Alveolar distraction osteogenesis may offer several advantages over bone grafting alone in the treatment of vertical alveolar defects. No donor site is required; distraction of bone and surrounding soft tissue occurs simultaneously; and the transport segment is a form of pedicled graft that is never separated from its blood supply, maximizing vitality and minimizing resorption. It has the potential for better control of vertical height, esthetics, and biomechanical loading.

Congenital absence of teeth, such as in oligodontia and alveolar clefting, is usually accompanied by bony defects of the maxillary alveolus. Acquired bony defects of the maxillary alveolus result following tooth extraction, periodontal disease, maxillofacial trauma, and tumor ablation. The configuration of alveolar defects can be primarily horizontal or vertical in nature, or a combination of each, and can limit the restoration of missing natural teeth with dental implants.

The treatment of alveolar defects includes guided bone regeneration using a variety of membranes, onlay grafting of autogenous bone, connective tissue grafting, and alloplastic augmentation. Vertical alveolar defects are difficult to overcome in a predictable manner using autogenous bone grafts and often lead to esthetic shortcomings. Distraction osteogenesis of the maxillary alveolus permits correction of alveolar defects, often without the use of a bone graft.

Alveolar distraction osteogenesis (ADO) may offer several advantages over bone grafting alone in the treatment of vertical alveolar defects. No donor site is required; distraction of bone and surrounding soft tissue occurs simultaneously; and the transport segment is a form of pedicled graft that is never separated from its blood supply, maximizing vitality and minimizing resorption. ADO has the potential for better control of vertical height, esthetics, and biomechanical loading.

The following alveolar defect classification has been proposed by Jensen et al:

-

Class I: A vertical defect exists that is up to 5 mm in which there is sufficient bone to distract without bone grafting.

-

Class II: Alveolar defects are present with up to 10 mm of vertical loss in which there is usually significant horizontal loss. Such defects require bone grafting for width before or after distraction.

-

Class III: The defects have more than 10 mm of vertical loss and significant horizontal loss. Bone graft reconstruction of the basal bone is required before a delayed distraction procedure can be performed.

Alveolar distraction devices have three basic components: an upper member, a distraction rod, and a lower member/base plate supporting the vertical force of distraction. These devices can be classified as intraosseous or extraosseous; uni-, bi- or multidirectional; nonresorbable or resorbable (not requiring a second surgery to remove distracter components); and prosthetic (can remain in place to be used to support the dental prosthesis) or nonprosthetic (must be removed following distraction and replaced with a dental implant).

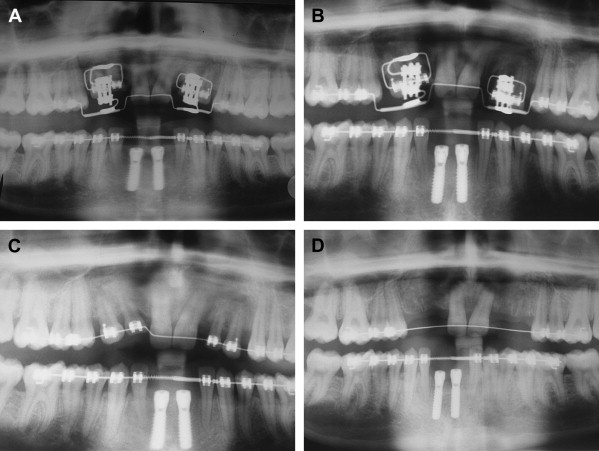

ADO is indicated for the treatment of defects where the alveolar processes are atrophic and deficient. ADO can also be used to correct vertical defects caused by ankylosis and submergence of primary teeth retained in the absence of succedaneous teeth ( Fig. 1 ). ADO is contraindicated in severe atrophy where there is insufficient bone to allow safe hardware placement between tooth roots and the floor of the nose, the maxillary sinus, or the inferior alveolar nerve. It may also be contraindicated in cases of severe osteoporosis where bone quality is poor, or in patients who are unlikely to demonstrate compliance with the rigors of the distraction process. This latter requirement in an adolescent patient may be the most important. ADO is a labor intensive technique with a significant transitional morbidity. Bone grafts may greatly simplify treatment and should always be considered as an alternative in young patients.

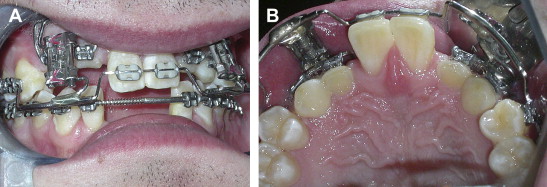

The first step in ADO is to plan the vector of distraction. A distractor is chosen that is capable of delivering a force in the direction of the chosen vector. If teeth are available to anchor a distraction device, an external tooth-borne device can be chosen ( Fig. 2 A, B); otherwise, an internal bone-borne device must be selected. The effect of the rigid palatal tissues and the lingual tissues on the vector of distraction should be kept in mind when distracting the maxilla or mandible. Palatal tissues tend to exert pull on the distracting segment, causing it to tilt lingually away from the desired vector.

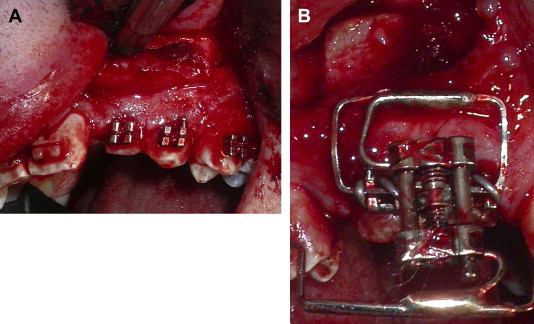

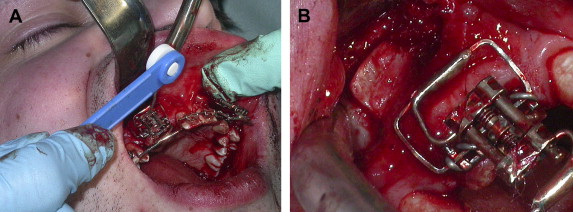

An incision is made in the vestibule or at the crest of the alveolar process, and a mucoperiosteal flap is elevated. Vertical and horizontal osteotomies are performed through the labial or buccal cortical bone of the alveolus using a saw or a fine fissure bur ( Fig. 3 A). The device is then attached to the teeth flanking the partially osteotomized segment ( Fig. 3 B). The osteotomies are then completed by extending the cuts through the palatal cortical bone using osteotomes, and the segment is mobilized ( Fig. 4 A, B) to ensure that there are no bony or dental interferences to unrestricted transport along the selected vector of distraction. The wound is then closed.

After a 5- to 7-day latency period, the segment is distracted once or twice daily at a rate of 0.5 to 1.0 mm per day ( Fig. 5 A, B) until the desired bony position is attained. Overdistraction of the segment by 1 to 2 mm may minimize relapse. A consolidation phase of 6 to 12 weeks with the distractor in place allows undisturbed healing of the distracted bone. If teeth are present in a configuration which, when united by fixed orthodontic appliances, can facilitate stabilization of the segment, the distractor can be removed. Fixed orthodontic appliances should be worn for the duration of the consolidation phase ( Fig. 5 C). At some point following the consolidation phase, all metal distractors must be removed unless they are resorbable. If ankylosed teeth were used for anchorage of the distraction segment, they are extracted following the removal of the distraction hardware ( Fig. 5 D). Dental implants can then be placed into the distracted alveolar segment and restored in their new ideal position ( Fig. 6 A–H).