dentist and the patient (and parents), inclusive of all aspects of oral health delivered in a continuously accessible, coordinated, and family-centered way. A dental home should be established such that children can have access to regular dental visits that include caries risk assessment (CRA), anticipatory guidance, and individualized plans to prevent and manage disease, with referral to dental specialists when appropriate.

Preventing ECC is more cost-effective compared with treating advanced caries. An infant oral health visit and establishment of a dental home by age 1 year offer the best opportunity to provide risk-based primary prevention and promote sound oral health practices, which can mitigate a child’s risk of disease over a lifetime.

CRA

An assessment of caries risk during infancy and periodically thereafter allows for early identification and understanding of a child’s current and changing risk factors for ECC. Previous experience of caries is a strong predictor of future caries. Therefore, successfully addressing caries risk factors during early childhood can reduce a lifetime burden of dental disease.

Caries risk factors unique to infants and young children include perinatal considerations, establishment of oral flora and host-defense mechanisms, susceptibility of newly erupted teeth, dietary transition from bottle or breastfeeding to cups, and childhood food preferences. CRA allows for a customized preventive plan to be developed that is appropriate for the child and family.

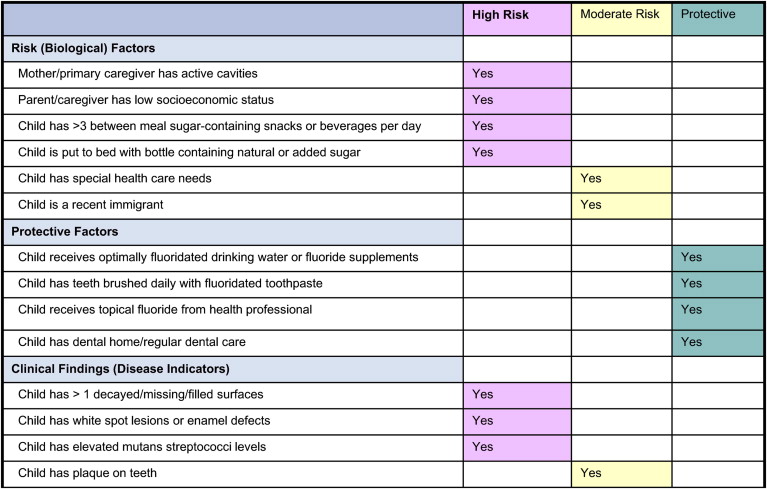

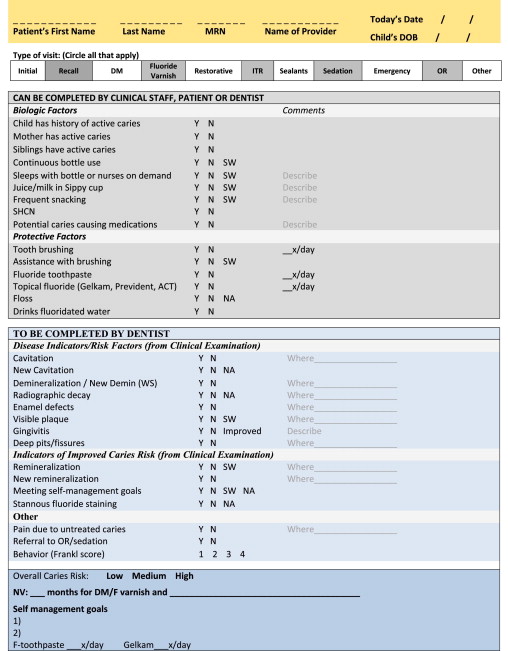

Fig. 1 shows a CRA form adapted from the American Academy of Pediatric Dentistry (AAPD) CRA Form for 0-year-old to 5-year-old children. Fig. 2 shows a CRA tool used by in the ECC Collaborative, a quality improvement initiative funded by the DentaQuest Institute, which is testing the feasibility and effectiveness of a risk-based disease management approach in preschool children with ECC. The ECC Collaborative CRA is an adaptation of the AAPD and pediatric Caries Management by Risk Assessment (CAMBRA) CRA. The progression or reversal of dental caries is determined by the balance between pathologic and protective factors.

Biological risk factors are determined from an interview with the parent and include biological or lifestyle factors that contribute to the development or progression of caries. These factors include a mother with active decay or recently placed restorations, a family of low economic status, a child who frequently consumes snacks and drinks that are high in sugars or carbohydrates, and a child who sleeps with a bottle or sippy cup containing anything other than water. Children with special health care needs (SHCN) may have feeding problems as well as difficulties with food clearance.

Protective factors, also determined during the interview with the parent, include biological or behavioral factors that can improve a child’s caries risk. These factors include assistance with toothbrushing and optimal exposure to fluoride.

Disease indicators are clinical findings from the examination that correlate strongly to disease or to improved caries risk. These indicators include the presence of cavitated lesions, enamel demineralization, enamel defects, presence of heavy plaque (leading to gingival inflammation), and remineralization. Children born prematurely, or with low birth weight, or those with SHCN are at increased risk for enamel defects. Teeth with enamel defects in the presence of poor plaque control and frequent sugar or carbohydrate exposure are at significant risk for ECC.

Based on the distribution of risk factors and protective factors, the health care provider can make a determination of a child’s caries risk, explain the caries process and the causative factors to the parent, and develop in collaboration with the parent self-management goals to prevent or manage their child’s caries risk.

ECC disease prevention and management strategies

Children’s oral health is influenced by various social and behavioral factors, such as diet, oral hygiene practices, and fluoride exposure. It is now accepted that surgical treatment of caries alone does not address the caries process. On the other hand, it is known that caries is preventable and the disease may be halted or slowed down under a favorable balance of conditions. Therefore, risk-based disease management of ECC is based on the assumption that children who initially present as high caries risk may improve their caries risk over time.

Delaying the Transmission of Oral Bacteria in Infants

Preventing and delaying the acquisition and transmission of MS involve reducing the bacteria levels in the mother and other caregivers, modifying saliva-sharing activities, and altering feeding behaviors that promote caries. Mothers and adult caregivers should be encouraged to seek dental care and improve their own oral health, ideally in the prenatal period.

Diet and Nutrition Counseling

Dietary factors and food choices are determinants of dental caries and other chronic conditions. Increased risk of caries is significantly associated with frequent and total consumption of simple sugars. Parents should be counseled on the importance of reducing the frequency of exposure to sugars and refined carbohydrates in foods and drinks. Parents should be recommended to:

- •

Breastfeed their infants

- •

Avoid bottle or sippy cup to bed with anything other than water

- •

Limit sugary foods and drinks, including fruit juices, to mealtimes

- •

Encourage a balanced diet and healthy snacking, such as fruits and vegetables

Oral Hygiene, Use of Fluorides and Other Remineralizing Agents

Because the quality of tooth cleaning is important, young children require assistance with toothbrushing from an adult caregiver, beginning with the first erupted tooth. With correct positioning (such as using a knee-to-knee position with 2 adults or by having an adult approach from behind the child’s head), and retraction of the lips and cheeks, it should take no more than 1 minute to brush a young child’s teeth. Flossing is indicated if there are any contacts between teeth (typically after 3–4 years of age for posterior teeth).

Fluoride toothpaste is an effective, safe, and cost-effective prevention tool for children. The current recommendation by the AAPD is that all children 2 to 5 years of age should use a pea-sized amount of fluoride toothpaste, whereas children younger than age 2 years determined to be medium or high caries risk should use a smear of fluoride toothpaste. In children younger than 2 years, the concern is the risk of mild fluorosis. However, young children are largely at risk for fluorosis when allowed to eat or lick toothpaste. Because ECC is preventable and can be devastating and costly to treat, CRA is most important during infancy and periodically thereafter to ensure that children who would benefit from fluoride toothpaste are recommended by their health professionals to use it.

Drinking fluoridated water is the most convenient and cost-effective way to provide optimal fluoride benefits. In suboptimally fluoridated communities, a fluoride supplement may be prescribed to children with high caries risk as recommended by the ADA.

Professional topical fluoride treatments should be based on CRA. The AAPD and the ADA recommend the following intervals to receive a full-mouth topical fluoride treatment (fluoride varnish):

- •

Every 3 to 6 months for high-risk children

- •

A minimum of every 6 months for moderate-risk children

Low-risk children may not receive additional benefit from topical fluoride treatments in addition to what they receive from fluoridated drinking water and toothpaste. Children with severe ECC and who already have demineralized enamel or cavitated carious lesions may benefit from more frequent professional topical fluoride applications than every 3 months to assist in controlling the caries process.

Other fluoride compounds such as silver diamine fluoride and stannous fluoride may be more effective than sodium fluoride for topical applications. Topical iodine and emerging products such as casein phosphopeptide and calcium phosphate products are available for use in addition to fluorides to assist in controlling and reversing the caries process.

Xylitol

Xylitol is a sugar substitute that is a part of the polyol family, which includes sorbitol, mannitol, and malitol. Xylitol reduces plaque formation and bacterial adherence and inhibits enamel demineralization and MS. Studies have found that xylitol can reduce MS in plaque and saliva and can reduce caries in young children and their mothers, along with decreasing the transmission of MS from mother to child.

In adults, chewing 4 to 10 g of xylitol in chewing gum divided into 3 to 7 times per day is effective in suppressing the bacterial load. Xylitol is now also available in syrups and lozenges. A study found that xylitol syrup (8 g/d) reduced ECC by 50% to 70% in children 15 to 25 months of age. Another study found that gum or lozenges taken by children at 5 g per day resulted in 35% to 60% reduction of caries, with no difference between the delivery methods.

Sealants and Interim Therapeutic Restorations

Any tooth surface with deep pits or grooves benefits from treatment with a bonded or glass ionomer sealant. Typically, permanent molars are candidates for sealants, but primary molars may also benefit from sealant placement, especially if caries has already developed on other primary molars with similar pit and fissure anatomy.

If destruction of tooth structure by the caries process is minimal, arrest of the decay might be possible with remineralization of tooth structure. Restorative treatment may be deferred if the disease can be stabilized.

If decay has progressed mildly into dentin or caries arrest has not been achieved, interim therapeutic restorations (ITR) may be performed to achieve caries control. The ITR procedure involves removal of caries using hand or slow-speed rotary instruments with caution not to expose the pulp. After preparation, the tooth is restored with a fluoride-releasing glass ionomer restorative material. Parents should be advised that this approach is caries control rather than permanent restoration.

Restorative Treatment

When significant tooth structure has been destroyed by the caries process, restorative treatment is performed to restore function or to improve esthetics. Young children who are not cooperative or children with SHCN commonly require pharmacologic management, including the use of nitrous oxide, sedation, or general anesthesia. However, the costs of general anesthesia are high, and rates of recurrent caries after restorative treatment under general anesthesia have been reported in the literature to be 37% to 79% 6 to 12 months after. Therefore, long-term success of restorative treatment is contingent on effective management of the disease responsible for ECC, along with the use of appropriate restorative technique and restorative materials for the primary dentition.

Reevaluation of a child’s caries risk status and compliance with self-management goals provides important information to determine the type of restorations best suited for each patient. A child who shows improved caries risk may receive more conservative restorative treatment. On the other hand, a child showing no improvement of caries risk or worsening clinical caries activity benefits from more aggressive care to reduce caries in susceptible tooth surfaces, such as with stainless steel crowns.

When there is caries arrest, restorative treatment may be deferred, especially in a child unable to cooperate for restorative care. However, close follow-up and preventive care based on caries risk are essential to safeguard from relapse. Seeing a child more frequently for preventive care over time usually reduces a child’s fears and builds trust between the care provider and the child, allowing for restorative treatment to be completed with greater ease in the clinical setting, at a later time.

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses