Figure 3.17 Anatomical drawing depicting pain locations (shaded areas): (a) face/jaw pain; (b) dentoalveolar pain.

G. Intraoral Status

- Tooth 16 missing.

- No caries, no periodontal disease, good oral hygiene.

- Soft tissues appear normal in the pain region, no swelling or redness.

- Dentoalveolar pain is localized to alveolar ridge and buccal area regio 16 (Figure 3.17b).

- Slight percussion tenderness upper molars bilaterally.

- Pulp vitality of teeth 15, 17, and 18 confirmed by electric pulp test.

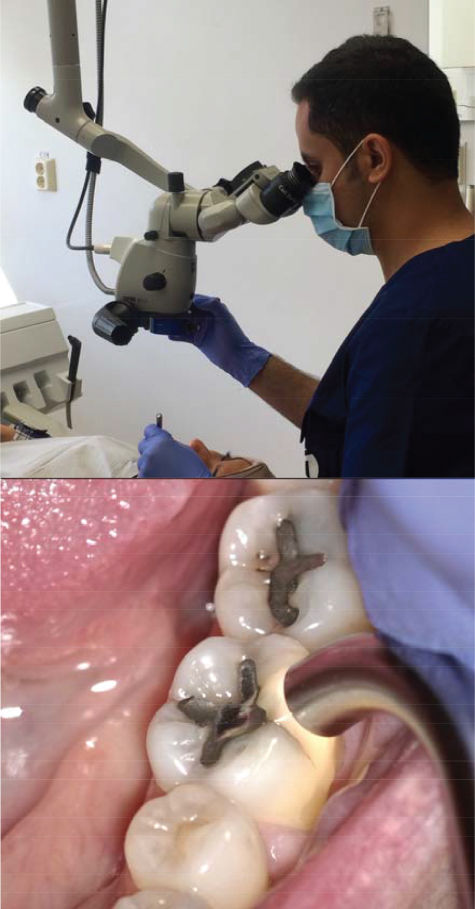

- Microscope inspection with transillumination shows no tooth pathology (Figure 3.18).

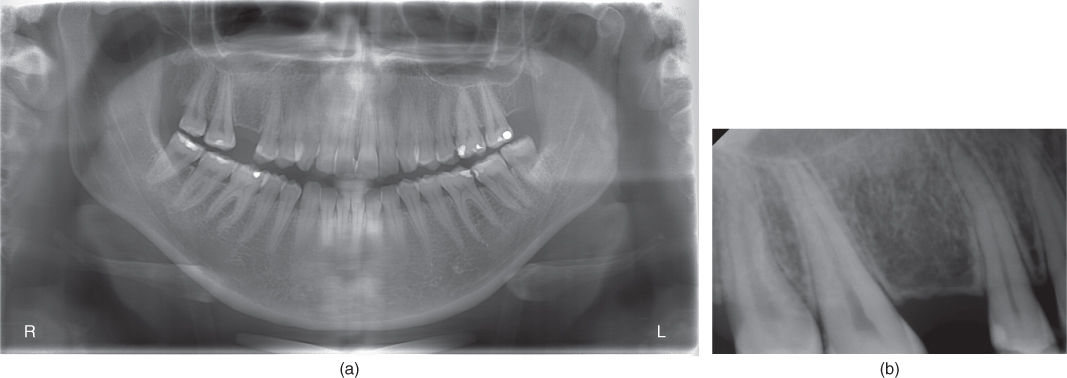

- Radiographic examination shows no hard tissue pathology in the pain region (Figure 3.19).

- Occlusal contacts only on posterior teeth in intercuspal position.

- Dental wear according to age.

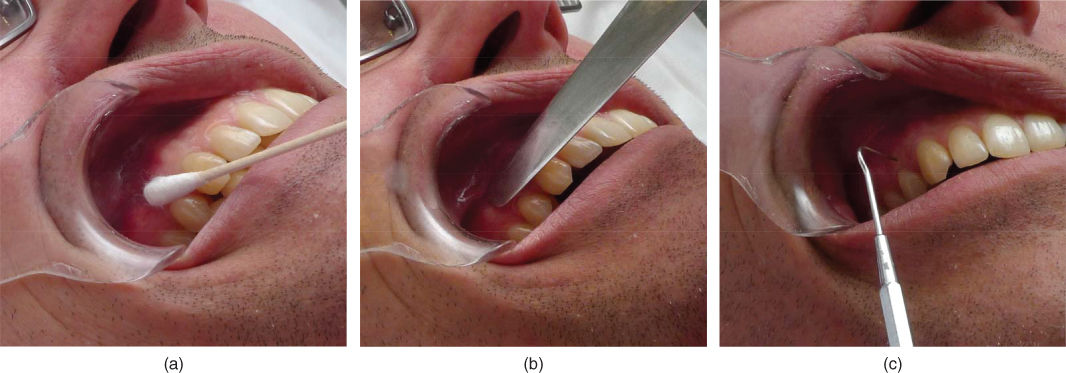

- Intraoral (region 16 with region 26 as control) qualitative sensory examination (QualST; see Figure 3.20 and Fundamental Points box) shows side differences: hypoesthesia to touch, hypoesthesia to cold, and hyperalgesia to pinprick, and repetitive pinprick stimulation increases pain from 4 to 7 (NRS 0–10); that is, sensory disturbances in the painful dentoalveolar region.

Figure 3.18 Operating microscope and enhanced light facilitates careful examination of teeth in the pain region.

Figure 3.19 Pain is located to the right upper jaw, where tooth 16 was extracted after pain onset. Panoramic (a) and periapical (b) radiographs without signs of pathology.

Figure 3.20 Example of intraoral qualitative sensory examination (QualST). Simple, easily available tools are used to compare the patient’s perception of (a) touch, (b) cold, and (c) pinprick pain between pain site and corresponding contralateral gingival site.

H. Additional Examinations and Findings

- Intraoral quantitative sensory testing (QST; see Fundamental Points box): confirmed sensory abnormalities in the pain region:

- hypoesthesia to light mechanical stimulus (touch);

- hyperalgesia to cold and to heat;

- mechanical pain (pinprick) threshold within the normal interval but considerably lower on the pain side.

- Diagnostic anesthesia: 40% pain reduction after infiltration injection with ropivacain; from initial 7 to 4 after 15 min and after 1 h and 5–6 after 6 h (NRS 0–10).

I. Diagnosis/Diagnoses

Other

- Atypical odontalgia (AO)/persistent dentoalveolar pain (PDAP) region 16.

- Myalgia neck muscles.

ICHD-3 beta

- Persistent idiopathic facial pain.

DC/TMD

- Myalgia of masticatory muscles.

- Disc displacement with reduction right TMJ.

J. Case Assessment

- The dentoalveolar pain is suspected to be of neuropathic origin, although according to the patient’s recollection no causative traumatic event in close timewise relationship with the pain could be clearly identified in the history. Central and/or peripheral mechanisms may be perpetuating the pain.

- Demonstration of sensory disturbances in the painful dentoalveolar region and V:2 extraorally.

- The sensory disturbances respect relevant neuroanatomical boundaries.

- Myalgia may be secondary to central sensitization.

- Disc displacement not bothersome to the patient

- Some degree of psychosocial distress.

- If bruxism is present, it may possibly contribute to myalgia and jaw fatigue, since this pain was reduced by occlusal appliance. Dentoalveolar pain, however, was not affected and therefore unlikely to be related to bruxism.

K. Evidence-based Treatment Plan including Aims

- Information about likely origin and causes of pain. Aim: educate the patient about the condition and reduce fear of malignant causes.

- Topical anesthesia (10% lidocaine cream deposited in soft splint with reservoir region 16; Figure 3.21). Aim: reduce peripheral sensory input from dentoalveolar pain area.

- Pharmacological treatment: pregabalin starting at 25 mg/day. Aim: reduce dentoalveolar pain and central sensitization.

- Psychological management based on CBT or acceptance and commitment therapy (ACT) principles. Aim: reduce affective/cognitive perpetuating factors.

- Jaw relaxation and exercises. Aim: reduce tension, fatigue, and pain in masticatory muscles.

Figure 3.21 Soft splint with a reservoir in the pain region for deposition of lidocaine cream (in this example, a reservoir in region 43 is shown).

L. Prognosis and Discussion

- After 3 months on pregabalin (daily dose stabilized to 2–3 × 50 mg) the pain was reduced to 1 in the mornings, increasing over the day to 4–5 (NRS 0–10).

- Patient also used soft splint with lidocaine cream regularly according to need, with good but temporary effect.

- Patient completed a CBT/ACT-based “pain school” program and learned strategies to function well despite ongoing pain.

- AO/PDAP is a chronic, often treatment-resistant, condition with no known cure.

- Treatment aims to reduce pain to a tolerable level.

- Multimodal management is an often recommended strategy (see Fundamental Points box), which was successful in this case.

- Prognosis is uncertain as to complete pain resolution.

Background information

- AO/PDAP has been estimated to occur in 1.4–5.5% of patients after endodontic treatment (Nixdorf et al., 2010).

- AO/PDAP is often described as continuous and localized pain in one or more teeth or in the extraction region after tooth removal, in the absence of any dental cause (Woda et al., 2005; Baad-Hansen, 2008). The pain is also usually described as continuous or present during most of the day, and non-paroxysmal in character.

- AO/PDAP may be considered a diagnosis of exclusion, which is unsatisfactory from a research perspective. The diagnosis has long been considered part of the group of idiopathic orofacial pain conditions (Woda et al., 2005), but in recent decades there is increasing evidence supporting a neuropathic origin, including sensory disturbances and abnormal trigeminal reflexes (Forssell et al., 2015). Hence, AO/PDAP may (at least in some cases) be of neuropathic origin due to damage to trigeminal afferent nerve fibers in association with, for example, endodontics, dentoalveolar surgery, or injection trauma/local anesthetic neurotoxicity.

- In cases where there is no clear evidence of nerve damage, AO/PDAP may be best grouped as “functional” pain (in terms of pathophysiological mechanism), with generalized hyperexcitability of the somatosensory system despite the absence of any demonstrable disease or nerve damage (Woolf et al., 1998; Forssell et al., 2015).

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses