Figure 3.22 Facial photograph of patient.

B. Symptom History

- Gradually increasing swelling right cheek last year.

- Intermittent mild, aching pain right cheek.

- Pain worsens with chewing.

- Mild tenderness right cheek.

- Characteristic pain intensity 13 (NRS 0–100), current pain intensity 0 (NRS 0–10), no pain-related disability. Pain primarily localized to right masseter muscle and TMJ, but mild pain eventually occurs also left masseter region, especially in morning. JFLS reveals no limitation in jaw function. No frequent gum chewing, but reports grinding and clenching a few nights per week (girlfriend has noticed) and daytime grinding and clenching, as well as press, touch, or hold teeth together other than while eating and to hold or jut jaw to the side frequently while studying and some other daytime parafunctions (OBCL).

C. Medical History

- Previously healthy, allergic to pollen, cats, dogs, and horses.

- Broke his left arm when cycling as a child and has had some blows to the body during floorball play, but no severe hits and no fractures.

- Frequent headache localized to forehead, temples, and back of head. Headache is sometimes present at awakening, but may also develop throughout the day. Neck and shoulder muscles often feel sore. Otherwise no pains.

D. Psychosocial History

- Single, no children, lives in an apartment in Stockholm. Satisfied with home situation.

- Studying second year at Stockholm University (mathematics); plans for a master’s degree. Very satisfied with school situation. Frequent computer work.

- Exercises regularly at a gym and plays floorball once per week.

- Describes himself as a calm person, but with high current stress level due to demanding studies. He felt a little lacking in energy, but has no depression according to PHQ-9 and no anxiety according to GAD-7 No physical symptoms according to PHQ-15. Low grade of stress according to PSS-10. Moderately good sleep quality.

- Nonsmoker, moderate alcohol consumption.

E. Previous Consultations and Treatment

- Patient noticed the swelling on the cheek and consulted a general physician.

- Referred to hospital for further examination to rule out tumor by a CT scan. No tumor was found.

F. Extraoral Status

Face

- Facial asymmetry with a single, large swelling of approximately 4 cm in diameter in anterior–posterior direction present on the right angle area of the mandible (Figure 3.22).

Temporomandibular joint

- Left-side clicking at opening and closing movement.

- No pain on palpation.

Masticatory muscles

- Right masseter feels firm and hard upon palpation.

- Familiar pain on palpation masseter and temporalis muscle right side (familiar to his headache) and left lateral pterygoid muscle. No referred pain on palpation.

- No pain on palpation of other jaw muscles.

Jaw movement capacity

- Maximum unassisted jaw opening 55 mm; maximum assisted jaw opening 57 mm. No pain.

- Laterotrusion to the right 10 mm, left 11 mm; protrusion 8 mm. No pain.

Neck

- Normal movement capacity neck; no movement-evoked pain.

- No pain to palpation neck muscles (trapezius, sternocleidomastoideus).

G. Intraoral status

Soft tissues

- Bilateral mucosal ridging buccal mucosa. No tongue scalloping. Normal salivary flow.

Hard tissues

- Full dentition except mandibular third molars. Few restorations (occlusal composite fillings first mandibular molars). Slight attrition canines, more evident wear right side where active bruxism facets were noted. Vertical overbite 2 mm; horizontal overjet 2 mm. Normal sagittal relations.

Occlusion

- Bilateral contacts premolars and molars in intercuspal position. Canine and anterior guidance. Mediotrusive contact tooth 27, no laterotrusive or protrusive interferences.

H. Additional Examinations and Findings

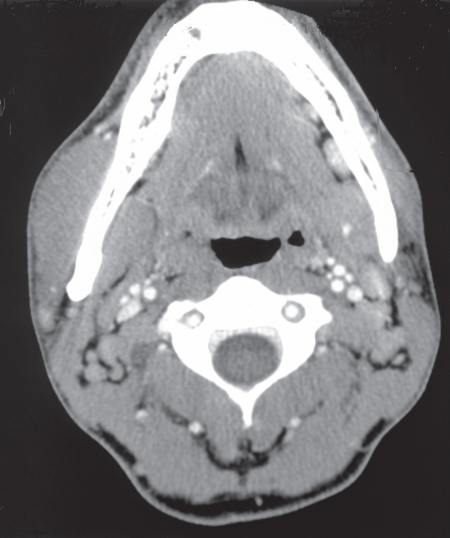

- CT scan revealed an enlarged masseter muscle right side, but with otherwise normal appearance (Figure 3.23).

Figure 3.23 CT showing right side masseter (and pterygoid muscle) hypertrophy.

I. Diagnosis/Diagnoses

Expanded DC/TMD

- Hypertrophy right masseter muscle.

DC/TMD

- Myalgia.

- Headache attributed to TMD.

- Disc displacement with reduction left TMJ.

J. Case Assessment

- From the OBCL it was apparent that the patient was aware of frequent day- and nighttime parafunctions, and when questioned in detail about it he recalled that he frequently was grinding the canines on the right side when studying (Figure 3.24). This had started as a bad habit, but now he did not think so much about it. He had noted that his jaw muscle pain and headache worsened when he was more stressed, such as before exams.

- The signs of attrition and bruxism facets on the right canines supported that the hypertrophy was due to unilateral tooth grinding.

- Medically the patient was healthy. Neck–shoulder pain and headache deemed to be work- and stress-related. Because of the demanding studies he felt stressed but said that the stress was under control.

- There were no signs of dental infections and no suspicion of parotitis or myositis. To rule out the suspicion of tumor he was referred for a CT examination.

Figure 3.24 Patient showing how he grinds his teeth at the right side. The hypertrophic masseter is clearly visible.

K. Evidence-based Treatment Plan including Aims

Treatment goals

- To reduce muscle hyperactivity and relieve pain.

Management

- The patient was informed about the nonmalignant condition and the cause of the muscle enlargement. He was also informed about the relation between psychosocial stress and bruxism and of “work hygiene” during computer work and studies and instructed in relaxation techniques. To avoid daytime grinding he was recommended visual feedback, and an occlusal appliance was made to reduce nighttime muscle activity. He was followed for 3 months, during which time the jaw muscle pain and morning headache totally disappeared. He still eventually had headache in the daytime, but much less frequent. The muscle hypertrophy was still there but did not bother him.

L. Prognosis and Discussion

- As masticatory muscle hypertrophy is a benign condition the prognosis is good and treatment is often not needed. Case studies have shown reduction in muscle size with time. In this case the patient was satisfied with the information he received that the swelling would probably normalize with time. The most important factor for normalization of muscle size was to discontinue the daytime parafunction with grinding of the right canines. This may be difficult as the patient is usually unaware of the parafunction. Visual feedback is a type of biofeedback that instead of technical devices relies on the eye, such as by posting colored stickers at different places/devices that the individual sees/uses every day (e.g., the cell phone) to remind the individual about the parafunction. Because of his intermittent pain from jaw muscles and the suspicion of nocturnal bruxism the patient also received a stabilization appliance to reduce masticatory muscle load. As he experienced a stressful life situation he was informed about its relation to bruxism and instructed in relaxation techniques and to take pauses during computer work.

- It is important also to rule out parotitis and tumors as etiologic factors. These often show similar symptoms; that is, a firm, non-fluctuant swelling of the cheek and are usually relatively painless (Table 3.1).

Table 3.1 Differential diagnoses to unilateral masticatory muscle hypertrophy

|

Source: adapted after Katsetos et al. (2014).

Background Information

- Enlargement of masticatory muscles is considered a relatively rare finding, and the literature mostly consists of case presentations. It is often not associated with pain, although occasionally some individuals may complain of pain. Masticatory muscle hypertrophy occurs most frequently in Pacific Asians, is associated with ethnic characteristics and dietary habits, is more common in younger individuals, and is slightly more prevalent in men (Sannomya et al., 2006; Fedorowicz et al., 2013).

- The hypertrophy is mostly bilateral, and unilateral cases seem rarer. Most cases presented involve the masseter muscle, but it may also affect the temporalis and pterygoid muscles, or combinations of them (Albuquerque et al., 2012; Katsetos et al., 2014).

- Masticatory muscle hypertrophy is divided into acquired and congenital forms. The etiology is controversial and includes muscle hyperfunction (bruxism, gum or betel chewing) and/or chronic tension of the muscles, unilateral chewing (unilateral cases), imbalance in the extrapyramidal neurotransmitters, HIV infection, use of anabolic steroids, mandibular retrognathia, and genetic factors (Albuquerque et al., 2012; Katsetos et al., 2014; Peck et al., 2014).

- Studies that have examined muscle fiber composition in hypertrophic jaw muscles show enlarged fibers with otherwise normal appearance, but varying results in fiber type distribution, frequency, and diameter. Histologically, muscle hypertrophy is often divided into reactive and nonreactive forms. In reactive masseter muscle hypertrophy due to excessive workload, progressive enlargement of the diameter of type II fibers with peripheral position of the nucleus is typically seen (Rokadiya and Malden, 2006). However, in a patient with temporalis muscle hypertrophy with a history of bruxism both type I and type II fibers were enlarged (>50 µm), but there was a predominance of type I fibers (Katsetos et al., 2014). In a patient with bilateral masseter hypertrophy, a decreased frequency of type I fibers, loss of type IIB, and increased frequency of type IIC, IIA, and IM were noted (Satoh et al., 2001). The authors of that study suggested that these changes were not caused by excessive workload, but rather were a result of compensatory enlargement due to lack of high-tetanus-tension type IIB fibers in this specific patient.

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses