Dens evaginatus is a rare dental anomaly that occurs during tooth development and results in an abnormal protrusion from the occlusal surface of the affected tooth, often in the area of the central groove between the buccal and lingual cusps. Of clinical importance to the orthodontist is that these occlusal tubercles fracture easily or can be worn away, resulting in direct pulp exposure in a noncarious tooth. This can cause severe complications, including loss of tooth vitality, facial infection in the form of an abscess or cellulitis, or osteomyelitis of the jaw. If extraction of premolars is indicated for orthodontic treatment after careful diagnosis and treatment planning, it is paramount to establish the health of the premolars that will remain in the dentition before extracting the teeth.

Historically, a common and difficult challenge to orthodontists is the appropriate management of an arch-length discrepancy. How to responsibly and most effectively resolve the crowded arch, considering smile esthetics, occlusion, periodontal health, facial balance, and long-term stability, can be a daunting task and maintains an element of controversy in our specialty. The parameters mentioned above, some of which are quite subjective, understandably receive most of our attention when developing a treatment plan for the crowded arch. Less often does the health of the teeth considered for possible extraction come into play during this diagnostic process, especially in the treatment of an adolescent patient. The purpose of this article is to highlight a particular dental anomaly that, although rare, should always be considered in the diagnosis and treatment planning for a crowded arch. Moreover, if undiagnosed, this anomaly could have unfavorable consequences to the orthodontic outcome.

Dens evaginatus (DE) is a rare dental anomaly that occurs during tooth development. During the bell stage of tooth formation, an extra cusp or tubercle is formed by abnormal proliferation of the inner enamel epithelium into the stellate reticulum of the enamel organ with a core of dentin surrounding a narrow extension of pulp tissue. This results in an abnormal protrusion from the occlusal surface of the affected tooth, often in the area of the central groove between the buccal and lingual cusps. Although it can occur on any tooth in the maxilla or the mandible, DE most commonly affects the mandibular premolars. DE is 5 times more frequently observed in the mandible than in the maxilla. This anomaly occurs more often in female patients and can occur unilaterally or bilaterally, and the occlusal tubercle is often large enough to cause occlusal interferences. These tubercles most often appear on the occlusal surfaces of posterior teeth and the lingual surfaces of anterior teeth. In 1892, DE was first documented in the literature, although its etiology was not identified. Its prevalence is between 1% and 4%, most commonly in people of Asian descent, including Filipinos, Indians of North America, Eskimos, Chinese, Thais, and Japanese. In specific Alaskan Eskimo natives, prevalence as high as 15% has been observed.

Of clinical importance is that these occlusal tubercles fracture easily or can be worn away by occlusal forces, resulting in direct pulp exposure in a noncarious tooth. These tubercles can extend up to 3.5 mm from the occlusal surface in posterior teeth and up to 6.0 mm from the lingual surface in anterior teeth. This can cause severe complications, including loss of tooth vitality, facial infection in the form of an abscess or cellulitis, or osteomyelitis of the jaw.

Case report

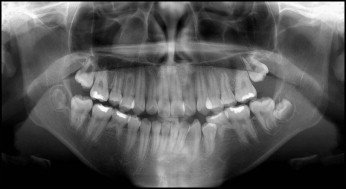

A 13-year-old Asian girl came to a private pediatric dental practice on a Thursday for an oral evaluation with a chief complaint of sensitivity in the left posterior maxilla. The patient had a history of occlusal caries of the maxillary left first molar, which had been restored with resin composite 5 months previously. On clinical evaluation, the patient isolated discomfort in the partially erupted mandibular second molars. However, her primary concern remained the sensitivity in her maxillary left quadrant. Although she did not describe it as a throbbing pain, she reported pain during the night that was not relieved with nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. The results for percussion, palpation, and mobility of all teeth were negative. A panoramic radiograph was taken and fluoride varnish applied to all teeth. The initial evaluation of the panoramic radiograph was unremarkable, with no obvious cause of pain observed ( Fig 1 ). The patient was missing her mandibular second premolars but had retained the mandibular second deciduous molars and had mild to moderate crowding in both arches.

During a follow-up phone call the next morning, Friday, the patient had the same chief complaint of pain in the left posterior maxilla that was unresolved with nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. An office staff member instructed the patient to use Sensodyne toothpaste (GlaxoSmithKline, London, United Kingdom) and observe. At 5:15 pm , a translator called the office to report that the patient was still experiencing nonlocalized pain in the left posterior maxilla, but there was no swelling. She was instructed to continue with the nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, observe, and call if any changes occurred.

The following day, Saturday, the translator called the clinic in the afternoon to report that the patient had swelling on the left side of her face. The pediatric dentist on call prescribed an antibiotic, instructed them to observe the patient for the rest of the day and call on Sunday if the swelling did not resolve. On Sunday morning, the translator called and reported that the swelling had worsened overnight and now involved the patient’s left eye. She was referred to the emergency room for intravenous antibiotics, and the on-call pediatric dentist phoned the hospital with the reason for the referral and asked emergency room personnel to call after the assessment. The patient chose to be treated by a family friend for the intravenous antibiotics, and she was appointed to return to the dental office on Monday at 7:45 am .

After her examination on Monday, the patient was referred to an endodontist for evaluation of the maxillary left first premolar and possible root canal therapy. The treatment rendered included pulpal debridement, followed by incision and drainage. The endodontist attributed the pulpal inflammation to excessive prophy-cup heating during the patient’s prophylaxis the previous month by the referring pediatric dentist during a preventive care visit. Before completing the endodontic therapy, the patient was referred for an orthodontic evaluation. The orthodontist (L.S.L.), who was also trained in pediatric dentistry, recognized the abnormal tubercle pattern and the internal resorption of the maxillary right first premolar and subsequently recommended extraction of both maxillary first premolars, as well as the retained mandibular second deciduous molars ( Figs 2-4 ). As a precaution, resin was place on the occlusal surfaces of the remaining premolars, and the lingual aspects of the maxillary incisors were sealed. Brackets were not placed on the maxillary second premolars until the roots had been allowed to completely develop and their developmental and pulpal status could be properly assessed ( Fig 5 ).