Juvenile idiopathic arthritis (JIA) is a chronic childhood disease that can have a profound effect on growth and development of the facial skeleton. An understanding of the disease and its therapy is necessary before gathering the necessary data to plan therapy and subsequent medical and surgical treatment. This chapter reviews the current knowledge.

Etiopathogenesis

JIA affects an estimated 300,000 children in the United States and thus constitutes one of the five most common classes of chronic illness in childhood. Diagnosis depends on the medical history, physical examination, and elimination of other diagnoses. Inflammation needs to begin before the patient reaches the age of 16 years, and the symptoms must last from 6 weeks to 3 months with limitation of joint motion accompanied by heat, pain, or tenderness. There are no confirmatory blood tests. JIA is characterized by unpredictable flares during which children may experience an abrupt exacerbation of symptoms. Its effect on growth is multifactorial and includes not only the disease itself but also side effects of medications, altered nutrition, and mechanical problems. Local growth disturbances occur as a result of inflammation and the accompanying increase in vascularity, which may result in either overgrowth or undergrowth of the affected site. In the maxillofacial region, micrognathia, malocclusion, facial asymmetry, and limited mouth opening are known common sequelae. They result mainly from changes in vascularization and destruction of a growth site in the mandibular condyle.

Many names have been ascribed to the pediatric type of chronic arthritis, including juvenile rheumatoid arthritis (JRA), juvenile chronic arthritis (JCA), and JIA. Although JIA is used by most specialists in pediatric rheumatology, other terms, especially JRA, are more common among non-specialist in the United States. There are several subtypes of JIA:

- •

Oligoarticular pauciarticular: involves fewer than five joints in its first stages and affects about half of all children with arthritis.

- •

Polyarticular: affects five or more joints and can begin at any age.

- •

Systemic onset: affects about 10% of children. It begins with repeating fevers with temperatures that can be 103° F or higher and is often accompanied by a pink rash that comes and goes. It may cause inflammation of the internal organs, as well as the joints. Joint swelling may not appear until months or even years after the fevers begin. Anemia and elevated white blood cell counts are also typical findings.

- •

Psoriatic arthritis: children have both arthritis and psoriasis or a strong family history of psoriasis.

- •

Enthesitis-related arthritis: a form of JIA that often involves the attachments of ligaments, as well as the spine. It is sometimes called a spondyloarthropathy.

Pathologic Anatomy

The most important growth site of the mandible is located in the head of the condyle. Early destruction of its fibrocartilage cap can seriously affect mandibular development. Asymmetry between the two condyles is a common finding in JIA, especially at the onset of the disease.

The relationship between condyle-ramus height, expressed as the condylar ratio, is significantly smaller in children with JIA than in unaffected children with class I or class II malocclusion. The maxilla tends to be smaller in vertical dimensions and is also posteriorly rotated. This can be explained as a reaction to the decreased growth of the mandible or, alternatively, altered loading on the posterior regions of the maxilla.

In patients with unilateral condylar destruction, asymmetry develops with the chin deviating to the affected side and resulting in a shorter vertical dimension on the affected side. A higher degree of mandibular retroposition and smaller mandibular dimensions are found in children with complete destruction of the head of the condyle than in those with partial destruction. Solow and Kreiborg suggested that lack of forward growth of the mandible initiates increased extension of the head in relation to the cervical column to maintain an adequate airway ( Fig. 101-1 ).

They proposed that this increased extension results in soft tissue stretching, which also has a restraining effect on facial development. It is also clear that earlier onset, long duration, and the degree of severity of the disease are directly correlated to extent of the maxillofacial abnormalities. Interestingly, Stabrun and colleagues found reduced mandibular growth in affected children without visible condylar lesions. It is likely that early inflammatory alterations that did not cause any changes on conventional radiography have occurred in the jaw joints of these children. This further underlines the need to consider the use of magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) when jaw growth lags.

Other soft tissue structures that are affected by this disease process are the muscles of mastication. Maximum molar bite force is reduced in children with JIA to about 60% of that recorded in healthy children. This in turn can influence craniofacial morphology during growth.

Pathologic Anatomy

The most important growth site of the mandible is located in the head of the condyle. Early destruction of its fibrocartilage cap can seriously affect mandibular development. Asymmetry between the two condyles is a common finding in JIA, especially at the onset of the disease.

The relationship between condyle-ramus height, expressed as the condylar ratio, is significantly smaller in children with JIA than in unaffected children with class I or class II malocclusion. The maxilla tends to be smaller in vertical dimensions and is also posteriorly rotated. This can be explained as a reaction to the decreased growth of the mandible or, alternatively, altered loading on the posterior regions of the maxilla.

In patients with unilateral condylar destruction, asymmetry develops with the chin deviating to the affected side and resulting in a shorter vertical dimension on the affected side. A higher degree of mandibular retroposition and smaller mandibular dimensions are found in children with complete destruction of the head of the condyle than in those with partial destruction. Solow and Kreiborg suggested that lack of forward growth of the mandible initiates increased extension of the head in relation to the cervical column to maintain an adequate airway ( Fig. 101-1 ).

They proposed that this increased extension results in soft tissue stretching, which also has a restraining effect on facial development. It is also clear that earlier onset, long duration, and the degree of severity of the disease are directly correlated to extent of the maxillofacial abnormalities. Interestingly, Stabrun and colleagues found reduced mandibular growth in affected children without visible condylar lesions. It is likely that early inflammatory alterations that did not cause any changes on conventional radiography have occurred in the jaw joints of these children. This further underlines the need to consider the use of magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) when jaw growth lags.

Other soft tissue structures that are affected by this disease process are the muscles of mastication. Maximum molar bite force is reduced in children with JIA to about 60% of that recorded in healthy children. This in turn can influence craniofacial morphology during growth.

Diagnostic Studies

The role of imaging has changed over time from not only demonstrating destruction of various portions of the stomatognathic system but also identifying changes with MRI before they are noticeable clinically. It can detect synovial proliferation and joint effusion preceding the development of cartilage destruction and bone erosion. Muller and co-workers found that 63% of their cohort of patients with JIA had involvement of the temporomandibular joint (TMJ) demonstrated when MRI was used with a single dose of gadolinium-based contrast medium. This in turn allows initiation of appropriate therapies at an earlier date with a resultant reduction in condylar destruction.

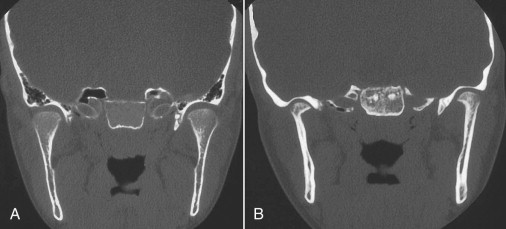

The most common conventional radiographic signs of arthritis of the TMJ are erosion and flattening of the condyle ( Fig. 101-2 ). This ranges from small erosions on the superior bony surface to almost complete absence of the condylar head. Changes affect the condylar head much more frequently than the glenoid fossa. Reduction of the joint space, anterior displacement of the condyle in the fossa, osteophyte formation, subchondral cysts, and restricted translatory movement have also been described.

Panoramic radiographs and computed tomography (CT) show a higher incidence of lesions in children with polyarticular onset than in those with pauciarticular or systemic-onset types.

Medical Treatment

The overall treatment goal is to control symptoms, prevent joint damage, and maintain function. Children with polyarticular JIA whose joint swelling persists and who test positive for rheumatoid factor are more prone to the development of joint damage and may require more aggressive treatment.

The first line of treatment involves a non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID) such as ibuprofen (Motrin or Advil) or naproxen (Naprosyn) administered in a dose appropriate for the child. Younger children may be given liquid preparations or medications that require less frequent use. NSAIDs can cause gastrointestinal distress and should be taken with food.

Disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (DMARDs) are added as a second-line treatment when the arthritis does not respond to NSAIDs. DMARDs include hydroxychloroquine (Plaquenil), sulfasalazine (Azulfidine), methotrexate (Rheumatrex), and more recently developed medications known as biologics, which include “anti–tumor necrosis factor agents.” Nonetheless, because of consistent performance, methotrexate is still considered the “gold standard” against which all other agents are compared.

Control of the disease is of utmost importance when planning surgery because continued destruction of the mandibular condylar growth sites must be arrested before embarking on surgical-orthodontic treatment. This needs to be emphasized to the treating physician, the patient, and the immediate family.

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses