There are many types of pain conditions that are felt in the orofacial structures. Most of the conditions treated by the dentist are associated with the teeth, periodontal structures, and associated mucosal tissues. This article focuses on the differential diagnosis of other common pain conditions the dentist will likely face, such as temporomandibular disorders, neuropathic pain disorders, and common headaches; and the clinical presentation of each. Controlling or reducing pain can be accomplished by controlling perpetuating factors such as parafunctional habits and by some simple behavioral modifications. Finally, this article offers some simple treatment considerations.

The focus of this article is on the differential diagnosis of pain disorders that typically fall outside the realm of dental diseases. There are a great variety of such conditions—too many to review here. Therefore, this article discusses the differential diagnosis of a few of the more common orofacial pain conditions the dentist may face in a practice. These conditions are divided into two sections: temporomandibular disorders (TMD) and other common orofacial pain disorders. The first section reviews common TMD that are the responsibility of the dentist to identify and manage. The second section reviews some common orofacial pain disorders that the dentist needs to recognize but for which the dentist may not be the primary care provider.

TMD

TMD is a collective term that includes a number of clinical complaints involving the muscles of mastication, the temporomandibular joint (TMJ), or associated orofacial structures. TMD are a major cause of nondental pain in the orofacial region and are considered a subclassification of musculoskeletal disorders. In many TMD patients the most common complaint originates from the muscles of mastication rather than from the TMJ. Therefore, the terms TMJ dysfunction or TMJ disorder are inappropriate for many complaints arising from the masticatory structures. It is for this reason that the American Dental Association adopted the term “temporomandibular disorder.”

Signs and symptoms associated with TMD are a common source of chronic pain complaints in the head and orofacial structures. These complaints can be associated with some generalized musculoskeletal problems and even somatization, anxiety, and depression. The primary signs and symptoms associated with TMD originate from the masticatory structures and, therefore, are associated with jaw function. Patients often report pain in the preauricular areas, face, or temples. Reports of pain during mouth opening or chewing are common. Some individuals may even report difficulty speaking or singing. TMJ sounds are also frequent complaints and maybe described as clicking, popping, grating, or crepitus. In many instances, the joint sounds are not accompanied by pain or dysfunction, and are merely a nuisance to the patient. However, on occasion, joint sounds may be associated with locking of the jaw during opening or closing, or with pain. Patients may even report a sudden change in their bite coincident with the onset of the painful condition.

It is important to appreciate that pain associated with most TMD is increased with jaw function. Because this is a condition of the musculoskeletal structures, function of these structures generally increases the pain. When a patient’s pain complaint is not influenced by jaw function, other sources of (orofacial) pain should be suspected.

TMD can be subdivided into two broad categories related to their primary source of pain and dysfunction: masticatory muscle disorders and intracapsular (TMJ) disorders. A description of the most common disorders in each category is reviewed below. A more complete review of TMD can be found elsewhere.

Masticatory Muscle Disorders

Definition

Functional disorders of masticatory muscles are probably the most common TMD complaint of patients seeking treatment in the dental office. With regard to pain, they are second only to odontalgia (ie, tooth or periodontal pain) in terms of frequency. They are generally grouped in a large category known as masticatory muscle disorders.

Clinical features

The two major symptoms of functional TMD problems are pain and dysfunction. Certainly the most common complaint of patients with masticatory muscle disorders is muscle pain, which may range from slight tenderness to extreme discomfort. Pain felt in muscle tissue is called myalgia. The pain is commonly described in terms such as dull, achy, or tender. The symptoms are often associated with a feeling of muscle fatigue and tightness. Patients will usually describe the location of the pain as broad or diffuse, and the pain is often bilateral. This complaint is quite different than the specific location reported in intracapsular disorders.

The severity of muscle pain is generally directly related to the amount of functional activity. Therefore, patients often report that the pain affects their ability to open their mouth, chew, and speak. If the patient does not report an increase in pain associated with jaw function, the disorder is not likely related to a masticatory muscle problem and other diagnoses should be considered.

The clinician should appreciate that not all muscle pain is the same. Some patients suffer with relatively simple overuse muscle pain called “local muscle soreness.” Clinically, the local muscle soreness manifests as tenderness or pain on palpation. Other patients may experience a more regional muscle condition such as myofascial pain. Clinically, myofascial pain is characterized by the presence of localized, firm, hypersensitive bands of muscle tissue called trigger points. These areas create a source of deep pain input that can lead to central excitatory effects resulting in pain referral. This condition manifests as pain on palpation with referral of pain in the surrounding or remote tissues. Sometimes these remote tissues can be teeth, and the primary complaint that the patient may have is tooth pain. It is important that the dentist realizes that the site of pain is not always the same as the source of the pain. In this hypothetical case of myofascial pain, there is nothing wrong with the teeth (the site of the pain); however, it would be easy for the dentist to miss the correct diagnosis if the muscles of mastication (the source of the pain) were not included in the diagnostic work-up. It is also important to realize that myofascial pain originating from cervical muscles may refer pain into the orofacial region. Treating the site of pain in these instances would not result in improvement of the symptoms.

Dysfunction is a common clinical symptom associated with masticatory muscle disorders. Clinically, this may be seen as a decrease in the range of mandibular movement. When muscle tissues have been compromised by overuse, any contraction or stretching increases the pain. Therefore, to maintain comfort, the patient restricts movement within a range that does not increase pain. The restriction may be at any degree of opening depending on where discomfort is felt. The restriction may also be partly due to contraction of the antagonistic muscles, a phenomenon that is called protective cocontraction. In many myalgic disorders the patient is able to slowly open wider but this increases the pain.

Acute malocclusion is another condition that is often associated with masticatory muscle pain. Acute malocclusion refers to any sudden change in the occlusal position that has been created by a disorder. An acute malocclusion may result from a sudden change in the resting length of a muscle that controls jaw position. When this occurs the patient describes a change in the occlusal contacts of the teeth. The mandibular position and resultant alteration in occlusal relationships depend on the muscles involved. For example, the malocclusion associated with slight functional shortening of the inferior lateral pterygoid is clinically evident as disclusion of the posterior teeth on the ipsilateral side and premature contact of the anterior teeth (especially the canines) on the contralateral side. With functional shortening of the elevator muscles (clinically a less detectable acute malocclusion), the patient will generally complain of a sensation of heavier tooth contact on the ipsilateral side. It is important to realize that an acute malocclusion is the result of the muscle disorder and not the cause. Therefore, treatment should never be directed toward correcting the malocclusion by means of occlusal adjustments. Rather, it should be aimed at eliminating the muscle disorder. When the muscle disorder is resolved, the occlusal condition will return to normal.

Etiologic considerations

Myalgia can arise from a number of different causes. The most common cause is an increased level of muscle use. Although the exact origin of this type of muscle pain is debated, some investigators suggest it is related to vasoconstriction of the relevant nutrient arteries and the accumulation of metabolic waste products in the muscle tissues. Within the ischemic area of the muscle certain algogenic substances (eg, bradykinins, prostaglandins) are released, causing muscle pain.

Increased muscle use maybe the result of activities that are outside the normal functional activities of chewing, swallowing, and speaking. Such activities are considered parafunctional and these activities are more likely to compromise the muscle tissues and create pain. Activities such as daytime clenching of the teeth or sleep-related bruxing are common parafunctions that may lead to muscle pain. In addition to clenching and bruxing, habits such as chewing gum and biting lips, cheeks, and finger nails are also considered to be parafunctional activities. It should be appreciated that these activities are very common and do not lead to pain in most individuals.

A misunderstood but very important concept for the clinician to appreciate is the fact that masticatory muscle pain is not strongly correlated with increased muscle activity such as in spasm. In fact, studies reveal that the resting activity of the masticatory muscles as measured by electromyography of patients with chronic muscle pain is no different than that of asymptomatic controls. Therefore the majority of masticatory muscle pain patients are not experiencing spasms.

It is now appreciated that muscle pain can be influenced and actually initiated by the central nervous system through antidromic effects leading to neurogenic inflammation in the peripheral structures. When these peripheral structures are muscles, this is clinically felt as muscle pain. This type of muscle pain is referred to as “centrally mediated myalgia” and can be a difficult problem to manage for the dentist since the peripheral structures, such as teeth, jaw, and muscles are not the significant cause of the pain. In these instances, the central mechanisms need to be addressed, which cannot be accomplished by classic dental therapies. Owing to the involvement of central mechanisms, increased levels of emotional stress and other sources of deep pain may likely influence masticatory muscle pain disorders.

Management considerations

A detailed description of the management of each of the conditions is not the goal of this article and, therefore, other sources should be consulted. However, because some simple behavior modifications may reduce parafunctional use of the muscles, a few first-tier management options are described in this section. Making the patient aware that his or her maxillary and mandibular teeth should not be touching each other except to speak, chew, or swallow is an important first step. In addition, for most masticatory muscle conditions, soft diet, rest, moist heat, and (possibly) nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDS) are usually helpful. Teaching the patient to keep the teeth apart and the mouth relaxed when the jaw is not used is very beneficial if not crucial in reducing pain. If sleep-related bruxism is suspected, a stabilization appliance may be helpful.

TMJ

Definition

The signs associated with functional disorders of the TMJ are probably the most common findings when examining a patient for masticatory dysfunction. Many of these signs do not produce painful symptoms and, therefore, the patient may not seek treatment. When present, however, they generally fall into three broad categories: derangements of the condyle-disc complex, structural incompatibility of the articular surfaces, and inflammatory joint disorders. The first two categories have been collectively referred to as disc-interference disorders. The term disc-interference disorder was first introduced by Welden Bell to describe a category of functional disorders that arises from problems with the condyle-disc complex. Some of these problems are due to a derangement or alteration of the attachment of the disc to the condyle; others to an incompatibility between the articular surfaces of the condyle, disc, and fossa; still others to the fact that relatively normal structures have been extended beyond their normal range of movement. With time, inflammatory disorders can arise from a localized response of the TMJ tissues to loading or trauma. These disorders are often the result of chronic or progressive disc derangement disorders.

Clinical features

The two major symptoms of functional TMJ problems are pain and dysfunction. Joint pain can arise from healthy joint structures that are mechanically abused during function, from impingement of tissues, or from structures that have become inflamed. Pain originating from healthy structures or impingements is felt as sharp, sudden, and (sometimes) intense pain that is closely associated with joint movement. When the joint is rested, the pain resolves instantly. The patient often reports the pain as being localized to the preauricular area. If the joint structures have become inflamed, the pain is reported as constantly dull or throbbing, even at rest, yet accentuated by joint movement.

Dysfunction is common with functional disorders of the TMJ. Usually it presents as a disruption of the normal condyle-disc movement often with the production of joint sounds. The joint sounds may be a single event of short duration known as a click. If this is loud, it may be referred to as a pop. Crepitation is a multiple, rough, gravel-like sound described as grating or grinding. Dysfunction of the TMJ may also present as catching sensations when the mouth is opened. Sometimes the jaw can actually lock. Dysfunction of the TMJ is always directly related to jaw movement.

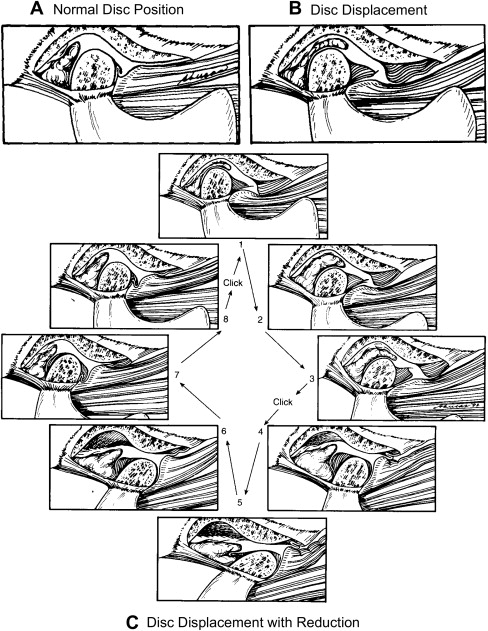

A single click during opening of the mouth is often associated with an anterior displaced disc that is returned to a more normal position during the opening movement. This condition is referred to as a “disc displacement with reduction.” Often when the patient closes the mouth a second click is felt which represents the re-displacement of the disc to the anterior displaced position ( Fig. 1 ). This single opening click associated with disc displacement with reduction should be fairly repeatable. When the patient reports a single, loud, popping or cracking sound that cannot be easily repeated, the clinician should think about the possibility of an adherence. An adherence can occur as a result of prolonged static loading of the joint. In such a case, the lubrication is squeezed out of the contacting joint surfaces and this causes the surfaces stick together. On opening, this union can be disrupted and normal mouth opening resumes.