Gingival recession represents a clinical condition in adults frequently encountered in the general dental practice. Clinicians often face dilemmas of whether or not to treat such a condition surgically. An initial condensed literature search was performed using a combination of gingival recession and surgery controlled terms and keywords. An analysis of the search results highlights the limited understanding of the factors that guide the treatment of gingival recession. Understanding the cause, prognosis, and treatment of gingival recession continues to offer many unanswered questions and challenges in periodontics as we strive to provide the best care possible for our patients.

Key points

- •

Gingival recession is defined as when “the location of the gingival margin is apical to the cemento-enamel junction (CEJ).”

- •

About 23% of adults in the United States have one or more tooth surfaces with 3 mm or more gingival recession.

- •

The cause of gingival recession is multifactorial, confounded by poorly defined contributions from predisposing and precipitating factors.

- •

Predisposing factors include bone dehiscence, tooth malposition, thin soft and hard tissues, inadequate keratinized/attached mucosa, and frenum pull.

- •

Precipitating factors include traumatic forces (eg, excessive brushing), habits (eg, smoking, oral piercing), plaque-induced inflammation, and dental treatment (eg, certain types of orthodontic tooth movement, equal/subgingival restorations).

- •

Surgical correction of a gingival recession is often considered when (1) a patient raises a concern about esthetics or tooth hypersensitivity, (2) there is active gingival recession, and (3) orthodontic/restorative treatment will be implemented on a tooth with presence of predisposing factors. The benefits of these treatment approaches are not well supported in current literature relative to alternative approaches with control of possible etiologic factors.

- •

Possible surgical modalities for treating a gingival recession include root coverage or keratinized tissue augmentation.

- •

A root coverage procedure is to augment soft tissues coronal to the gingival margin. Examples include coronally advanced flap with or without a subepithelial connective tissue graft and an allograft.

- •

A keratinized tissue augmentation procedure is to provide qualitative changes to the soft tissues apical to the gingival margin. Examples include a free gingival graft and subepithelial connective tissue graft.

Introduction

Gingival recession is defined as when “the location of the gingival margin is apical to the cemento-enamel junction (CEJ).” It is a common dental condition that affects a large number of patients. A survey of adults ranging from 30 to 90 years of age estimated that 23% of adults in the United States have one or more tooth surfaces with 3 mm or more gingival recession. The prevalence, extent, and severity of gingival recession increased with age, with at least 40% of young adults and up to 88% of older adults having at least 1 site with 1 mm or more of recession ( Table 1 ). Other periodontal (eg, oral hygiene and gingival bleeding) and health parameters (eg, diabetes and alcohol intake) were not associated with the extent of recession.

| Study Reference |

Prevalence (%) | Adult Population Defined by | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|

| 23 | ≥3 mm of recession |

|

|

| 50 | >50 y of age with ≥1 site |

|

|

| 88 | >65 y of age with ≥1 site |

|

|

| 85 | Adults with ≥1 site |

|

|

| 40 | 16–25 y of age |

|

|

| 80 | 36–86 y of age |

Therapeutic options for recessions have been well documented with a high degree of success. Soft-tissue grafting procedures represent one of the most common periodontal surgical procedures performed in the United States, with periodontists performing on average more than 100 of these procedures per year (American Dental Association survey 2005–06). What is not so clear is the cause of this condition, the role of possible causative factors, and the need for treatment. With such a prevalent condition, it is critical to discriminate when to treat these lesions and which types of lesions require surgical treatment. This review examines these questions regarding this common oral condition as well as provides an overview of what is known about gingival recession defects and their treatment.

Introduction

Gingival recession is defined as when “the location of the gingival margin is apical to the cemento-enamel junction (CEJ).” It is a common dental condition that affects a large number of patients. A survey of adults ranging from 30 to 90 years of age estimated that 23% of adults in the United States have one or more tooth surfaces with 3 mm or more gingival recession. The prevalence, extent, and severity of gingival recession increased with age, with at least 40% of young adults and up to 88% of older adults having at least 1 site with 1 mm or more of recession ( Table 1 ). Other periodontal (eg, oral hygiene and gingival bleeding) and health parameters (eg, diabetes and alcohol intake) were not associated with the extent of recession.

| Study Reference |

Prevalence (%) | Adult Population Defined by | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|

| 23 | ≥3 mm of recession |

|

|

| 50 | >50 y of age with ≥1 site |

|

|

| 88 | >65 y of age with ≥1 site |

|

|

| 85 | Adults with ≥1 site |

|

|

| 40 | 16–25 y of age |

|

|

| 80 | 36–86 y of age |

Therapeutic options for recessions have been well documented with a high degree of success. Soft-tissue grafting procedures represent one of the most common periodontal surgical procedures performed in the United States, with periodontists performing on average more than 100 of these procedures per year (American Dental Association survey 2005–06). What is not so clear is the cause of this condition, the role of possible causative factors, and the need for treatment. With such a prevalent condition, it is critical to discriminate when to treat these lesions and which types of lesions require surgical treatment. This review examines these questions regarding this common oral condition as well as provides an overview of what is known about gingival recession defects and their treatment.

Etiology

The cause of gingival recession is multifactorial; therefore, a single factor alone may not necessarily result in the development of gingival recession. Factors associated with gingival recession are broadly categorized into 2 types, predisposing factors and precipitating factors, as summarized in Table 2 . Predisposing factors are mainly variations of developmental morphology that may impose a higher risk of recession, whereas precipitating factors are acquired habits or conditions that introduce gingival recession.

| Predisposing Factors | Precipitating Factors |

|---|---|

|

|

Predisposing Factors

As the alveolar bone supports the overlying soft tissue, conditions that may cause bone dehiscence/fenestration defects are thought to increase the risk of developing gingival recession. Malpositioned teeth, especially facially positioned teeth are likewise thought susceptible to recession over time.

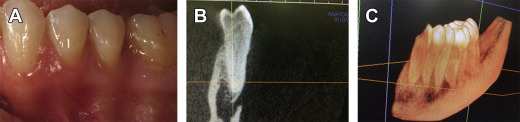

Although it seems obvious that the lack of facial alveolar bone would lead to increased risk of gingival recession, it is not so simple. The prevalence of recession in these studies is not different from the overall prevalence rates for recession. Furthermore, as any practitioner of periodontal surgery can attest, patients frequently have no facial alveolar bone without any signs of recession ( Fig. 1 ). Therefore, although the lack of alveolar bone may be a predisposing factor, there must be other factors that more directly contribute to this type of loss of gingival tissues.

Gingival recession is thought to be more common in patients with thinner gingival tissues than in those with thicker gingival tissues. Facial gingival thickness has been positively associated with its underlying alveolar plate thickness. It seems likely that thinner tissue would be more susceptible to recession than thicker tissue, after nonsurgical or surgical periodontal treatment. Teeth with more prominent roots may have thinner alveolar bone and gingival tissues on the facial aspect creating a predisposing condition for recession, but as with alveolar bone, it is not clear whether lack of tissue thickness alone causes facial recession. Again, with thin gingival tissue as a predisposing factor, recession may develop only in the presence of concurrent precipitating factors, for example, inflammation and trauma. Although unproven, any differences in risk of gingival recession apparent between thin and thick tissue may be due more directly to precipitating factors involved. Without these precipitating factors, the gingival margin with thin tissues or lack of alveolar bone could remain unchanged.

Another factor frequently cited as a predisposing factor leading to gingival recession is a frenum pull. It is thought that when the attachment of the frenum is proximate to the gingival margin, the repeated stretch of the frenum during oral function could exert forces somehow compromising the mucosal tissue margin or oral hygiene in leading to gingival recession. However, cross-sectional studies failed to demonstrate an association of recessions with high frenum attachment.

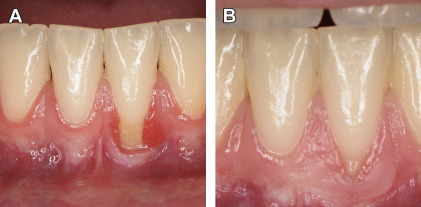

Inadequate keratinized mucosa (KM), most commonly defined as equal or less than 2 mm, is frequently observed concurrently with gingival recession. Historically, it has been considered a predisposing factor of gingival recession. A cross-sectional study established a correlation between inadequate KM and increased gingival inflammation, which is a precursor of periodontal diseases leading to gingival recession. However, inadequate KM might simply be a consequence of gingival recession, rather than a cause of gingival recession. This point is supported by an interventional, longitudinal study that concluded that the attachment level could be maintained with control of gingival inflammation, even without adequate KM. This study with 32 subjects concluded that sites with insufficient attached mucosa (≤2 mm) due to gingival recession did not lose attachment or have additional recession over a period of 6 years. In the presence of inflammation, patients without adequate KM showed continuous attachment loss and additional recession. Therefore, poor oral hygiene may be considered a precipitating factor for gingival recession. However, another split-mouth design study following up 73 subjects for 10 to 27 years found that teeth with recessions without receiving surgical treatment experienced an increase of the recession by 0.7 to 1.0 mm. Further, new recessions developed in 15 sites during the study period in the absence of inflammation. In contrast, teeth with gingival recession receiving a free gingival graft had a reduction of gingival recession by approximately 1.5 mm through creeping attachment. Therefore, although anatomic variants considered to be predisposing factors leading to recession do not always require treatment, with concurrent precipitating factors, surgical intervention may be indicated.

Precipitating Factors

The role of oral hygiene practices as contributing to the occurrence of gingival recession remains a major consideration in the understanding of the cause, the prognosis, and the treatment. It is important to recognize that gingival recession may be associated with both extremes of oral hygiene, one occurring in patients with extremely good oral hygiene and the other in those with unfavorable oral hygiene as described earlier. In the former type, meticulous brushing is thought to introduce trauma to the gingiva leading to recession. This type of recession is commonly seen on the facial side of canines and premolars and associated with overzealous brushing habits. Contrarily, poor oral hygiene is associated with recession due to plaque-induced inflammation and subsequent attachment loss. Although the role of traumatic tooth brushing as a precipitating factor to gingival recession is well accepted, the evidence in support of this concept remains limited. It seems that several factors related to tooth brushing may contribute to recession. These factors include brushing force and brush hardness, frequency and duration of tooth brushing, as well as frequency of changing tooth brushes and the brushing techniques and types of manual or electric brushes used. In cases of both overzealous and insufficient oral hygiene, an underlying inflammatory response is likely to contribute to tissue destruction resulting in gingival recession. Another precipitating factor for recession is alveolar bone and soft-tissue remodeling associated with generalized periodontal disease ( Fig. 2 ) or tooth extraction. This condition commonly occurs in the proximal sites of teeth adjacent to the extraction site and often results in circumferential exposure of root surfaces of involved teeth.

Less commonly found, but clinically important, local gingival tissue trauma or irritation as found with tobacco chewing and oral piercing can lead to inflammatory changes in the tissues resulting in gingival recession. When smokeless tobacco is used, the tobacco is kept in the vestibule adjacent to mandibular incisors or premolars for a prolonged time. The gingival tissues can experience mechanical or chemical injury with the consequence of a recession. In the presence of labial or lingual piercings, gingival recession is found in up to 80% of pierced individuals in mandibular and maxillary teeth. In addition, oral piercing poses a 11-fold greater risk for developing gingival recession.

One frequent concern for gingival recession is with orthodontic tooth movement ( Fig. 3 ). The risk for gingival recession in the mandibular incisors during or after orthodontic therapy is much studied, yet research in this area remains inconclusive. Most commonly, studies have evaluated orthodontic repositioning of the mandibular incisors as proclination, with the forward tipping or bodily movement more likely to lead to thinner alveolar bone and soft tissues on the facial aspect of the tooth, and retroclination, leading to an increased thickness of facial tissues. Studies evaluating the effects of orthodontic treatment on gingival recession typically suggest an incidence of 10% to 20% when evaluated for as long as 5 years after the completion of orthodontic therapy. These rates of occurrence, considered relative to the overall high prevalence found in adults, suggest that orthodontic tooth movement may provide only a minor contribution to the overall prevalence of gingival recession. Two recent studies have taken this discussion a step further in suggesting that the extent of gingival recession when it occurs after orthodontics may be small and of limited clinical concern, affecting only 10% of patients, with most cased being readily treatable as Miller class I lesions. These findings suggest that preorthodontic periodontal procedures directed at minimizing recession may not be justified in most cases. A systematic review of this literature confirmed that, although soft-tissue augmentation as a preorthodontic procedure may be a clinically viable option, this treatment is not based on solid scientific evidence.

Repeated scaling and root planning or periodontal surgeries on shallow pockets may induce clinical attachment loss, partially manifested by gingival recession. It was concluded that the critically probing depth that determines if a certain procedure will gain or lose clinical attachment is 2.9 and 4.2 mm for scaling and root planning and the modified Widman flap procedure, respectively. It is thought that tissue remodeling in sites with shallow pockets during healing following these periodontal procedures may result in minor clinical attachment loss.

Pathogenesis of gingival recession

The loss of clinical attachment is apparent either as increased probing depth or as gingival recession. A preclinical study inducing gingival recession by replacing rat incisors with acrylic resin implants suggested that gingival recession is associated with (1) local inflammation characterized by mononuclear cells, (2) breakdown of connective tissue, and (3) proliferation of the oral and junctional epithelia into the site of connective tissue destruction. The 2 epithelial layers eventually fuse together, encroaching on the intervening connective tissue. The common keratinized layer differentiated and separated, forming a narrow cleft, bringing about a reduction in height of the gingival margin, which is manifest clinically as gingival recession. Thin tissue seems to recede more often in response to inflammation as a result of trauma to the tissues. Human histology from chronic and acute clefts and wide recessions confirms the relevance of an inflammatory infiltrate in the pathogenesis of clefts versus wide recessions. In all subtypes of recessions, the epithelium is acanthotic and proliferative and surrounded by an inflammatory infiltrate. In addition, in acute clefts associated with tooth brushing trauma, necrotic cells can be found. In wide recessions, the dentogingival epithelium penetrates into the lamina propria, thereby decreasing the width of the lamina propria and allowing the dentogingival and oral epithelia to coalesce, resulting in loss of attachment to the tooth. The inflammatory infiltrate can span the entire thickness of the width of the gingiva thus promoting a recession. In thicker gingiva, connective tissue free of inflammatory infiltrate may be interposed between oral and junctional epithelia preventing a recession.

Factors to be considered for treating gingival recession

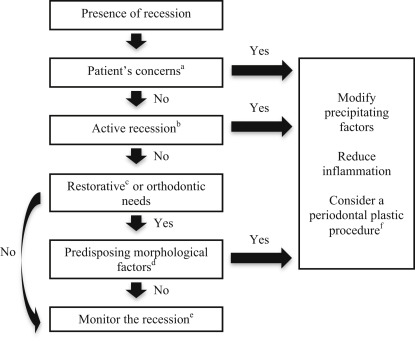

Does gingival recession require surgical treatment? To address the question, the authors first conducted targeted searches in PubMed and Embase to capture a narrow set of studies focused on surgical treatment of gingival recession ( Box 1 ). Reference lists of key studies from this result set were checked for additional studies relevant to the cause, contributing factors of gingival recession, and indications of surgical interventions. Subsequent searches were run in PubMed on themes identified during the initial literature review. An analysis of the search results identified factors that influence the decisions of whether or not to treat gingival recession, based on which a stratified, evidence-based decision-making process ( Fig. 4 ) was formulated. Recessions adjacent to implants were excluded.

(“gingival recession/surgery”[mh] OR (“gingival recession”[majr] OR (“gingival”[ti] AND (“recession”[ti] OR “recessions”[ti]))) AND (“oral surgical procedures”[majr] OR surgery[ti] OR surgeries[ti] OR surgic*[ti] OR operati*[ti])) AND english[la] NOT (animals[mh] NOT humans[mh]) NOT (case reports[pt] OR “case report”[ti]).