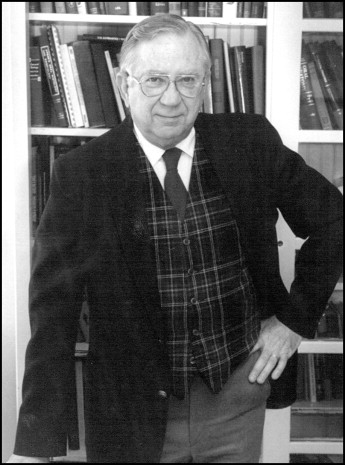

When Don Enlow arrived in Cleveland in 1977 to head the orthodontic department at Case Western Reserve University (CWRU), he began a new chapter in his lifelong interest in human craniofacial growth and development. As a nondentist heading a clinical department, he was in a unique position to help shape the future of dental education. Dr Enlow seized this opportunity to advance the importance of biology in the education of orthodontic residents and dental students alike. In addition to his role as chairman of the orthodontic department (1977-1988), he also served as associate dean for Graduate Studies and Research during this same time period and later was acting dean of the school from 1983 to 1986.

During his tenure at CWRU, Dr Enlow implemented several changes that continue to keep the CWRU dental school at the forefront of dental education. As department chair, he recognized the importance of recruiting orthodontic residents from around the world. His reputation as the expert in facial growth made CWRU an instant destination for bright, ambitious, and adventurous students across North America, Europe, and Asia. Dr Enlow often was quoted as saying, “If we take students from Ohio, we will be known locally; if we take students from across the USA, we will be known nationally; but if we take students from all over the globe, we will be a world leader in dentistry.”

Even after his retirement as department chair in 1989, international recruitment remained a mainstay of the CWRU orthodontic department; Dr Enlow had students from every continent except Antarctica. As associate dean, he was instrumental in shaping the careers of junior faculty. One faculty member, Jerold Goldberg, would go on to be the most influential dean in the history of the school. When asked about Dr Enlow, Goldberg remarked, “Don provided me with my first administrative appointment as chair of oral and maxillofacial surgery, and he also shaped my research career. He showed me how to be an academic dentist. He was a true leader in dental education and will be missed.” The current dean at CWRU, Ken Chance, also was a student of Dr Enlow.

Dr Enlow’s unique contribution to dental education was his ability to entice clinicians in all disciplines to think about biology as the Rosetta Stone of clinical care. Beginning in 1968 with his classic text, The Human Face , Dr Enlow introduced the world to the concepts of remodeling and displacement as the basic biologic processes responsible for growth of the facial skeleton. He meticulously described the remodeling of each cranial bone and the mandible, and he mapped the depository and resorptive areas on each bone. These maps helped clinicians to understand how a child’s face matures into an adult’s face. In addition to the topographic mapping of the face, he pioneered the concept of anatomic compensation, whereby the many facial parts are assembled in unequal but balanced combinations to result in the first molars occluding within 6 mm at the level of the occlusal plane. Modern orthodontics is based in part on his concept of anatomic compensation. As orthodontists, we must identify the areas of compensation in the anteroposterior and vertical dimensions. We then must decide whether to keep or eliminate these compensations based on our treatment goal—to produce a healthy occlusion, an esthetic face, and a beautiful smile.

As a young man, Dr Enlow served in the US Coast Guard in World War II. He earned his BS degree in 1949 from the University of Houston, Texas, and an MA degree from Texas A&M University in College Station in 1951, and began extensive fossil field prospecting all over West Texas. During 1 particular expedition, he found a bone fragment that gave him the idea to make ground sections of fossil bone.

He describes his “aha moment” in the introduction to his most recent book, Essentials of Facial Growth (second edition), as follows. “Well, back at the lab, I did just that. And what I saw just absolutely floored me. I tell you I was just astounded . I remember that my hands were shaking as I stared at that first section for long minutes, almost disbelieving. . . . I could not help but think that what I was seeing was just impossible. After all, I was looking at bone tissue over 200 million years old. . . . Yet I had to believe my eyes. I was seeing something that no one had ever seen. Yes, profoundly exciting. I think it must have been something like an explorer’s feeling when discovering something like a new continent. Big! . . . I had just been on a marvelous lark having a young man’s great time looking for dinosaurs. I did not realize that I had entered, unexpectedly, a long research road which I did not realize could end up with a working understanding of how the vertebrate face, especially the complex human craniofacial assembly, grows and develops.”

Before his arrival in Cleveland, Dr Enlow received his PhD degree in anatomy from Texas A&M University in 1955 and was an assistant professor of biology at West Texas State University in Canyon from 1956 to 1957. In 1958, he moved north to the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor, where he was first an assistant professor and later an associate professor in the School of Medicine. In 1966, he was also named director of the Physical Growth Program at the Center for Human Growth and Development, an interdisciplinary unit founded by the late Robert E. Moyers. He was a prime mover in the program project funded by the National Institutes of Health that enabled many years of craniofacial research using the nonhuman primate model. This continuous funding also led to the publication of numerous papers on normal craniofacial growth and 2 atlases based on data from the University of Michigan Growth Study. In 1972, Dr Enlow moved from Michigan to become the chairman of anatomy at the West Virginia University School of Medicine in Morgantown. He furthered his academic career at that university before he was tapped to head the orthodontic department at CWRU. During his academic career, Dr Enlow authored 8 textbooks on facial growth, wrote 37 chapters on facial growth for other textbooks, and published 75 articles in the peer-reviewed literature.

Although dedicated to his career as a research scientist, Dr Enlow found time to play golf with family and friends at the Shaker Country Club and loved to challenge his students to a competitive match. In his heart, he was a country boy from Texas who collected guns and enjoyed going to the field and the shooting range. He also loved motorcycles. That practice led to one of his most memorable lectures on facial growth: it was delivered with casts on both forearms from an injury sustained while riding the previous day. Dr Enlow was a gifted scientist who changed the world in a positive way. His legacy will live forever in the hands and hearts of the students he taught and the colleagues he mentored.

Dr Enlow is survived by his wife, Martha; daughter, Sharon (Roger) Hack; granddaughters, Lisa (Mark) Tate and Janna (Andy Heidt) Hack; and great-grandchildren, Logan Tate, Michael Tate, Bryce Tate, and Kaia Heidt.

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses