Figure 2.2 A 34-year-old Swedish man with bilateral TMJ arthritis and referred to orofacial pain specialist from general practitioner due to TMJ pain and chewing difficulties.

B. Symptom History

- Today the pain is from the right TMJ at rest, movement, and chewing. When the pain intensity increases, a spread of the pain area occurs with pain in the ear, eye, upper molars, and temple, all on the right side. Difficulties opening mouth wide as before.

- Chewing, mouth opening, and talking worsens the pain. Rest and ibuprofen may decrease the pain. Otherwise, no apparent fluctuation of pain intensity during the day or night.

- Pain intensity varies between 3 at rest and 8 on mouth opening (NRS 0–10).

- Characteristic pain intensity 40 (NRS 0–100), current pain intensity 3 (0–10 NRS), pain-related disability 62 (NRS 0–100; GCPS).

- JFLS reveals limitation in mouth opening and chewing. Few and infrequent daytime parafunctions according to OBCL.

- No headache. No neck pain.

- Grating sounds from both TMJs.

- Debut (pain) 9 months ago after falling at a party. Trauma to the left side of the face but with only very minor soft tissue injury. The next day severe pain and difficulties opening the mouth. Pain and movement difficulties subsided, but not fully, during the first 3 weeks (self-medication with paracetamol and ibuprofen). Since 1 month later, increasing pain and opening difficulties.

- Six months ago the patient noticed difficulties chewing food due to occlusal changes. Since then a gradual loss of occlusal contacts, especially in the front. Today, no contacts in the front and harder contacts on the right side (molar and premolar area) resulting in gradually increasing chewing difficulties.

C. Medical History

- Healthy, no medications.

D. Psychosocial History

- Married, one child (4 years of age).

- Works in a truck garage shop, enjoys his work very much. Few sick-leave days in general, two last months sick-leave for about 10 days in total due to the orofacial pain.

- In his spare time: gym, family, friends, and parachuting.

- Describes himself as a stable person normally but with limited stress management. Moderate scores for depression (PHQ-9) and anxiety (GAD-7). Some physical symptoms (PHQ-15; 11 p) but high level of stress (PSS-10). Poor sleep quality (PSQI).

- GCPS grade III; that is, high and moderately limiting disability.

- No smoking, moderate alcohol consumption.

E. Previous Consultations and Treatments

- General practitioner who suspected arthralgia and myalgia of the masticatory system. The dentist made an attempt to treat the arthralgia with a stabilization splint for 4 months with no effect on the TMJ pain.

- Increasing occlusal changes, also on the splint, during the treatment period prompted the referral.

F. Extraoral Status

Asymmetries

- No apparent swelling or other facial asymmetries. No redness. No increased skin temperature over either TMJ.

Somatosensory abnormalities

- Mandibular branch on right side shows hyperesthesia for touch and cold and hyperalgesia to pinprick compared with the contralateral side.

- Normal findings for the other two branches of the trigeminal nerve on the left side (compared with the right side) regarding touch, cold, and pinprick.

TMJ

- No familiar palpation pain on either side. Reduced translatory movement on the right side. Pain from the right TMJ on mouth opening, laterotrusion to the left, and on protrusion.

- Palpable crepitus from both TMJs.

Masticatory muscles

- Familiar palpation pain in right and left masseter muscles and in the temporal muscle insertion on the right side. No referred pain.

Jaw movement capacity

- Maximum mouth opening without pain is 22 mm, maximum unassisted opening is 30 mm with familiar pain in right TMJ, and maximum assisted mouth opening is 42 mm with familiar pain in the right TMJ. Right laterotrusion 10 mm (no familiar pain), left laterotrusion 5 mm with familiar pain in the right TMJ and masseter muscle, and protrusion 6 mm with familiar pain in the right TMJ.

Neck examination

- Normal range of motion; no familiar neck pain on movement or palpation.

G. Intraoral Status

Soft tissues

- Normal findings.

Hard tissues and dentition

- Complete dentition with few and minor fillings.

Occlusion

- Dentition: 17–24, 26, 27, 37–45, 47. Hard occlusion shows contacts on the following teeth in the upper jaw: 17, 24, 27 (Figures 2.3 2.4, and 2.5).

Figure 2.3 Frontal view of occlusion on hard biting. Loss of anterior contacts.

Figure 2.4 Right side view of occlusion on hard biting. Loss of anterior contacts, only contact between 17 and 47.

Figure 2.5 Left side view of occlusion on hard biting. Loss of anterior contacts, only contact between 24–34 and 27–37.

H. Additional Examinations and Findings

- The occlusal changes motivate a radiographic examination, especially regarding the left TMJ. The purpose would be to identify structural changes due to an inflammatory process in both TMJs that may explain the anterior open bite and help deciding if treatment would be required of none, one or both TMJs.

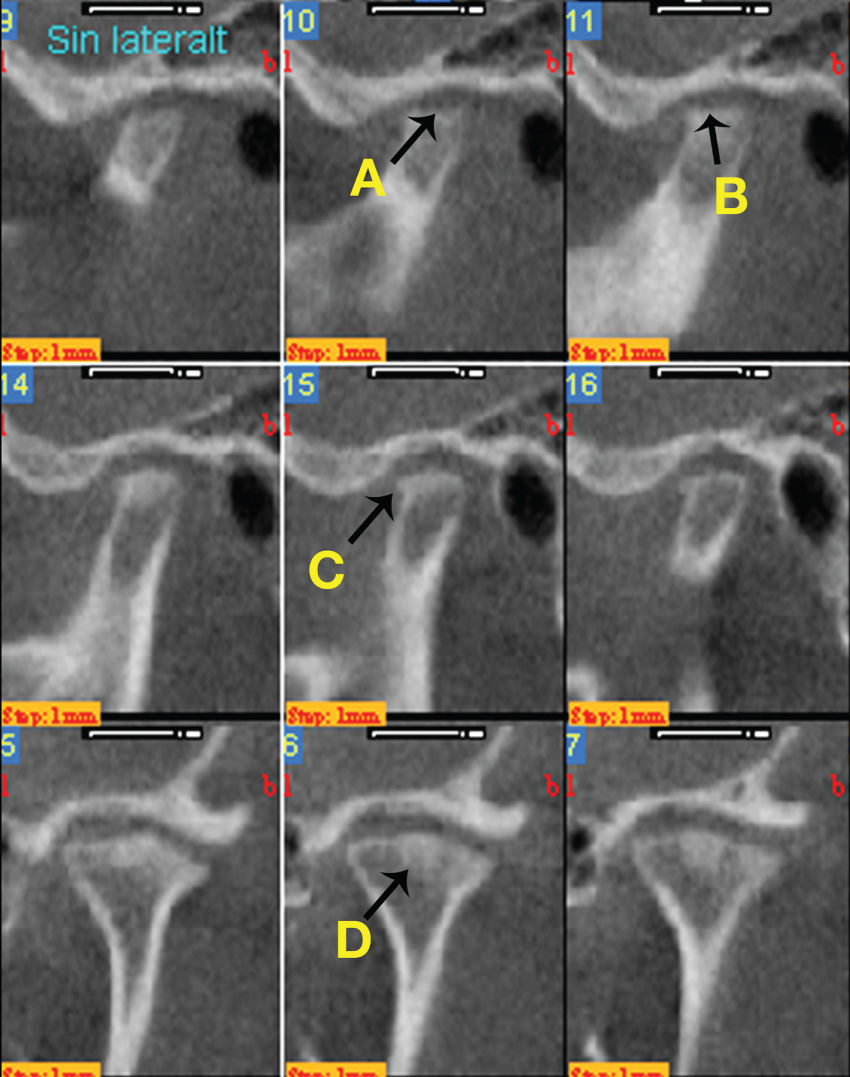

- The radiographic examination was performed by a radiologist using a bilateral cone-beam computerized tomography (CBCT) of both TMJs. This examination showed substantial structural changes in both TMJs with signs of condylar erosions and loss of compact bone on both condyles, bilateral condyle bone loss, condylar and temporal flattening as well as bilateral osteophytes (Figure 2.6).

Figure 2.6 CBCT of both TMJs showing substantial structural changes in both TMJs with signs of condylar erosions and loss of compact bone on both condyles and bilateral condyle bone loss (A), condylar and temporal flattening (B), bilateral osteophytes (C), and sclerosis (D).

I. Diagnosis/Diagnoses

Expanded DC/TMD taxonomy

- Right TMJ arthritis.

DC/TMD

- Arthralgia in the right TMJ.

- Bilateral TMJ degenerative joint disease.

- Myalgia of the masticatory muscles.

Other

- Left TMJ arthritis.

J. Case Assessment

- Many factors point to a bilateral TMJ arthritis as the main problem: continuous and sometimes intense pain on mouth opening and chewing in the right TMJ as well as pain on all mandibular movements (opening, laterotrusion. and protrusion) in the right TMJ. In addition, bilateral TMJ crepitus, bilateral radiographic signs of structural changes in accordance with inflammation and with signs of probable ongoing inflammatory activity (erosions, loss of compact bone). The anamnesis points to a trauma that very well may have induced a traumatic arthritis that now has become chronic with both pain and structural changes, resulting in occlusal changes, as a consequence.

- The patient also had myalgia and degenerative joint disease in the right TMJ. The myalgia is probably to a substantial part a consequence of a local sensitization since there are no other indications of a muscle tension problem.

- The diagnosis degenerative joint disease in DC/TMD is based on the presence of crepitus. The crepitus in this particular patient is most likely a consequence of inflammatory damage to articular cartilage and bone tissue (i.e., part of the arthritis).

- There were somatosensory abnormalities in the right trigeminal branch III that have to be interpreted as consequences of the TMJ arthritis on the same side that comprised pain. No neuropathic-type pain can be suspected.

K. Evidence-based Treatment Plan including Aims

- The main problem seems to be a traumatic bilateral TMJ arthritis that has become chronic. The initial treatment should therefore be anti-inflammatory with the goal to stop the inflammatory activity in both TMJs. It is, however, very important to supplement the pharmacological anti-inflammatory treatment with a treatment modality that has the possibility to reduce the risk of a relapse of the arthritis. For example, jaw exercise.

- When the inflammatory activity is substantially reduced and under control, the reduced chewing ability, probably in part due to the occlusal changes, should be addressed. The aim for this part should be adequate chewing ability and stable, comfortable occlusion.

- Initial treatment: anti-inflammatory treatment of both TMJs. Treatment options range from intraarticular corticosteroids, NSAIDs per os, de-loading of the joint (splint) and jaw exercise (Kopp and Wennerberg, 1981; Nicolakis et al., 2002; Ta and Dionne, 2004; Conti et al., 2006; Fredriksson et al., 2006).

- When the inflammatory activity in both TMJs is under control, the reduced chewing ability due to the occlusal changes should be addressed. Treatment options range from no treatment and natural normalization of the occlusion, via occlusal adjustment, prosthodontic therapy, orthodontic therapy, surgery, or combinations of these. The goal here must be increased or normalized chewing capacity. Also, the treatment should be minimal, since there is an increased risk of future arthritic episodes that may have the possibility to further change the occlusion.

L. Prognosis and Discussion

- The prognosis is very much dependent on how well it will be possible to stop the inflammatory activity. The supposedly long duration of arthritis, including pain and later occlusal changes due to the bone tissue destruction, is a negative prognostic factor. The short-term prognosis for treatment of arthritis must be considered as good, especially if intraarticular corticosteroids are used. However, the long-term prognosis is unclear and depends on how well the inflammation will be controlled, also over time.

Background Information

- Arthritis (i.e., inflammation in articular tissues) in the TMJ is a disorder due to either local factors like micro- or macrotrauma, secondary to disc displacement or degenerative joint disease or infection or part of a systemic inflammatory disorder such as rheumatic diseases or reactive arthritis.

- Inflammation is a complex, rapid, first-line and highly unspecific immune system response with the purpose to locate and eliminate pathogens and injured tissue as well as to promote tissue healing. This reaction has a clear and important biologic purpose in the acute phase but may transfer into a chronic state with very unclear, if any, biologic purpose. The unspecific nature means that, regardless of cause, the reaction to a great extent involves the same cells, mediators, enzymes, and so on. In addition, autoantibodies and autoinflammation may contribute to initiate and maintain the chronic inflammation (Doria et al., 2012).

- Signs and symptoms of arthritis can lie on a continuum from no signs/symptoms to a combination of pain, swelling/exudate, tissue degradation and/or growth disturbance. The presentation at any time point may include none or one or more of these signs and symptoms. On the other hand, TMJ arthritis may cause arthralgia, but arthralgia could also be due to other factors that trigger articular nociceptors (e.g., noxious mechanical stimuli), referred pain, and general/central sensitization. However, pain is likely the most common clinical finding in TMJ arthritis (Peck et al., 2014).

- There are no established diagnostic criteria for TMJ arthritis. The Expanded DC/TMD suggests swelling, redness, increased temperature, and pain as a starting point for research into diagnosis. However, swelling, redness, and increased temperature are extremely rare findings in TMJ arthritis. Also, there can be arthritis without pain but with disease progression occurring, causing tissue degradation and/or growth disturbance. Therefore, the use of cardinal signs of inflammation as the only basis for clinical diagnosis of TMJ arthritis may lack clinical utility (Peck et al., 2014).

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses