Introduction

An impacted tooth is one that either fails to erupt into its nature position or one that is hindered from such eruption by adjacent teeth, dense bone, or an overgrowth of soft tissue. The treatment of impacted teeth is either removal of the obstructing hindrance or removal of the tooth itself.

The most common impacted tooth is the third molar or wisdom tooth. As a general rule, most human populations have 4 wisdom teeth; 2 upper and 2 lower. It is well acknowledged that wisdom teeth are the most commonly congenitally missing teeth and, as such, 10% of the US population has only 3, 8% only 2, and 2% only 1. Approximately 4% have complete agenesis of their wisdom teeth. It should be noted that more wisdom teeth are missing in the maxilla than from the mandible.

The third molar is characterized by variability of morphology, root type, time of formation, and time of eruption. Wisdom teeth formation begins between 3 and 4 years of age. Calcification starts at 7 to 10 years with crown completion between 12 and 16 years of age. Third molar eruption usually occurs in the age group of 17 to 21.

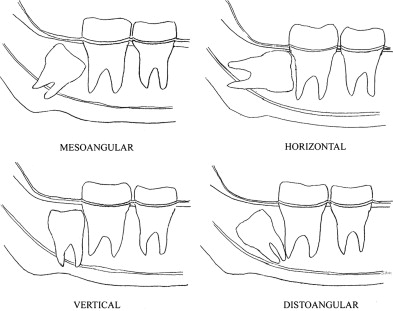

Impacted wisdom teeth are classically characterized by their position within the bone. This classification serves both the clinical presentation and the findings of imaging studies ( Fig. 1 ). Impacted wisdom teeth and their treatment are a major problem for dentistry today. Whether or not to remove these teeth is without a doubt one of the most difficult treatment decisions made by dentists in modern time.

Impacted, partially erupted, and fully erupted wisdom teeth can remain asymptomatic for many years but can ultimately cause acute pain, infection, tumors, cysts, caries, periodontal disease, and loss of adjacent teeth. In addition, there is literature describing relapse after orthodontic retention as well as orthodontic crowding being caused by retained or impacted wisdom teeth.

Tooth development

The primitive oral cavity is lined by an epithelial layer termed ectoderm. This ectoderm consists of a basal layer of columnar cells and a surface or covering layer of more flattened cells. From this epithelial layer, tooth buds form, which in time lead to the development of both primary and permanent teeth.

A tooth bud consists of 3 basic units: (1) enamel organ from which arises enamel; (2) the dental papilla, which in turn gives rise to dentin and the tooth pulp; and (3) the dental sac, which ultimately produces the cementum and periodontal ligament. The enamel organ is ectodermal, whereas both the dental papilla and dental sac are considered ectomesenchymal in origin.

At 2 to 4 weeks of gestation, the embryo develops a band of thickened epithelium termed the dental lamina, which actually forms the outline of the future dental arches. At points along this lamina, there are nodules formed of more active epithelium that press into the underlying mesenchyme. Each of these buds represents the origin of the 10 upper and 10 lower primary teeth.

As the bud progresses to grow, it invaginates deeper into the connective tissue and forms a “caplike” structure ( Fig. 2 ). The concavity of this cap represents the inner enamel epithelium, which is more columnar in nature, whereas the outer or convex portion of the cap is composed of more flattened outer enamel epithelium. The cells that lie between these 2 epithelium layers are larger and filled with mucoid material. This cell grouping is the stellate reticulum, which ultimately protects the more delicate enamel-producing cells. As this combined structure progresses in development, it is termed the enamel organ.

As the inner enamel epithelium becomes more organized, it in turn influences the underlying connective tissue to proliferate. As it does so, this connective tissue condenses and forms the dental papilla, which ultimately will form the dentin-producing odontoblasts.

Simultaneously, there is peripheral proliferation and condensation of the mesenchymal tissue surrounding the outer enamel epithelium and the dental papilla. This tissue becomes more organized as the embryo ages and ultimately becomes the more fibrous dental sac.

The dental sac, the enamel organ, and the dental papilla together are the formative tissues of the entire tooth.

As the epithelium continues to invaginate deeper into the mesenchymal tissue, the enamel organ becomes more “bell-like” in configuration. The inner enamel epithelium is now a single layer of tall columnar cells termed ameloblasts. These ameloblasts exert an influence on the adjacent mesenchymal cells, which in turn differentiate into odontoblasts. As a result, these 2 layers begin formation of the enamel and dentin respectively ( Fig. 3 ). During this time, the original dental lamina proliferates and becomes the formative enamel organ of the permanent tooth buds.

Root development begins after enamel/dentin production reaches the cemento-enamel junction. The remaining inner and outer enamel epithelium together become the Hertwig epithelial root sheath and once again induce the mesenchymal tissue to begin formation of the root dentin. Simultaneously, the mesenchymal tissues of the dental sac differentiate into cementoblasts and produce cementum that covers the root dentin. After cementum production is complete, the root apex closes and tooth development is complete.

It is well acknowledged that many of the tissues leading to tooth development are also responsible for the various odontogenic cysts and tumors. Remaining epithelial rests of both the dental lamina and Hertwig root sheath can give rise to the dentigerous, primordial, and lateral periodontal cysts as well as tumors, such as the ameloblastoma and the keratocystic odontogenic tumor. Dental lamina within the gingiva also gives rise to gingival cysts and the peripheral ameloblastoma. The odontogenic myxoma and fibroma are presumed to arise from tissues of the dental papilla, and various fibro-osseous tumors take their origin from the tissues of the dental sac.

Tooth development

The primitive oral cavity is lined by an epithelial layer termed ectoderm. This ectoderm consists of a basal layer of columnar cells and a surface or covering layer of more flattened cells. From this epithelial layer, tooth buds form, which in time lead to the development of both primary and permanent teeth.

A tooth bud consists of 3 basic units: (1) enamel organ from which arises enamel; (2) the dental papilla, which in turn gives rise to dentin and the tooth pulp; and (3) the dental sac, which ultimately produces the cementum and periodontal ligament. The enamel organ is ectodermal, whereas both the dental papilla and dental sac are considered ectomesenchymal in origin.

At 2 to 4 weeks of gestation, the embryo develops a band of thickened epithelium termed the dental lamina, which actually forms the outline of the future dental arches. At points along this lamina, there are nodules formed of more active epithelium that press into the underlying mesenchyme. Each of these buds represents the origin of the 10 upper and 10 lower primary teeth.

As the bud progresses to grow, it invaginates deeper into the connective tissue and forms a “caplike” structure ( Fig. 2 ). The concavity of this cap represents the inner enamel epithelium, which is more columnar in nature, whereas the outer or convex portion of the cap is composed of more flattened outer enamel epithelium. The cells that lie between these 2 epithelium layers are larger and filled with mucoid material. This cell grouping is the stellate reticulum, which ultimately protects the more delicate enamel-producing cells. As this combined structure progresses in development, it is termed the enamel organ.

As the inner enamel epithelium becomes more organized, it in turn influences the underlying connective tissue to proliferate. As it does so, this connective tissue condenses and forms the dental papilla, which ultimately will form the dentin-producing odontoblasts.

Simultaneously, there is peripheral proliferation and condensation of the mesenchymal tissue surrounding the outer enamel epithelium and the dental papilla. This tissue becomes more organized as the embryo ages and ultimately becomes the more fibrous dental sac.

The dental sac, the enamel organ, and the dental papilla together are the formative tissues of the entire tooth.

As the epithelium continues to invaginate deeper into the mesenchymal tissue, the enamel organ becomes more “bell-like” in configuration. The inner enamel epithelium is now a single layer of tall columnar cells termed ameloblasts. These ameloblasts exert an influence on the adjacent mesenchymal cells, which in turn differentiate into odontoblasts. As a result, these 2 layers begin formation of the enamel and dentin respectively ( Fig. 3 ). During this time, the original dental lamina proliferates and becomes the formative enamel organ of the permanent tooth buds.

Root development begins after enamel/dentin production reaches the cemento-enamel junction. The remaining inner and outer enamel epithelium together become the Hertwig epithelial root sheath and once again induce the mesenchymal tissue to begin formation of the root dentin. Simultaneously, the mesenchymal tissues of the dental sac differentiate into cementoblasts and produce cementum that covers the root dentin. After cementum production is complete, the root apex closes and tooth development is complete.

It is well acknowledged that many of the tissues leading to tooth development are also responsible for the various odontogenic cysts and tumors. Remaining epithelial rests of both the dental lamina and Hertwig root sheath can give rise to the dentigerous, primordial, and lateral periodontal cysts as well as tumors, such as the ameloblastoma and the keratocystic odontogenic tumor. Dental lamina within the gingiva also gives rise to gingival cysts and the peripheral ameloblastoma. The odontogenic myxoma and fibroma are presumed to arise from tissues of the dental papilla, and various fibro-osseous tumors take their origin from the tissues of the dental sac.

Adverse conditions arising from retained wisdom teeth

Tooth formation evolves continuously throughout the first 2 decades of life. As the wisdom teeth are the last permanent teeth to enter the oral cavity, many times these teeth have no space remaining in which to completely erupt. In such cases, wisdom teeth, or third molars, are termed “impacted teeth” and as such are retained or at least partially retained with in the bony or soft tissue confines of the upper and/or lower jaw. Several pathologic conditions can be initiated by this tooth retention. Inflammatory, mechanical, and neoplastic conditions can and do arise when the wisdom teeth remain impacted, partially erupted, or fully erupted. These adverse situations can be quite diverse in origin as well as their clinical presentation.

Pericoronitis and related infections

Pericoronitis is a localized infectious process usually involving mandibular third molars ( Fig. 4 ). It is the most common acute inflammatory disease that occurs with retention of wisdom teeth. The usual clinical scenario is, first, the crown of a partially erupted lower wisdom tooth becomes incompletely covered by the adjacent oral soft tissue (operculum). Food then becomes lodged beneath this operculum. The resultant soft tissue pocket is then invaded by oral bacteria with a resultant localized infection ensuing ( Fig. 5 ). Patient complaints range from pain and swelling to trismus and fever.

Pericoronitis ranges from a mild form with only localized swelling to a more aggressive form involving a greater amount of adjacent soft tissue. Pericoronitis in its most severe form can allow the localized bacterial infection to become generalized and then spread along the fascial spaces of the head and neck causing extensive tissue involvement with trismus and abscess/cellulitis formation. If left untreated, many of the acute infections become chronic and can often progress into osteomyelitis as the infectious process invades the medullary and cortical bone.

Seasonal variations associated with acute pericoronitis are readily seen, with the peak time being in the spring and fall. This problem appears to reach its lowest level in the winter months. Such differences are difficult to explain but may be related to environmental conditions and their effect on the normal oral flora.

There is no major sex bias in pericoronitis, with females affected only slightly more commonly. Younger people between the ages of 18 and 25 appear to represent the most common groupings of occurrence. Divergent standards of dental care is the most likely reason that pericoronitis occurs commonly in higher socioeconomic groups. Lesser groups often lose teeth much earlier and thus leave space in the dental arch allowing wisdom teeth to completely erupt. Mesioangular impactions are the type most commonly involved with pericoronitis. This is followed by distoangular, vertical, and then horizontal impacted wisdom teeth. Neither the left nor the right side is favored.

Pericoronitis continues to linger and smolder unless treated either symptomatically or by removal of the offending tooth. Most patients left with untreated pericoronitis will suffer at least 2 and often more flare-ups, which can occasionally last up to 21 days. Rarely, a patient must be hospitalized for either a progression of the infection or for intravenous fluid administration.

Initial treatment of pericoronitis involves debriding the pocket beneath the operculum with an irrigating solution. This irrigation removes not only the offending food particles but also decreases the bacterial count in the area. Occasionally, an operculectomy may be of benefit. More severe cases may need surgical incision and drainage, as well as parenteral antibiotics and possibly hospitalization.

After a single episode of pericoronitis, the wisdom tooth should be removed as soon as possible to prevent recurrent and possibly more severe infections. Some literature describes an increased incidence of alveolar osteitis (dry socket) if the tooth is removed during an acute episode of pericoronitis; thus, many clinicians choose to wait until the area of the pericoronitis has subsided. Other studies rebuke this thought and stress immediate removal of the offending wisdom tooth.

Orthodontic treatment

For many years, impacted wisdom teeth have been implicated as a leading cause of anterior dental crowding both before and after orthodontic treatment. Despite numerous articles describing the role of wisdom teeth in the development of such malocclusions, the issue remains controversial. In addition, according to several written surveys, there appear to be significant differences between the opinion of orthodontists and oral and maxillofacial surgeons with regard to this problem.

Several theories discuss the mechanism of anterior dental crowding. These include anterior directed pressure from impacted or erupting wisdom teeth; a persistent mesial and occlusion drift of the entire dental arch; contraction and maturation of periodontal soft tissue, specifically the trans-septal periodontal fibers; overexpansion of the dental arches during orthodontic treatment; and the containment of the mandibular arch by the maxillary teeth. Each of these theories has been studied extensively but not one proposed cause has proven to be the driving force behind anterior dental crowding ( Fig. 6 ).

A voluminous amount of anecdotal data has been internationally presented by oral and maxillofacial surgeons, orthodontists, pediatric dentists, and general dentists alike. Each specialty group often relates their own personal biases surrounding the removal and nonremoval of asymptomatic wisdom teeth. All groups approve the removal of symptomatic teeth, but the consideration of removing asymptomatic wisdom teeth varies greatly with the specific specialty group involved.

The available literature addressing the removal of asymptomatic wisdom teeth to prevent anterior dental crowding still remains quite controversial. Significant disagreement among practitioners regarding the fundamental issues underlying this controversy continues today. Of all the specialty groups, oral and maxillofacial surgeons are more likely to believe that the removal of asymptomatic wisdom teeth decreases the likelihood of anterior dental crowding. Orthodontists as a whole, but particularly the younger and the more recent residency graduates, are much less likely to subscribe to this theory. Both groups believe that if the possibility of wisdom teeth causing anterior crowding exists, the mandibular teeth are the more likely culprits as opposed to the maxillary wisdom teeth.

Odontogenic cysts

Cystic lesions of the jaws constitute one of the most frequently encountered entities associated with impacted or unerupted wisdom teeth. The literature is divided on the findings of such occurrences, with most published material reporting a 1% to 6% incidence. Other articles claim that this cyst development has been greatly exaggerated or overemphasized.

Very few epithelial-lined cysts occur in bones other than those of the jaws and facial skeleton. The cysts that arise in these areas are considered either developmental or inflammatory. The most common inflammatory cyst is the periapical cyst arising from a nonvital tooth, whereas the dentigerous cyst is by far the most commonly occurring developmental odontogenic cyst.

The dentigerous cyst is always associated with an impacted or unerupted tooth; most commonly a third molar or wisdom tooth. This cyst arises when the follicle separates from the developing tooth. Clinically, the cyst surrounds the crown of the impacted tooth. The epithelial lining of the cyst most likely arises from the reduced enamel epithelium of the developing tooth, although some consideration is given to the premise that occasionally dentigerous cysts arise from remnants of Hertwig epithelial root sheath or the rests of Malassez ( Fig. 7 ).