Management of patients with masticatory pain and dysfunction is one of the most challenging problems confronting oral and maxillofacial surgeons. The problem exists because of the diverse collection of conditions affecting the masticatory system that have similar symptoms and signs of pain or dysfunction, or both. Several diagnostic classification systems are used but are often non-specific and confusing. Selection of the appropriate treatment protocol is controversial, with treatment decisions being based on one’s philosophy of the cause of the condition. Frequently, the approach to diagnosis and treatment of a patient with masticatory pain and dysfunction is more complicated than necessary. Although the pathophysiology of masticatory pain and dysfunction is complex and poorly understood, the approach to most patients should be relatively simple.

The senior author has divided patients with masticatory pain and dysfunction into two general categories, muscular conditions and temporomandibular joint (TMJ) disorders. At the most basic level the surgeon must decide whether the pain or dysfunction, or both, are arising from masticatory muscles or the TMJ. TMJ surgery is not recommended for muscle disorders because it will not decrease the pain and dysfunction and will most likely make them worse. Only patients with pain and dysfunction arising within the TMJ are candidates for TMJ surgery.

The purpose of this chapter is to present a simple practical approach to the diagnosis and management of patients with masticatory pain and dysfunction. Emphasis will be placed on identification of patients who will benefit from surgical intervention and selection of the surgical procedure that will provide the greatest benefit for the patient’s specific problem with the least risk for complications.

Classification

Several classifications of conditions associated with masticatory pain and dysfunction have been proposed. Some are based on symptoms and signs, some on disease categories, and others on research criteria. The senior author has used a simple diagnostic classification system that should include most conditions ( Box 98-1 ).

- A

Masticatory muscle disorders

- 1

Myofascial pain and dysfunction

- a

Nocturnal bruxism

- b

Habitual daytime parafunction

- i

Clenching

- ii

Postural

- i

- c

Trauma—whiplash

- a

- 2

Myositis, myospasm, etc.

- 3

Neoplasias

- 1

- B

Temporomandibular joint disorders

- 1

Disc derangement disorders (internal derangement)

- a

Anchored disc phenomenon

- b

Disc displacement with reduction

- c

Disc displacement without reduction

- d

Disc perforation

- a

- 2

Osteoarthritis (non-inflammatory disorders)

- 3

Inflammatory disorders

- a

Capsulitis/synovitis

- b

Polyarthritides

- i

Rheumatoid arthritis

- ii

Juvenile rheumatoid arthritis

- iii

Psoriatic arthritis

- iv

Others

- i

- a

- 4

Hypermobility disorders

- a

Subluxation

- b

Dislocation

- i

Acute

- ii

Chronic recurrent

- iii

Chronic

- i

- a

- 5

Hypomobility disorders

- a

Extra-articular (pseudo)

- b

Intra-articular (true)

- i

Fibrous

- ii

Osseous

- iii

Combination of fibrous and osseous

- i

- a

- 6

Traumatic injuries

- a

Soft tissues

- b

Fractures

- i

Intracapsular

- ii

Extracapsular

- i

- a

- 7

Congenital or developmental disorders

- a

Aplasias

- b

Hypoplasias

- c

Hyperplasias

- a

- 8

Unusual diseases and disorders

- a

Benign

- b

Malignant

- i

Primary

- ii

Metastatic

- i

- a

- 1

Despite differences in opinion about which operation to perform, there are a group of disorders for which the role of surgery is not disputed, including all of the TMJ disorders except for the disc derangement and arthritic disorders. This chapter focuses on the diagnosis and management of patients with most common masticatory pain and dysfunction disorders who have either masticatory muscle or disc derangement disorders. For the purposes of this chapter, disc derangement disorders and osteoarthritis will be discussed together because they are commonly found together. However, they can certainly occur as distinct disorders.

Diagnosis

At the most basic level, the surgeon must decide whether a patient with masticatory pain and dysfunction has a muscular, joint, or combination of a muscular and joint problem. It is assumed that non-masticatory system causes of the pain have been eliminated. The diagnosis is based on a thorough history, clinical examination, and laboratory and imaging studies.

The history may be the most important part of the evaluation. It should include the chief complaint and a detailed history of the present illness. The clinical examination should be a systematic evaluation of the TMJs for tenderness, joint noise, range of motion with and without pain, and pain on loading. The muscles of mastication and the cervical muscles should be palpated and areas of tenderness noted. Finally, the teeth and occlusion should be assessed. A thorough evaluation of the soft tissues of the oral cavity should also be done. Routine imaging such as a panographic x-ray should be obtained to evaluate the osseous structures of the teeth, their supporting structures, and the TMJs. The need for more advanced imaging or laboratory studies is determined from findings on the preliminary evaluations.

Muscular Pain and Dysfunction

The concept of myofascial pain and dysfunction (MPD) was introduced by Laskin in the 1960s. It refers to a group of muscle disorders characterized by diffuse facial pain and limited mouth opening. It can involve problems with the TMJ, muscles of the face, and associated head and neck structures. Frequently, when patients have non-specific signs and symptoms of facial pain of unknown etiology, they are wrongly labeled as having a TMJ problem. In the authors’ experience, the majority of patients seen by surgeons with complaints of facial pain and dysfunction have muscular problems.

Recent advances in the understanding of muscular pain and dysfunction have supported the theory that the cause of MPD is often multifactorial. Biologic, behavioral, environmental, social, emotional, and cognitive factors contribute to the development of signs and symptoms. More specifically, there are various predisposing risk factors, such as female gender, anxiety and depression, and a stressful lifestyle. There are multiple perpetuating factors, including acute jaw trauma, sudden changes in occlusion, and excessive jaw activity. Secondary gain such as sympathy or avoidance of an unpleasant activity such as work may also perpetuate the symptoms. The significance of large skeletal discrepancies such as open-bite malocclusion, overjet greater than 6 mm, and missing posterior teeth is unclear, but such discrepancies may predispose patients to MPD.

Although many factors contribute to MPD, the single most commonly identifiable cause is a parafunctional habit such as tooth clenching or grinding, which often occurs secondary to stress and anxiety. In fact, more than 68% of patients treated for MPD report that they clench their teeth. Importantly, bruxism can overload the TMJ and contribute to the development of, perpetuate, and maintain TMJ disc derangements.

Patients with masticatory muscle pain and dysfunction have diffuse, poorly localized pain that is frequently, but not always worse in the morning. Patients generally report sleep disturbances and believe that the pain disrupts their sleep. As noted, more than 68% of patients report that they grind or clench their teeth. They may complain of sore teeth and frequently complain of jaw tiredness and fatigue when eating. They often complain of limited and painful mouth opening. Patients with MPD may also complain of headaches, earaches, and cervical pain. The findings on physical examination are diffuse tenderness to palpation of the masticatory and cervical muscles, especially along the temporalis insertion. The TMJs are either non-tender or minimally tender to palpation, and there is no pain in the TMJ on loading. Mandibular opening may be limited to 30+ mm, and patients will frequently hesitate (guard) during opening, but they can usually be encouraged to open wider. The intraoral examination helps eliminate dental causes as a source of the pain. The number and condition of the teeth, including occlusal wear facets, sore teeth, craze lines, and mobility, are documented. Such findings are an indication that patients are grinding their teeth, although absence of these signs does not eliminate bruxism. Findings on routine radiographic examination are frequently normal, but occasional abnormalities may be observed. The surgeon must remember that patients with severe TMJ signs may occasionally also have MPD as a perpetuating factor.

Because more than 80% of patients with MPD respond favorably to non-surgical interventions, all factors should be addressed with a focus on non-invasive methods that are reversible. The first step should include a thorough explanation of the findings. The patient should be educated and reassured that the pain usually resolves with simple treatment and that a more serious condition does not exist. The patient should be prescribed a home care program that includes jaw rest, a soft diet, limitation of wide mouth opening, and application of warm moist heat. After a period of jaw rest, muscle massage and physical therapy, including stretching and strengthening exercises, should be encouraged. The physical therapy program should be kept simple with exercises consisting of opening and closing the mouth, protrusion, and right and left lateral excursion of the mandible.

Most patients will benefit from an occlusal appliance, especially if they grind their teeth. The appliance should be a simple flat-plane splint that covers all the teeth, and all the teeth should touch the splint evenly in centric occlusion and in a centric relationship. The splint should have a shallow anterior guidance that separates the teeth during excursive movements. The idea is not to reposition the mandible, but to allow the muscles to rest and to decrease TMJ loading. The splint also protects the occlusal surfaces of the teeth from damage during bruxism. It should generally be worn only at night. Frequent adjustments may be necessary, especially when first given to the patient.

Medical therapy should include a non-narcotic analgesic such as a non-steroidal anti-inflammatory medication and, if sleep disturbances exist, a sleep medication such as a low-dose tricyclic antidepressant. Some tricyclic antidepressants have analgesic properties independent of their antidepressant effect and may be useful for patients who have both pain and sleep disturbances. In our experience, cyclobenzaprine has similar benefits. The combination of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and a low-dose tricyclic antidepressant appears to be most beneficial. Patients who have significant behavioral problems, stress, anxiety, or depression will benefit from psychological evaluation and treatment.

It is important to recognize that the patient’s signs and symptoms will resolve slowly over a period of weeks to months and that they will frequently recur. However, most patients with MPD will improve with conservative treatment. It is also important to encourage patients that they will improve and that severe problems rarely occur. If the patient is not improving, re-evaluation should be undertaken to determine whether the diagnosis and treatment are appropriate. TMJ surgery is not recommended for patients with MPD even if the signs and symptoms are severe and persistent. TMJ surgery will not resolve and will usually make it worse.

Relationship of Bruxism to Internal Derangement

Grinding and clenching of the teeth have been shown to adversely load the TMJ. This is especially true of clenching, which causes continued compressive loading of the TMJ tissues. Excessive loading of the joint causes damage to the joint tissues through mechanical, biochemical, and hypoxia-reperfusion mechanisms. In hypoxia-reperfusion injury, the soft tissues become temporarily hypoxic because of excessive loading of the soft tissues, and as reperfusion occurs, free radicals, which are thought to break down hyaluronic acid, are produced. This leads to a failure of the joint lubrication system and results in microscopic changes in articular cartilage, disc stickiness, disc displacement, and eventually degeneration of the articular surfaces of the TMJ.

Though not proven, there is considerable evidence to support this hypothesis. Because MPD may be a significant cause of internal derangement, they are frequently found together. The occurrence of MPD and internal derangement together results in difficulty diagnosing the patient’s condition. It is our opinion that failure to recognize this relationship, as well as failure to manage MPD before TMJ surgery for internal derangement, is the primary reason for surgical failure. When MPD is present, it must be managed appropriately if surgical success is to be achieved.

Internal Derangement

Internal derangement of the TMJ was reintroduced into the literature in the 1970s by Farrar and McCarty. During the 1970s and 1980s it gained wide popularity as the cause of TMJ pain and dysfunction. The primary clinical focus was on TMJ disc displacement and deformity as the cause of TMJ pain and dysfunction, which eventually led to TMJ osteoarthritis. The introduction of TMJ arthroscopy and the recognition that simple lysis and lavage of the upper joint space of the TMJ frequently resulted in decreased pain and improved range of motion led to re-evaluation of the significance of disc position. At the present time, internal derangement is thought to be a dynamic process involving biomechanical, biochemical, and cellular changes, including disc displacement and deformity, synovitis and changes in synovial fluid, degenerative changes in the articular surface, and fibrosis. The shift in thinking from a predominantly mechanical focus to a biologic focus has resulted in a significant change in surgical treatment from mainly open surgery to arthrocentesis and arthroscopy.

Patients with internal derangement have well-localized TMJ pain that is continuous and becomes worse with mandibular functions such as chewing and talking. They report that their TMJ either makes noise (i.e., clicking or crepitus) or previously made noise but no longer does. Patients usually complain that their jaw either does not open smoothly or is limited in its opening. Patients frequently complain of catching or locking sensations. Many patients report that their jaw is locked closed. Clearly, the focus of the patient’s complaints is well localized to the TMJ.

Physical examination demonstrates pain and dysfunction that are well localized to the TMJ. The affected TMJ is tender to palpation, and TMJ pain is reported when the joint is loaded. There is interference with smooth joint movement in the form of deviation associated with TMJ clicking or limited opening with pain. Excursive movements are limited toward the unaffected side and usually cause increased pain in the affected joint.

A preliminary diagnosis of internal derangement can generally be made from the clinical examination. Definitive diagnosis and clinical staging of the disc derangement require magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). Based on the clinical findings and MRI, the disc derangement should be classified according to the Wilkes classification system. Classification of the internal derangement is especially important for reporting outcomes of clinical treatment.

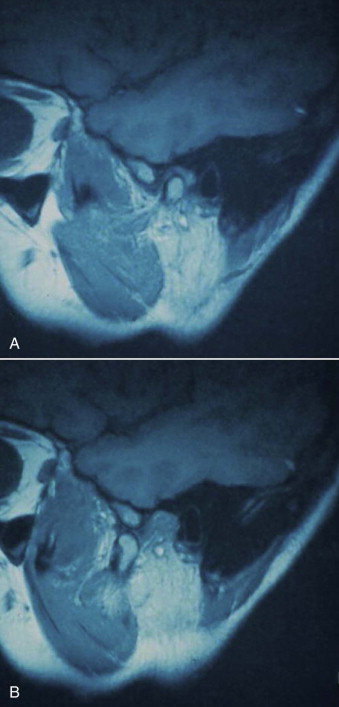

MRI of the TMJ is necessary to evaluate the position and shape of the articular disc and to confirm the diagnosis of internal derangement before open TMJ surgery ( Fig. 98-1 ). The absolute indications for MRI are not specific, other than before open TMJ surgery when the diagnosis has not been confirmed by other imaging. MRI does provide valuable information about disc shape that cannot be obtained by other means. MRI also provides information about the presence of joint effusion, marrow edema, and the integrity of the articular surfaces. It is the imaging technique of choice for evaluating the soft tissues of the TMJ. The correlation of TMJ pain with MRI findings is poor, so the diagnosis must always be made from a comparison of the clinical history, physical examination, and findings on MRI. The diagnosis should never be based solely on MRI.

Most patients with pain and dysfunction caused by internal derangement will experience resolution of their symptoms with non-surgical treatment. In fact, in many patients the symptoms resolve without treatment. Therefore, it is prudent to treat patients with non-surgical therapies before surgical options are considered.

Non-surgical treatment of TMJ internal derangement is similar to that for MPD. The objectives of treatment are to reduce pain, eliminate inflammation from the joint, eliminate or reduce adverse TMJ loading, and restore TMJ mobility.

The first step in treatment is to educate the patient about internal derangement of the TMJ. The patient should be reassured that the pain and dysfunction usually resolves with simple treatment and that a more serious condition rarely develops. The patient should be provided with a home care program that includes jaw rest, a soft diet, and limitation of jaw opening. Medical therapy should include a non-steroidal anti-inflammatory analgesic. As the pain begins to resolve, simple range-of-motion exercises should be started. These exercises include gentle unforced mandibular opening and excursive movements.

Since bruxism may be an important cause of internal derangement, many patients will require the treatment protocol for MPD; specifically, an occlusal appliance and sleep medications should be provided. The occlusal appliance should be a flat-plane appliance and not a jaw-repositioning device. The objective of treatment with an appliance is to rest the muscles of mastication and reduce adverse loading of the TMJ.

Most patients will have a decrease in symptoms in about 4 to 6 weeks. Patients who continue to have significant TMJ pain and dysfunction should be re-evaluated for surgical treatment.

Diagnosis

At the most basic level, the surgeon must decide whether a patient with masticatory pain and dysfunction has a muscular, joint, or combination of a muscular and joint problem. It is assumed that non-masticatory system causes of the pain have been eliminated. The diagnosis is based on a thorough history, clinical examination, and laboratory and imaging studies.

The history may be the most important part of the evaluation. It should include the chief complaint and a detailed history of the present illness. The clinical examination should be a systematic evaluation of the TMJs for tenderness, joint noise, range of motion with and without pain, and pain on loading. The muscles of mastication and the cervical muscles should be palpated and areas of tenderness noted. Finally, the teeth and occlusion should be assessed. A thorough evaluation of the soft tissues of the oral cavity should also be done. Routine imaging such as a panographic x-ray should be obtained to evaluate the osseous structures of the teeth, their supporting structures, and the TMJs. The need for more advanced imaging or laboratory studies is determined from findings on the preliminary evaluations.

Muscular Pain and Dysfunction

The concept of myofascial pain and dysfunction (MPD) was introduced by Laskin in the 1960s. It refers to a group of muscle disorders characterized by diffuse facial pain and limited mouth opening. It can involve problems with the TMJ, muscles of the face, and associated head and neck structures. Frequently, when patients have non-specific signs and symptoms of facial pain of unknown etiology, they are wrongly labeled as having a TMJ problem. In the authors’ experience, the majority of patients seen by surgeons with complaints of facial pain and dysfunction have muscular problems.

Recent advances in the understanding of muscular pain and dysfunction have supported the theory that the cause of MPD is often multifactorial. Biologic, behavioral, environmental, social, emotional, and cognitive factors contribute to the development of signs and symptoms. More specifically, there are various predisposing risk factors, such as female gender, anxiety and depression, and a stressful lifestyle. There are multiple perpetuating factors, including acute jaw trauma, sudden changes in occlusion, and excessive jaw activity. Secondary gain such as sympathy or avoidance of an unpleasant activity such as work may also perpetuate the symptoms. The significance of large skeletal discrepancies such as open-bite malocclusion, overjet greater than 6 mm, and missing posterior teeth is unclear, but such discrepancies may predispose patients to MPD.

Although many factors contribute to MPD, the single most commonly identifiable cause is a parafunctional habit such as tooth clenching or grinding, which often occurs secondary to stress and anxiety. In fact, more than 68% of patients treated for MPD report that they clench their teeth. Importantly, bruxism can overload the TMJ and contribute to the development of, perpetuate, and maintain TMJ disc derangements.

Patients with masticatory muscle pain and dysfunction have diffuse, poorly localized pain that is frequently, but not always worse in the morning. Patients generally report sleep disturbances and believe that the pain disrupts their sleep. As noted, more than 68% of patients report that they grind or clench their teeth. They may complain of sore teeth and frequently complain of jaw tiredness and fatigue when eating. They often complain of limited and painful mouth opening. Patients with MPD may also complain of headaches, earaches, and cervical pain. The findings on physical examination are diffuse tenderness to palpation of the masticatory and cervical muscles, especially along the temporalis insertion. The TMJs are either non-tender or minimally tender to palpation, and there is no pain in the TMJ on loading. Mandibular opening may be limited to 30+ mm, and patients will frequently hesitate (guard) during opening, but they can usually be encouraged to open wider. The intraoral examination helps eliminate dental causes as a source of the pain. The number and condition of the teeth, including occlusal wear facets, sore teeth, craze lines, and mobility, are documented. Such findings are an indication that patients are grinding their teeth, although absence of these signs does not eliminate bruxism. Findings on routine radiographic examination are frequently normal, but occasional abnormalities may be observed. The surgeon must remember that patients with severe TMJ signs may occasionally also have MPD as a perpetuating factor.

Because more than 80% of patients with MPD respond favorably to non-surgical interventions, all factors should be addressed with a focus on non-invasive methods that are reversible. The first step should include a thorough explanation of the findings. The patient should be educated and reassured that the pain usually resolves with simple treatment and that a more serious condition does not exist. The patient should be prescribed a home care program that includes jaw rest, a soft diet, limitation of wide mouth opening, and application of warm moist heat. After a period of jaw rest, muscle massage and physical therapy, including stretching and strengthening exercises, should be encouraged. The physical therapy program should be kept simple with exercises consisting of opening and closing the mouth, protrusion, and right and left lateral excursion of the mandible.

Most patients will benefit from an occlusal appliance, especially if they grind their teeth. The appliance should be a simple flat-plane splint that covers all the teeth, and all the teeth should touch the splint evenly in centric occlusion and in a centric relationship. The splint should have a shallow anterior guidance that separates the teeth during excursive movements. The idea is not to reposition the mandible, but to allow the muscles to rest and to decrease TMJ loading. The splint also protects the occlusal surfaces of the teeth from damage during bruxism. It should generally be worn only at night. Frequent adjustments may be necessary, especially when first given to the patient.

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses