-

Chapter Outline

Learning Objectives

After reading this chapter, the student should be able to:

- 1.

Recognize that diagnosis of and treatment planning for pulpal and periapical conditions should be part of a broader examination and treatment plan.

- 2.

Integrate the endodontic diagnosis and treatment plan into an overall treatment plan.

- 3.

Understand the importance of the medical and dental history to endodontic diagnosis.

- 4.

Address the correct questions regarding the history and symptoms of the present complaint.

- 5.

Describe clearly to the patient the diagnostic procedure to be followed.

- 6.

Conduct an intraoral examination of both soft and hard tissues that focuses on determining the pulpal and periapical health.

- 7.

Apply, interpret, and understand the limitations of vitality tests.

- 8.

Know when and how to use special approaches, such as a test cavity, and selective anesthesia.

- 9.

Interpret diagnostic radiographs.

- 10.

Understand the mechanisms of pain and how variable the pain experience can be.

- 11.

Understand and detect when pain is referred and when hyperalgesia and allodynia are present.

- 12.

Consolidate all data from the history, symptoms, examination, and tests to form a diagnosis of pulpal and periapical conditions, using appropriate terminology.

- 13.

Identify conditions for which root canal treatment is indicated and contraindicated.

- 14.

Recognize the indications for adjunctive treatments, such as vital pulp therapy, bleaching, root amputation, endodontic surgery, intentional replantation, autotransplantation, hemisection, apexification, orthodontic extrusion, and retreatment.

- 15.

Identify problems that require treatment modifications, such as operative complications, cracked tooth, periodontal problems, isolation difficulties, restorability, strategic value, patient management, medical complications, abnormal root or pulp anatomy, impact trauma, and restricted opening.

- 16.

Design an endodontic treatment plan that is integrated into the overall treatment plan.

- 17.

Present the patient with the preferred treatment plan and any alternatives and explain its development from diagnostic data.

- 18.

Discuss the prognosis of any suggested treatment.

- 19.

Classify potential complications of endodontic procedures.

- 20.

Identify which procedures are ordinarily not within the graduating dentist’s realm of training or experience and which patients should be considered for referral.

- 21.

Recognize the various ways endodontic pathosis and systemic disease interact and also some of the mechanisms of such interactions.

- 22.

Identify the effects of diabetes mellitus, smoking, genetic predisposition, irradiation, sickle cell disease, and viral infections on the pathogenesis of endodontic pathosis and endodontic treatment outcomes.

- 23.

Determine the potential for acute and chronic endodontic infections to cause or contribute to systemic disease, including cardiovascular disease.

Learning Objectives

After reading this chapter, the student should be able to:

- 1.

Recognize that diagnosis of and treatment planning for pulpal and periapical conditions should be part of a broader examination and treatment plan.

- 2.

Integrate the endodontic diagnosis and treatment plan into an overall treatment plan.

- 3.

Understand the importance of the medical and dental history to endodontic diagnosis.

- 4.

Address the correct questions regarding the history and symptoms of the present complaint.

- 5.

Describe clearly to the patient the diagnostic procedure to be followed.

- 6.

Conduct an intraoral examination of both soft and hard tissues that focuses on determining the pulpal and periapical health.

- 7.

Apply, interpret, and understand the limitations of vitality tests.

- 8.

Know when and how to use special approaches, such as a test cavity, and selective anesthesia.

- 9.

Interpret diagnostic radiographs.

- 10.

Understand the mechanisms of pain and how variable the pain experience can be.

- 11.

Understand and detect when pain is referred and when hyperalgesia and allodynia are present.

- 12.

Consolidate all data from the history, symptoms, examination, and tests to form a diagnosis of pulpal and periapical conditions, using appropriate terminology.

- 13.

Identify conditions for which root canal treatment is indicated and contraindicated.

- 14.

Recognize the indications for adjunctive treatments, such as vital pulp therapy, bleaching, root amputation, endodontic surgery, intentional replantation, autotransplantation, hemisection, apexification, orthodontic extrusion, and retreatment.

- 15.

Identify problems that require treatment modifications, such as operative complications, cracked tooth, periodontal problems, isolation difficulties, restorability, strategic value, patient management, medical complications, abnormal root or pulp anatomy, impact trauma, and restricted opening.

- 16.

Design an endodontic treatment plan that is integrated into the overall treatment plan.

- 17.

Present the patient with the preferred treatment plan and any alternatives and explain its development from diagnostic data.

- 18.

Discuss the prognosis of any suggested treatment.

- 19.

Classify potential complications of endodontic procedures.

- 20.

Identify which procedures are ordinarily not within the graduating dentist’s realm of training or experience and which patients should be considered for referral.

- 21.

Recognize the various ways endodontic pathosis and systemic disease interact and also some of the mechanisms of such interactions.

- 22.

Identify the effects of diabetes mellitus, smoking, genetic predisposition, irradiation, sickle cell disease, and viral infections on the pathogenesis of endodontic pathosis and endodontic treatment outcomes.

- 23.

Determine the potential for acute and chronic endodontic infections to cause or contribute to systemic disease, including cardiovascular disease.

Diagnosis

Chief Complaint

The chief complaint is the first information obtained and is usually volunteered by the patient. Patients express their complaint in their own words, which should be recorded in the chart as such. This, after all, is why the patient seeks treatment, and the patient will judge the outcome of treatment by whether the problem, as he or she saw it, was managed. To gain the patient’s confidence, the clinician must pay attention to the chief complaint. When this confidence has been achieved, the patient will be able understand that diagnosis requires a thorough and methodical approach, and he or she can cooperate in this approach.

Importantly, there are many facial pains are not of odontogenic origin. These may be easily confused with tooth pain by both the patient and the dentist.

Health History

Health and Medical History

Whether the patient is returning to the practice or has filled out a new health questionnaire, the medical history is reviewed with the patient directly; this is recorded in the clinical record. Patients who seek and require endodontic treatment are older, on average, and have a higher incidence and more complex profile of systemic medical problems. Some conditions are of concern in diagnosing endodontic problems. For example, acute respiratory infections, particularly of the maxillary sinus, often produce toothache-like symptoms. Stress commonly leads to neuromuscular pain in the masticatory apparatus, with a presentation that includes tooth pain.

Although no medical conditions contraindicate endodontic treatment, there are some conditions that can reduce the patient’s ability to respond to treatment. Acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS) clearly compromises the immune system, as may hepatitis. Drugs used to prevent the rejection of transplants and grafts, in addition to those used to combat glucocorticosteroid deficiency and serious allergies, may have a similar effect. The incidence of type II diabetes is increasing rapidly in the general population and may affect the pathogenesis or healing of endodontic pathosis (see below, Diabetes Mellitus). Patients with active ischemic heart disease may need special consideration, which should be based on a consultation with their cardiologist.

Other factors related to therapeutics may complicate diagnosis. Bisphosphonates are a factor to consider in diagnosis and treatment planning (this is discussed under systemic considerations).

A more frequent concern is that patients who have experienced pain and/or swelling may already be taking antibiotics and analgesics that can mask signs and symptoms.

Antibiotic Prophylaxis

In 2007 an update on the guidelines for antibiotic prophylaxis was released by a task force of the American Heart Association, with input from the American Dental Association. These recommendations greatly reduce the indications for coverage to a limited number of cardiac conditions, which include (1) artificial heart valve, (2) previous history of infective endocarditis, (3) incomplete or repaired congenital heart tissue repair, and (4) some heart transplants. In these patients, the regimen is 2 g of amoxicillin given 30 to 60 minutes before surgery for adults. The dosage for children is 50 mg/kg. For allergic patients, a good choice is clindamycin 600 mg 30 to 60 minutes before the procedure.

The American Association of Orthopedic Surgeons, in conjunction with the American Dental Association, recently updated the guidelines for prophylaxis in joint replacement patients. Patients considered to be at risk include those who have had joint replacements within the past year, particularly those who are immunocompromised or immunosuppressed, those with hemophilia or insulin-dependent diabetes, and those who have had previous joint prosthesis infections. The most recent guidelines state that there is no evidence that dental procedures are directly responsible for instances of artificial joint infections, that local oral antimicrobials should be considered in the prevention of periprosthetic joint infections, and that good oral hygiene measures should be maintained. If antibiotics are indeed indicated, the same regimen is recommended as for cardiac patients.

Endodontic procedures considered to be a risk in patients with cardiac conditions or joint prostheses include instrumentation beyond the apex, periapical surgery, or other procedures that may produce bleeding, such as aggressive rubber dam placement or incision for drainage.

Dental History

Endodontic problems usually have a history ( Fig. 5.2 ). Recent trauma is obviously relevant, as are recent restorations and previous treatment for temporomandibular dysfunction. A longer overview may indicate the type of treatment that would be most appropriate. A patient with a poorly maintained dentition and several missing teeth may not be an ideal candidate for endodontic treatment and subsequent restorative procedures.

History of the Present Complaint

After the patient has explained why he or she is seeking care (and this has been recorded in the patient’s own words), details must be established through methodical questioning. There are a limited number of complaints of endodontic consequence. The patient may have more than one complaint. Pain and swelling, for example, often occur together. The most common complaints are as follows:

- ▪

Pain

- ▪

Swelling

- ▪

Broken tooth

- ▪

Loose tooth

- ▪

Tooth discoloration

- ▪

Bad taste

If there are two or more concurrent complaints, such as pain and swelling, then the history of each complaint must be obtained.

Pain is the most obvious and most important. Understanding the physiology of pain and the anatomy of nociceptive pathways is essential to the diagnosis and treatment of painful conditions. A brief synopsis of pain mechanisms is presented here. Boxes 5.1 and 5.2 present the key elements in list form.

- ▪

An unpleasant sensory and emotional experience associated with actual or potential tissue damage or described in terms of such damage.

- ▪

A dedicated “pain system” includes nociceptors (receptors preferentially sensitive to a noxious stimulus), small-diameter fibers, tracts, and central processing areas.

- ▪

Noxious stimuli activate nociceptors, but this activation does not inevitably result in pain.

- ▪

Activity in pain pathways can be modulated upward or downward, both peripherally and centrally. In particular, descending opioid influences can facilitate or impede the transmission of activity from first-order neurons to higher centers, thus reducing the pain experience.

- ▪

Affective, motivational, and cultural factors contribute substantially to the pain experience.

- ▪

Hyperalgesia (an increased response to a stimulus that is normally painful), allodynia (pain from a stimulus that does not normally provoke pain), and spontaneous pain (pain without a stimulus) result from both peripheral and central changes after inflammation or injury. Central changes may persist after peripheral injury has resolved.

- ▪

Pain may be acute or chronic. Acute pain arises from inflammation or injury to the pulp and periapex. Acute pain is protective. It leads to avoidance and escape to prevent or minimize tissue damage. When it continues, it forces an injured area to be rested. Chronic pain is nonprotective. It may continue long after an injury has healed or may not be associated with an injury. Trigeminal neuralgia and long-term pain of unknown origin are types of chronic pain.

- ▪

Prolonged nociceptive input leads to functional alterations in the subnucleus caudalis, the spinal dorsal horn, and probably the thalamus.

- ▪

Lower thresholds (hyperalgesia)

- ▪

Wider receptive fields

- ▪

Spontaneous activity

- ▪

Recruitment of nonpain fibers (allodynia)

- ▪

A major change is the up-regulation of N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) receptors on the second-order neuron.

Pain is a multifactorial experience subject to modulation. The basic mechanism of nociception is well established. The pulp is innervated largely by nociceptive fibers, either Aδ (fast conducting; sharp pain) or C fibers (slow conducting; dull, throbbing pain). During inflammation, the C fibers dominate, and pulpal pain is characteristically dull, throbbing, and poorly localized. The periodontal ligament (PDL) has a much greater large-fiber innervation than does the pulp, and many of these fibers are mechanosensitive, which explains why pain from the tooth is more easily localized when inflammation has spread into the supporting tissues. First-order nociceptive fibers connect with second-order neurons in the dorsal horn of grey matter in the spinal cord or in its equivalent in the brainstem, the subnucleus caudalis of the trigeminal system. This is a key relay; it is here that much of the modulation of pain takes place. Through endogenous opioid mechanisms, descending tracts from midbrain areas can reduce or prevent the activity from traveling further centrally. The degree to which this mechanism is involved is variable, but much of the affective/motivational component of the pain experience is explained by descending modulation. This explains why similar levels of tissue damage may be related to very different levels of pain.

Sustained and continuous noxious input may cause changes in the second-order neurons, reducing their threshold and increasing their receptive fields. These are elements of central sensitization, a group of changes that contribute to the presentation of long-term and chronic pain (see Box 5.2 ). Central sensitization explains the nature of hyperalgesia, allodynia, and spontaneous pain. Once sensitized, these second-order neurons may be activated by inputs from multiple areas converging on them; this is the phenomenon of referred pain ( Box 5.3 ).

- ▪

Common occurrence

- ▪

Never crosses the midline

- ▪

Can be referred from other teeth or extraoral structures

- ▪

Anesthetizing the true origin reduces or eliminates the pain.

With referred pain, the pain originating in a tooth can seem to come from another tooth or another area, even outside the mouth. It also allows teeth to appear painful when the true origin of the pain is in another tooth, in the neuromuscular system ( Box 5.4 ), in the upper respiratory tract, or even in cardiac muscle.

Complaint

Moderately severe but continuous dull ache in left lower jaw

History

The pain has lasted several weeks and is most severe in the morning. It is not intensified by hot and cold stimuli and is relieved temporarily by mild analgesics. A three-unit mandibular-posterior bridge had been placed a few months earlier. There was neither recent acute infection nor trauma. The referring dentist had completed root canal treatment on the premolar abutment with no change in symptoms.

Examination

No visible or palpable intraoral soft tissue abnormalities are present. All teeth on the left side respond within normal limits to vitality tests and percussion. Radiographs show no lesions in mineralized tissues. Discomfort is not relieved by an inferior alveolar nerve block. Palpation of the left masseter muscle shows it to be acutely tender, particularly on the anterior border. Occlusal examination shows imbalances and premature contacts on the left side. Injecting a local anesthetic into the tender region of the muscle relieves the pain.

Diagnosis

Acute myofascial pain in the left masseter muscle after dental treatment

Etiology

Afferents from the muscle (probably in tendons or fascia) converge on the same second-order neuron in the brainstem trigeminal nucleus as periodontal afferents from the mandibular abutment teeth. The higher centers to which the second-order neuron projects are unable to differentiate between the two inputs. The higher nerve centers “assume” that the new input (from the muscle) originates from the same site as the original input (the teeth).

When neurons from several teeth or other structures converge on a second-order neuron that is sensitized, non-nociceptive levels of activity from these structures may induce firing and activity in the higher levels of the pain system. The higher centers may then identify this as painful activity in these areas. The reverse is also true. For example, painful input from the maxillary sinus may seem to originate from a tooth ( Box 5.5 ).

- ▪

Patient cannot localize the pain, or the site seems to vary.

- ▪

No local dental cause for the pain can be identified.

- ▪

Pain is spontaneous or intermittent and not necessarily related to an initiating stimulus.

- ▪

Stimulation of a suspected tooth does not reproduce the symptoms.

- ▪

A suspected tooth shows no clear etiology (caries, fracture).

- ▪

More than one tooth seems to be involved.

- ▪

Symptoms are bilateral.

- ▪

Selective anesthesia fails to localize the source of pain.

The Pain Referral Phenomenon

The pain referral phenomenon must be taken into account when making a diagnosis. The identification and location of an injured tooth should be straightforward in the early stages of the injury, when activity in nociceptors predominates. Identification of the source is more complex in the longer term, when modulation can modify the presentation by the referral of pain ( Box 5.6 ).

Complaint

A 45-year-old woman was seen with a continuous, moderate, dull, and occasionally severe ache from bilateral temporomandibular joints and molars. Discomfort began with the onset of marital problems and financial hardship. Root canal treatment of a molar provided temporary relief, as did occlusal splint therapy and pharmacologic treatment for depression. However, the discomfort returned.

Examination

Clinical and radiographic examinations of teeth show no abnormalities. Treatment appears successful. Palpation of the temporomandibular joints reveals no abnormality. Further questioning reveals extended emotional stress after marital break-up.

Diagnosis

Orofacial pain of psychogenic origin (tentative)

Etiology

Pain originates from higher nerve centers and is probably entirely affective. Various forms of treatment are only transiently effective, because they affect higher central nervous system centers.

Treatment

Long-term relief depends on removal of the emotional problems sustaining the central nervous system changes or on the patient adopting suppressive strategies. A careful, nonjudgmental explanation of psychogenic pain was given to the patient. In particular, the contribution of both organic and psychological components to the pain experience was described. Clearly, the patient was experiencing pain, but because no organic cause was evident, interventional dental treatment would not bring long-term relief. The prescription of antidepressants by a physician is virtually always a component of treatment.

When pain is one of the complaints, the following questions should be asked:

- 1.

When did the pain begin?

- 2.

Where is the pain located?

- 3.

Is the pain always in the same place?

- 4.

What is the character of the pain (short, sharp, long lasting, dull, throbbing, continuous, occasional)?

- 5.

Does the pain prevent sleeping or working?

- 6.

Is the pain worse in the morning?

- 7.

Is the pain worse when you lie down?

- 8.

Did or does anything initiate the pain (trauma, biting)?

- 9.

Once initiated, how long does the pain last?

- 10.

Is the pain continuous, spontaneous, or intermittent?

- 11.

Does anything make the pain worse (hot, cold, biting)? Does anything make the pain better (cold, analgesics)?

It is also frequently useful to ask the patient to quantify the amount of pain on a scale of 0 to 10, with 0 being no pain and 10 being the most excruciating pain imaginable. This quantification not only gives the practitioner an idea about the urgency and severity of the problem, but also allows comparison of the pain from visit to visit, particularly if there is residual pain after treatment.

If the complaint is swelling or includes swelling, there is a similar list of questions:

- 1.

When did the swelling begin?

- 2.

How quickly has the swelling increased in size?

- 3.

Where is the swelling located?

- 4.

What is the nature of the swelling (soft, hard, tender)?

- 5.

Is there drainage from the swelling?

- 6.

Is the swelling associated with a loose or tender tooth?

If a fractured tooth is part of the complaint, the time and nature of the trauma should be determined, particularly whether other teeth were involved in the trauma even though they were not visibly damaged. Was there any injury to the lips or gingiva? Similarly, with a loose or discolored tooth, the time when it was first noticed should be recorded, along with the history of any trauma that might be involved and whether the tooth was recently restored. A bad taste can result from a number of causes but often is from purulence draining through a sinus tract from a chronic periapical or periodontal abscess.

After thorough questioning that elicits reliable answers, the clinician should be able to generate a tentative diagnosis from the history. This is really a hypothesis that the objective component of the examination will test. The astute clinician’s mind remains open to other possibilities.

Nonodontogenic Pain

Pain in the lower face, particularly in the regions of the jaws, is commonly believed by both the patient and the dentist to be tooth related. Furthermore, the assumption is often that there is significant pulp and/or periapical pathosis that requires root canal treatment. Thus, the first approach is to try to identify an offending tooth with the idea that treatment is required. Frequently, this is not the case. In fact, often this pain is neither odontogenic nor related to any oral tissues. Furthermore, there may be no pathosis or any identifiable etiology. These pains often are inconsistent with nerve patterns and “wander” to different structures; they have different descriptors, such as atypical facial pain, nonodontogenic toothache, atypical odontalgia, persistent dental pain, and psychogenic pain. Unfortunately, attempts to try to resolve these pains with local treatment or even with analgesics are unsuccessful; the pain persists, much to the distress of both the patient and the dentist. When patients present with these unusual pain patterns, the generalist should consider referral to an endodontist, who rules in or rules out an endodontic etiology (see Chapter 6 ). Often, these patients are further referred to a dental pain clinic or to a neurologist, who examines the patient for neurologic disorders.

Objective Examination

Extraoral and intraoral tissues are examined, tested, and compared with other teeth and soft tissues for pathosis.

Extraoral Examination

General appearance, skin tone, facial asymmetry, swelling, discoloration, redness, extraoral scars or sinus tracts, and lymphadenopathy are indicators of physical status. A careful extraoral examination helps to identify the cause of the patient’s complaint and also the presence and extent of an inflammatory reaction in the oral cavity or even at an extraoral site ( Fig. 5.3 ).

Intraoral Examination

Soft Tissue

Soft tissue examination includes a thorough visual, digital, and probing examination of the lips, oral mucosa, cheeks, tongue, periodontium, palate, and muscles. These tissues are evaluated, and abnormalities are noted. Alveolar mucosa and attached gingiva are examined for the presence of discoloration, inflammation, ulceration, and sinus tract formation. Sinus tracts are common. A stoma (parulis) usually indicates the presence of a necrotic pulp and chronic apical abscess ( Fig. 5.4 ) and sometimes a periodontal abscess. Gutta-percha placed in the sinus tract occasionally assists in tactile and radiographic localization of the source of these lesions. Probing determines the presence of deep, isolated periodontal defects that may be endodontic in origin ( Fig. 5.5 ).

Dentition

Teeth are examined with a mirror and an explorer for discolorations, fractures, abrasions, erosions, caries, failing restorations, or other abnormalities. A discolored crown is often pathognomonic of pulpal pathosis or is the sequela of earlier root canal treatment. Although in some cases the diagnosis is very likely known at this stage of examination, a prudent diagnostician should never proceed with treatment before performing appropriate confirmatory clinical and radiographic examinations.

Clinical Tests

There are a number of special tests that can be applied to individual teeth suspected of pathologic change. These tests have inherent limitations; some cannot be used on each tooth, and the test results themselves may be inconclusive. The data they provide must be interpreted carefully and in conjunction with all the other information available. Importantly, these are not tests of teeth; they are tests of a patient’s response to a variety of applied stimuli, which can be highly variable.

Control Teeth

When using any test, it is important to include control (comparison) teeth of a similar type to the suspect tooth or teeth. Tests on these teeth educate the patient on what response to expect and provide a “calibrated” baseline for the responses to tests on suspected teeth. The patient should not be told whether the tooth being tested is a control or a suspect tooth. A patient may not respond in the same way or to the same extent when tests are repeated. The first application of the test is the most significant.

The tests used fall into two groups: percussion and palpation, which reflect the condition of the supporting tissues, and vitality tests, which provide information on the condition of the pulp.

Percussion and Palpation of Supporting Tissues

Percussion is performed by different means. One way is tapping on the incisal or occlusal surface of the tooth with the end of a mirror handle held either parallel or perpendicular to the crown. This should be preceded by gentle digital pressure to detect teeth that are very tender and should not be tapped with the mirror handle. If a painful response is obtained, this may indicate the presence of periapical inflammation. Periapical inflammation may show a sharp pain. An additional approach, useful if the patient complains of pain on chewing, is the biting test, in which the patient bites down on a cotton swab between each tooth in turn ( Fig. 5.6 ).

Both neighboring teeth and contralateral control teeth should also be percussed. Teeth adjacent to the diseased tooth often show some tenderness because of the local spread of cytokines and neuropeptides that lower the pain threshold.

At the same time the tooth is percussed, its mobility should be estimated by placing a finger lightly on the lingual surface of the tooth and pushing on the facial surface with the end of the mirror handle. The degree of movement can be visualized and felt. A healthy periodontium allows movement of only a fraction of a millimeter. Increased mobility is usually the result of periodontal disease, but in teeth with periapical inflammation, the tooth may have some mobility. This movement reduces after the periapical problem resolves.

Palpation is firm pressure on the mucosa overlying the apex. As does percussion, palpation determines how far the inflammatory process has extended periapically. A painful response to palpation indicates periapical inflammation.

Pulp Vitality Tests

Vitality tests are an important, often critical, component of the examination. Studies comparing the histologic condition of the pulp to the results of vitality tests have shown that there is only a limited correlation between the two. As a consequence, the results of these tests require very careful interpretation. There are several types of vitality tests, and each can be applied by a variety of techniques. Not all tests are appropriate for every case, nor are all tests equally reliable. There are five basic types of vitality tests. Four apply either a cold, hot, electrical, or dentin stimulus to the tooth, and the patient’s verbal response is recorded. The fifth attempts to measure pulpal blood flow, on the principle that blood flow increases in inflamed tissue and is not present with necrotic pulp. Selecting which tests to use is based on the patient’s complaint and the test’s reliability; it should be the one that reproduces the stimulus that causes the complaint.

An electric pulp test, conducted correctly, usually determines whether there is vital tissue within the tooth. It cannot determine whether that tissue is inflamed, nor can it indicate whether there is partial necrosis. The cold test can also detect vital tissue. Prolonged pain provides an indication of irreversible inflammation, although not very accurately. The heat test is the least reliable. Measuring blood flow or presence is difficult under routine conditions, but as the technology improves, this technique may become more useful.

Selecting the Appropriate Pulp Test

Selection of the appropriate pulp test depends on the situation. Additional meaningful information is collected when stimuli similar to those that the patient reports provoke pain are used during clinical tests. When cold (or hot) food or drink initiates a painful response, a cold (or hot) test is conducted in place of other vitality tests. Replication of the same symptoms in a tooth often indicates the offender. Overall, electrical stimulation is similar to cold (refrigerant) in identifying pulp necrosis ; heat is best used when this is the chief complaint.

When other tests are inconclusive or cannot be used and a necrotic pulp is suspected, dentin stimulation with a test cavity is helpful. For example, a tooth with a porcelain-fused-to-metal crown often cannot be tested accurately by standard thermal or electrical tests. After careful subjective examination and an explanation of the nature of the test to the patient, an access preparation without anesthesia is started. With a vital pulp, the surface of the restoration or the enamel can be penetrated without too much discomfort. If the pulp is vital, there will be a sudden sensation of pain when dentin is reached. In contrast, if discomfort or pain is absent, the pulp is probably necrotic; the procedure may be continued.

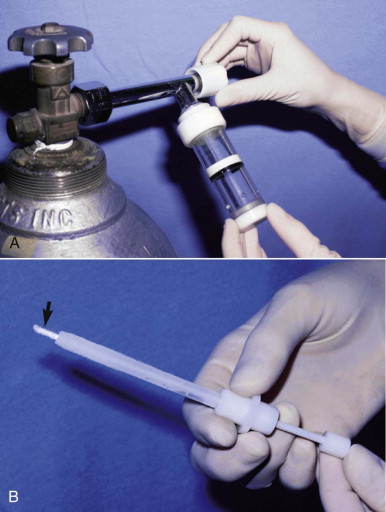

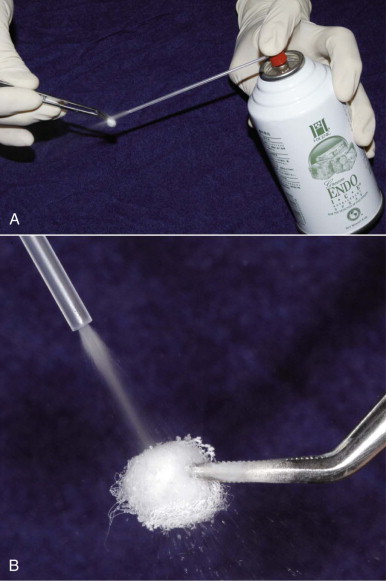

Cold Tests

Three methods are generally used for cold testing: frozen water (ice), carbon dioxide (CO 2 ) ice (dry ice), and refrigerant. CO 2 ice requires special equipment ( Fig. 5.7 ), whereas refrigerant in a spray can is more convenient ( Fig. 5.8 ). Regular ice delivers less cold and is not as effective as refrigerant or CO 2 ice. One study found that refrigerant sprayed on a large cotton pellet was the most effective in reducing temperature within the chamber under full-coverage restorations. Overall, refrigerant spray and CO 2 ice are equivalent for pulp testing.

After the tooth has been isolated with cotton rolls and dried, a CO 2 ice stick or large cotton pellet saturated with refrigerant is applied. This stimulus over a vital pulp usually results in sharp, brief pain. This short response may occur regardless of pulp status (normal or reversible or irreversible pulpitis). However, an intense and prolonged response is usually taken to indicate irreversible pulpitis. In contrast, necrotic pulps do not respond. A false-negative response is often obtained when cold is applied to teeth with calcific metamorphosis, whereas a false-positive response may result if cold contacts gingiva or is transferred to adjacent teeth with vital pulps.

Cold is more effective on anterior than posterior teeth. Lack of a response to cold on a posterior tooth indicates that another type of vitality test (electrical) should be included. Surprisingly, gingival recession and attachment loss decrease the sensitivity to cold testing.

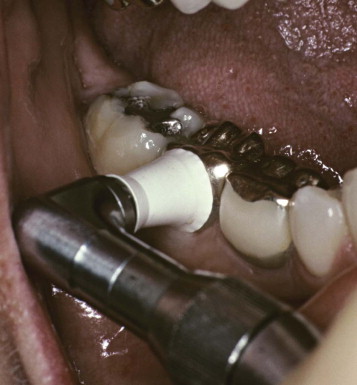

Heat Tests

Teeth are best isolated by a rubber dam to prevent false-positive responses. Various techniques and materials are used. The best, safest, and easiest technique is to rotate a dry rubber prophy cup to create frictional heat ( Fig. 5.9 ) or to apply hot water. Gutta-percha heated in a flame can be applied to the facial surface of the tooth after first coating the surface of the crown with petroleum jelly. A flame-heated instrument is difficult to control, and its use is best avoided. Battery-powered devices are better controlled and deliver heat safely and effectively.

Heat is not used routinely but is helpful when the major symptom is heat sensitivity and the patient cannot identify the offending tooth. After applying heat, the temperature is gradually increased until pain is elicited. As with cold, a sharp and nonlingering pain response indicates a vital (not necessarily normal) pulp.

Electrical Pulp Testing

All the electrical pulp testers currently available produce a high-frequency electrical current with an amperage that can be changed. These testers are also monopolar, which means that the current flows from the probe through the tooth and then through the patient back to the testing unit. Thus nerves in any part of the pulp are stimulated.

Electrical pulp testers with digital readouts are popular ( Fig. 5.10 ). These testers are not inherently superior to other electrical testers but are more user-friendly. High readings usually indicate necrosis. Low readings indicate vitality. Testing of normal control teeth establishes the approximate boundary between the two conditions. The exact number of the reading is of no significance and does not reflect subtle degrees of vitality, nor can any electrical pulp tester indicate inflammation.

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses