The health professions continuously consider their future, and the dental profession will be faced with important questions in the next few decades. Advances in material science and development of new surgical procedures provide solutions to clinical problems that were unavailable just a few years ago. Further, the esthetic desires of patients can be met in a fashion that can change a smile and have remarkably positive effects on a person’s appearance and self-image.

However, larger societal issues will impact the profession in the future, including provision of services to individuals who have difficulty accessing dental care, the introduction of mid-level providers, oral health care in health care reform, an increased need for oral health care for the elderly, and the position of the dental profession in the context of health care.

Over the next few decades, the patient population seen in dental offices will be aging. By 2030, 1 in 5 Americans will be at least 65 years of age. These individuals will be retaining all or most of their dentition, but will also be living with chronic diseases and will be managed with multiple medications over decades. The challenge is to provide appropriate dental care for these individuals in consideration of their general health status.

The finding that periodontal disease and periodontal inflammation can adversely influence the severity of certain diseases and disorders at distant sites has also changed our thinking about oral health in the context of general health. Studies examining the relationship of periodontal disease to disorders such as adverse pregnancy outcomes, diabetes mellitus, cardiovascular and cerebrovascular disease, and respiratory disease, as well as other less well-developed associations, have been published in the dental and medical literature. This has increased awareness by nondental health care providers of the potential importance of oral disease for patients seen in medical settings. The microbiota associated with periodontal disease have been identified in atheromas from the coronary arteries of patients with cardiovascular disease and periodontal bacteria have been identified as contributing to adverse pregnancy outcomes. The inflammation associated with periodontal disease has been implicated as contributing to poor metabolic control in patients with diabetes mellitus, and periodontal therapy reduces serum levels of C-reactive protein, a risk factor for coronary artery disease.

The possibility that periodontal disease is a risk factor for different chronic diseases represents a new health care linkage. Building on these associations, dental providers can be involved in the identification of patients with a disease who are unaware of their illness, risk factor reduction, and the assessment of patient compliance with their prescribed course of health care. As discussed in this volume, this can include identification/modification of risk factors for multiple diseases, including hypertension, smoking cessation and obesity management, identification of diseases such as diabetes mellitus, osteopenia/osteoporosis, infectious diseases including HIV and hepatitis C, and dermatological disorders.

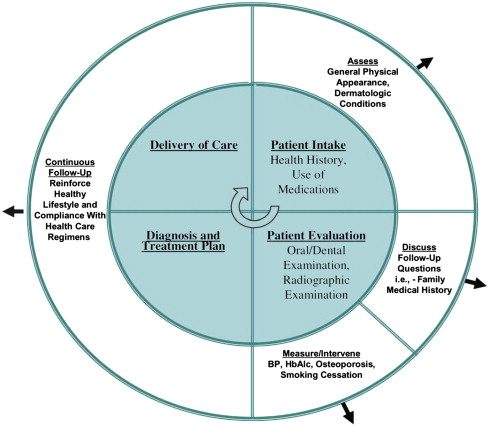

An approach to incorporating primary health care into dental practice has been proposed ( Fig. 1 ). Patient care in the dental office can be divided into 4 components (patient intake, patient evaluation, diagnosis and treatment planning, and delivery of care). Consideration of the patient’s general health would occur in all phases, including visual observation (during patient intake), questioning, follow-up, specific measurements and interventions (during patient evaluation), and continuous, long-term follow-up (during the diagnosis and treatment planning, and provision of care, phases).