The purpose of this article is to report the orthodontic treatment of a patient with extremely delayed development of the maxillary lateral incisors. At 7 years of age, the boy’s permanent maxillary lateral incisors had not erupted. A radiograph showed no tooth germs in place, although well-defined radiolucent areas were evident. Removal of the radiolucent areas was contemplated, but it was rejected in favor of a conservative approach. At age 13, peg-shaped maxillary lateral incisors erupted; they were positioned during orthodontic treatment and reshaped with composite restorations, providing good esthetics and function.

Normal tooth development can be disrupted by genetic and environmental factors that might lead to dental anomalies in number, size, and shape. Hypodontia is a relatively frequent tooth-number anomaly. Its prevalence depends largely on the population studied, ranging from 0.03% to 10.1%. Lateral incisors and second premolars are the most frequently absent teeth in the permanent dentition, when third molars are excluded. Peg-shaped or small lateral incisors are considered a variable expression of the same gene that causes hypodontia, and their association with other anomalies has been reported. Hypodontia of the lateral incisors has been found in 32.1% of patients with fused deciduous teeth.

Since anomalies of size, number, and shape often require space management, patients with these conditions are frequent orthodontic patients. A diagnosis of hypodontia or aplasia of permanent teeth requires careful examination of the radiographic images and the follow-up of suspected cases at early ages, with attention to tooth development chronology and its normal variations. Hypodontia has been associated with a delay of about 1.51 years in tooth development. However, since a 7-year delayed development of premolars has also been observed, it has been suggested that a definitive diagnosis of hypodontia of the premolars should be postponed until the age of 12 years. The calcification of another tooth frequently affected by agenesis, the maxillary permanent lateral incisor, begins about the age of 1 year. Its eruption occurs at age 8 years, with a variation of 1 year, and late calcification is uncommon.

In this article, we present the orthodontic treatment of a patient with an extreme delay of maxillary lateral incisor development that was followed until a more precise differential diagnosis could be made.

Diagnosis and etiology

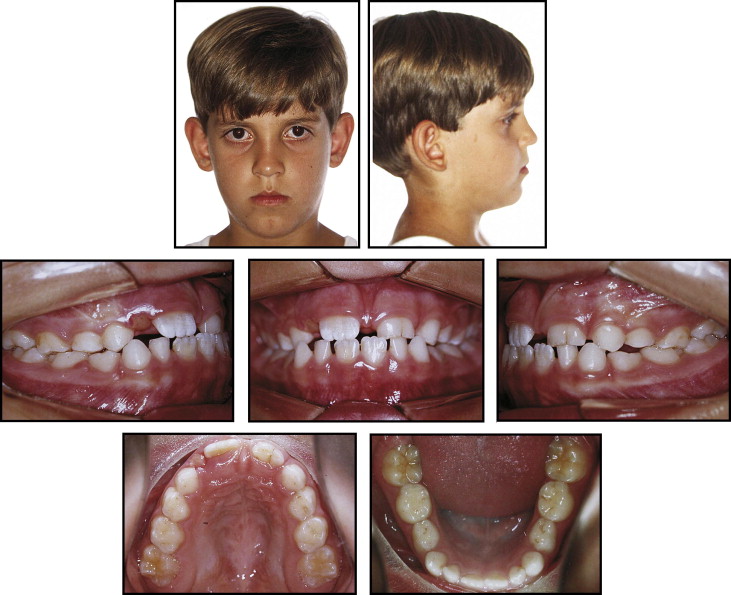

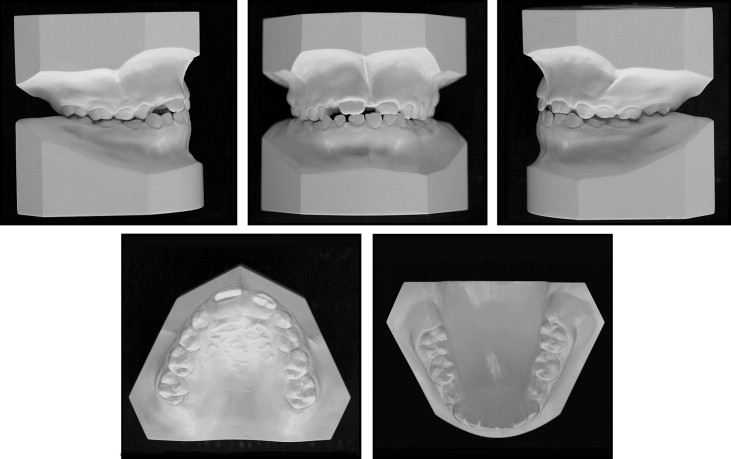

The patient was a 7-year-old boy whose parents’ main complaint was the delayed retention of the maxillary left central and lateral deciduous incisors. His facial profile was straight with good lip balance ( Fig 1 ). The patient was in the mixed dentition, with an Angle Class I molar relationship, the maxillary and mandibular right deciduous canines in crossbite, and a thick insertion of the maxillary labial frenum causing a space between the maxillary central incisors. The left central and lateral deciduous incisors were fused. There was no crowding in the mandibular arch ( Fig 2 ). Radiographic examination showed no root resorption of the fused left central and lateral deciduous incisors. The tooth germs of the maxillary right and left lateral incisors were absent, but well-defined radiolucent areas, that might resemble a tooth, were observed ( Fig 3 ). These radiolucent areas were in the path of eruption of the maxillary canines and could have prevented the eruption of these teeth. Cephalometric analysis showed a maxillary deficiency with a slight Class III tendency ( Fig 4 ; Table ).

| Measurement | Pretreatment 7 y 3 mo |

After phase 1 13 y 3 mo |

Posttreatment 15 y 11 mo |

|---|---|---|---|

| SNA (°) | 80 | 81 | 80 |

| SNB (°) | 79,5 | 83 | 82 |

| ANB (°) | 0,5 | −2 | −2 |

| Convexity angle (°) | 1 | −5 | −5 |

| Y-axis (°) | 56 | 54 | 54 |

| Facial angle (°) | 89 | 93 | 93 |

| SN-GoGn (°) | 31 | 31 | 32 |

| FMA (°) | 26 | 22 | 22 |

| IMPA (°) | 93 | 89 | 91 |

| U1.NA (°) | 31 | 35 | 31 |

| U1-NA (mm) | 7 | 10 | 10 |

| L1.NB (°) | 27 | 24 | 25 |

| L1-NB (mm) | 6 | 6 | 5 |

| 1.1 (°) | 123 | 123 | 125 |

| L1-APog (°) | 3 | 4 | 4 |

| UL-S (mm) | 1 | −1 | −1 |

| LL-S (mm) | 4 | 1 | 1 |

Treatment objectives

The treatment objectives were to improve the anteroposterior skeletal relationship between the maxilla and the mandible, use traction on the left central permanent incisor, surgically remove the labial frenum insertion, follow the occlusal development, and correct the molar relationship and the overjet.

Treatment objectives

The treatment objectives were to improve the anteroposterior skeletal relationship between the maxilla and the mandible, use traction on the left central permanent incisor, surgically remove the labial frenum insertion, follow the occlusal development, and correct the molar relationship and the overjet.

Treatment alternatives

The first option for treatment was the surgical removal of the 2 radiolucent areas and the maxillary labial frenum insertion. This would be followed by protraction facemask therapy and rapid palatal expansion.

The second option was not to remove the radiolucent areas immediately but follow their development. Meanwhile, the maxillary frenum insertion would be removed, and facemask therapy with rapid palatal expansion would be started. The surgical removal of the radiolucent areas would be postponed until a more precise differential diagnosis of odontoma or microdontia could be made.

Both treatment options would be followed by a second phase of treatment with fixed appliances. The objectives of the second phase would change according to the results of the first phase: ie, to open or close the spaces depending on the definitive diagnosis of the radiolucent areas.

The second option was chosen because, despite the patient’s age, the radiolucent areas resembled small teeth in an early developmental stage. Also, the possibility of using these teeth in the future as lateral incisors could avoid some problems involved in the treatment of missing lateral incisors.

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses