Webster’s New World Medical Dictionary defines complication as “an additional problem that arises following a procedure, treatment or illness and is secondary to it. A complication complicates the situation.”

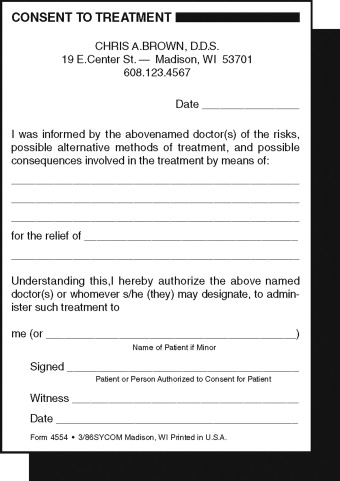

Exodontia is the most common procedure performed by oral maxillofacial surgeons. According to a report by the Public Health Service, “… more than three-quarters of the total cost of payments for oral surgery procedures were allocated to removal of third molars.” It stands to reason that most of the complications we see are related to exodontia. These can be common or rare and can occur during or after treatment. Nevertheless, with careful treatment planning and adhering to good surgical techniques and principles, surgeons can minimize the frequency of complications. In addition, early recognition and proper management can help to improve the outcome of procedures. Considering the fact that complications are a risk and potential sequelae of any surgery, it is imperative that surgeons notify patients of them while obtaining informed consent ( Box 12-1 ). Complications can occur even when the surgeon adheres to good surgical principles. Variations in anatomy and the patient’s response to healing can result in complications even when the surgeon executes the surgical procedure within the standard of care.

Complications during exodontia:

- 1.

Removal of the wrong tooth

- 2.

Injuries to teeth and adjacent structures

- 3.

Residual root remnants

- 4.

Displacement of teeth or root tips

- 5.

Soft tissue injuries

- 6.

Oroantral communications

- 7.

Swallowing or aspiration of teeth, fragments of teeth, or restorations and crowns

- 8.

Tissue emphysema

- 9.

Sensory nerve injuries

Complications after exodontia:

- 1.

Alveolar osteitis (dry socket)

- 2.

Infection

- 3.

Trismus, swelling, and pain

- 4.

Temporomandibular joint problems

Complications that can occur during or after exodontia:

- 1.

Hemorrhage

- 2.

Injuries to osseous structures

▪

COMPLICATIONS DURING EXODONTIA

REMOVAL OF THE WRONG TOOTH

One of the most frequent complications occurring during exodontia is the wrongful extraction of teeth. Common causes include: miscommunication between the referring dentist and his office personnel with the specialist’s office, incorrectly labeled radiographs or referral slips, and disagreement between the dentist and the patient. A careful history with a review of recent radiographs and a thorough clinical examination is the best way to prevent this complication. In the event of the inadvertent removal of the wrong tooth, if discovered at the time of surgery, the tooth should be implanted immediately and stabilized if it is a healthy salvageable tooth. The patient should be given antiinfectives and informed of the event and instructed to return for follow-up care. If the patient has a referring dentist, he or she should also be made aware of what occurred. The event should be carefully documented in the patient’s chart.

INJURIES TO TEETH OR ADJACENT STRUCTURES

Fractures and loosening of adjacent teeth and dislodging of large restorations or crowns can accidentally occur during exodontia. Careful evaluation of the surrounding dentition and radiographs should be done before instituting treatment. Often this complication is unavoidable because of loose crowns or large restorations with recurrent decay under the restoration. The patient should be made aware of the potential for these events occurring ( Figures 12-1 and 12-2 ). If teeth are partially avulsed during removal of adjacent teeth, they should be repositioned and stabilized. Any dislodged crowns from teeth that do not show signs of decay can be permanently recemented. Those teeth under crowns with decay should be reinserted with temporary cement, and the general dentist should be informed of the event. Adjacent teeth that are fractured or that have large restorations dislodged should be temporized. The patient should be referred back to their general dentist for definitive treatment. The incident should be well documented in the patient’s chart, and they should be made aware of the problem.

RESIDUAL ROOT REMNANTS

During exodontia, roots can fracture often in spite of good surgical technique. Usually this occurs because the root is dilacerated or divergent. If the remnant is a couple of millimeters in diameter and in close proximity to a vital structure, such as a nerve or the sinus, risks versus benefits should be considered. Usually a root remnant this size will be of no consequence if not grossly infected. If a decision is made to leave it, the patient should be informed, postoperative radiographs should be taken, documentation should be entered in the patient’s chart, and they should be evaluated periodically both clinically and radiographically to ensure uneventful healing.

DISPLACEMENT OF TEETH AND ROOT TIPS

Displacement of teeth and root tips is a rare occurrence. Some causative factors that have been implicated are the inexperience of the surgeon, uncontrolled force, improper use of instrumentation, and difficult access with poor visualization and inadequate exposure. Variations in anatomy, such as a thin lingual plate of bone in the mandibular molar area of the maxillary sinus wall extending between the roots of the maxillary molars, can increase the potential for the displacement of teeth or root tips into the floor of the mouth or maxillary sinus respectively.

The sites most frequently involved are the maxillary sinus, the submandibular space, and the infratemporal fossa. Some reports describe an accidental displacement of a third molar into the lateral pharyngeal space.

Displacement of root tips or impacted teeth into the maxillary sinus or infratemporal fossa usually occurs because of the close proximity and thinness of the sinus floor or wall. In removing a superiorly distally impacted third molar, adequate bone removal, good visibility with careful elevation, and a distal stop is a must. If inadvertently a tooth or root tip is dislodged into the sinus, an attempt should made to retrieve it through the extraction site with a suction tip. If the attempt is unsuccessful, radiographs should be taken to localize the tooth and a Caldwell Luc approach should be used to remove it. When a third molar is displaced into the infratemporal fossa, radiographs must be obtained to localize its position, the incision should be extended posteriorly to the tonsillar fauces, and with careful blunt dissection, an attempt should be made to identify and remove it. Care must be taken to prevent injury to the pterygoid plexus of veins, which can result in brisk bleeding. If this happens, the procedure should be aborted and fibrosis should be allowed to develop around the tooth, from several days to several weeks. An attempt can be made to remove it by a hemicoronal or an intraoral approach after CT analysis to determine its location. Some authors recommend careful follow-up if the patient is asymptomatic. One report indicated no adverse affects after 15 months. Care should be taken in attempting to remove the distal roots of third molars because the lingual cortex of the mandible curves laterally and is thin in this area. When a root tip is displaced into the sublingual space, an attempt should be made to palpate it digitally and push it back into the socket. If this is unsuccessful, a full flap should be raised on the lingual and the mylohyoid muscle dissected free from its attachment trying to keep the tip in position to prevent further displacement and, thus, facilitate its removal. It is not often that a root becomes displaced deep into the submandibular area. If this should occur, fibrosis should be allowed to take place, and if removal is necessary, an extraoral approach can be used to retrieve it.

Infrequently, roots are pushed through thin cortical plates in the maxillary bicuspid and molar areas. Usually, they can be palpated subperiosteally and can be pushed back through the socket, or an incision can be made below it to remove it.

Some reports describe accidental displacement of third molars into the lateral pharyngeal space. Care must be taken with the use of surgical instruments to avoid such untoward effects during exodontia.

SOFT TISSUE INJURIES

Soft tissue injuries can occur when performing exodontia. Soft tissue injuries include laceration of the flap, burns, abrasions, puncture wounds, and subcutaneous emphysema.

Lacerations of the flap can be caused by too small of a flap and overretraction. These tears can increase the chance of wound dehiscence and delay healing. If a tear does occur, the margins should be reapproximated and carefully sutured. Excising the edges before closure is indicated if the tear is jagged. Designing larger flaps with releasing incisions and using less retraction can prevent this complication.

Burns and abrasions are caused by rotary drills. Careful attention is a must when using them. One must avoid catching the soft tissue with the shank of the bur and creating a laceration. This usually occurs with the buccal mucosa and the corner of the mouth. The use of a bur guard helps in preventing this problem. These burns and/or abrasions are quite painful and are slow to heal. Applying antiinfective ointment or silver sulfadiazine treats these burns and/or abrasions. This complication can be prevented by careful attention of the assistant to the location of the shank of the bur when the surgeon is cutting. Maintenance of the bur guard is important to prevent its overheating, which can cause severe burns to the lip.

Puncture wounds to the soft tissue can be the result of uncontrolled forces with sharp instruments, such as a periosteal or a straight elevator. This can be prevented by using finger rest support from the opposite hand to protect the area from potential slippage with an instrument. Small puncture wounds should be left open and not sutured once hemostasis is achieved. If hemostasis cannot be achieved, sutures may be necessary. Because the instrument that punctured the soft tissue could contain debris and bacteria, the patient should be placed on antiinfectives.

OROANTRAL COMMUNICATION

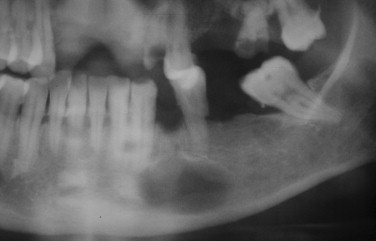

Exposure of the maxillary sinus can occur while extracting maxillary molars. Proper radiographic evaluation will usually alert you to the fact that this may be a possibility. The morphology of the roots should also be considered ( Figure 12-3 ). Widely divergent roots increase the chance that the sinus floor could be removed along with the tooth. If the tooth roots have close proximity to the sinus, less force should be used, and division of the roots should be considered.

Oroantral communication is an important complication to discuss with the patient when receiving an informed consent for the removal of a maxillary molar. If this occurs, appropriate treatment is necessary to prevent a postoperative maxillary sinusitis and formation of a chronic oroantral fistula.

If the maxillary sinus is exposed during extraction, treatment is determined by the size of the communication. Probing the communication is not advised. This could further tear the membrane. For small communication less than 2 mm, a collagen plug can be placed in the socket. This will help maintain a good blood clot. The patient needs special postoperative sinus instructions advising them not to sneeze, smoke, rinse, spit, suck on a straw, or blow their nose.

For moderate size communications (2 to 6 mm), a collagen plug can be placed with figures-of-eight sutures over the socket to prevent the plug from being dislodged. The patient should be given the postoperative sinus instructions. A 1-week course of antiinfectives, antihistamines, and nasal decongestants should be given. Usually, Augmentin, clindamycin, or a cephalosporin can be prescribed to decrease the possibility of a maxillary sinusitis.

For a large communication (greater than 6 mm), the sinus communication must be closed primarily using a flap procedure. A buccal or lingual flap may be necessary to close these large communications. Close follow-up is necessary for these patients.

SWALLOWING OR ASPIRATION OF TEETH, FRAGMENTS OF TEETH, OR RESTORATIONS AND CROWNS

During exodontia, it is advisable to place an oral drape to prevent swallowing or aspiration of loose teeth, dislodged crowns or fragments of teeth, root tips, or dental restorations. In the event of a foreign body being swallowed, the patient should be sent to the hospital for radiographs to localize it. The patient should then ensure passage. If a tooth, root tip, or other foreign body is aspirated during surgery and it becomes lodged in the trachea, methods used in Advanced Cardiac Life Support, such as the abdominal thrusts, back slaps, or the Heimlich maneuver, should be used in an attempt to remove it. If the patient becomes unconscious, an attempt should be made to remove it with a laryngoscope and a McGill forceps, or an emergency coniotomy should be attempted. In the event it passes the vocal cords, it will most likely enter the right main stem bronchus or the right lung. The patient should be transported to the hospital where an emergency bronchoscopy can be performed to remove the object. A detailed description of the event should be recorded in the patient’s chart.

TISSUE EMPHYSEMA

Tissue emphysema is a complication that is seen less frequently since the use of rotary instruments, such as the Hall drill and electric hand pieces. It is caused by the inclusion of air under pressure into the subcutaneous soft tissue. During the removal of bone or the sectioning of teeth with an air driven dental hand piece, air is forced subcutaneously resulting in a rapid onset of swelling. Other causes could be the use of an air syringe and a patient coughing or sneezing when a large flap is elevated.

When palpated there is a feeling of crepitus and occasionally some tenderness associated with it. Radiographs can show air in the soft tissue adjacent to the surgical site. Extensive subcutaneous emphysema can be life threatening or result in an infection leading to meningitis or mediastinitis.

Treatment consists of ice application to the affected site, systemic antiinfectives, and monitoring. The condition usually resolves in several days; however, severe cases may require hospitalization and IV antiinfectives.

SENSORY NERVE INJURIES

Sensory nerve injuries can occur with the removal of teeth whose roots are close to the inferior alveolar nerve, lingual nerve, and mental nerve. Temporary or permanent sensory nerve disturbances can occur anywhere from 0.4% to 2% of the time. It is important for the surgeon to obtain a detailed informed consent from their patients concerning these complications. The incidence of sensory nerve injuries from third molar surgery is related to many factors. Tooth proximity to the inferior alveolar nerve canal and variation in the anatomic relation of the lingual nerve to the crown of the mandibular third molar are major factors that contribute to nerve injuries.

A higher incidence of nerve injuries occurs with the removal of horizontally impacted teeth compared with mesioangular or distoangular impacted third molars ( Figure 12-4 ). The depth of the impaction, presence of completely developed roots, use of rotary instruments, and sectioning of teeth can all contribute to nerve injuries. Division of the inferior alveolar nerve is infrequent, but pressure and compression of the nerve can take place during the removal of the third molar. Neurosensory alteration of the inferior alveolar nerve can occur when normal intraoperative and postoperative hemorrhage occurs and extends into the mandibular canal. Because this is a rigid osseous structure and the nerve is confined within this canal, the accumulation of blood within the canal can cause a compressing nerve injury. Usually the neurosensory alteration will be temporary, but it can be permanent. Injury to the lingual nerve occurs either during the reflection of the flap, fracture of the lingual cortical plate, or perforation of the lingual cortical plate during sectioning of the tooth. The path of the lingual nerve as it passes on the lingual surface of the mandible near the mandibular third molar is variable. In approximately 17% of cases, the nerve lies above the crest of lingual bone and can be adherent to the follicle of the third molar. Therefore in these cases, a stretch injury or even a transection of the nerve can occur when the surgeon has performed the extraction technique within the standard of care.

The mental nerve can be injured during the removal of a premolar or during flap development or retraction. In the event of a high risk for nerve injury, the use of partial odontectomy may be indicated ( Figure 12-5 ). Seddon and Sunderland developed classifications for nerve injuries. The Seddon classification is based on time from injury and degree of recovery. It includes neurapraxia, axonotmesis, and neurotmesis. Sunderland expands his classification to include first degree (neurapraxia), second degree (axonotmesis), third degree, fourth degree, and fifth degree (neurotmesis).

Neuropraxis results from minor nerve compression or traction injury. Since there is no loss of axonal continuity usually there is complete recovery within 2 months. Microsurgery is not indicated. Axonotomesis is produced by blunt trauma, crushing, or a severe traction injury. Continuity of the axon is disrupted but not the epineurial sheath. Thus sensory recovery can takes 2 to 6 months, though some cases have taken 1 year. Microsurgery is not indicated unless a foreign body is associated with it.

Sunderland’s third- and fourth-degree nerve injury is the result of a compression, crush, or chemical injury. There can be some spontaneous recovery but not completely with a possible poor outcome. Microsurgery may be indicated if there is no improvement after 3 to 6 months. It should be emphasized that as long as the patient is exhibiting signs of improvement, microsurgery should be delayed.

Neurotmesis is the result of a complete transection of the nerve. The prognosis for spontaneous recovery is poor. Microsurgery is indicated for these injuries. Neurosensory testing should include two-point discrimination, light touch, brush strokes, vibrational sense, pain stimuli, and thermal discrimination. This will help determine the injury classification and recommended treatment. Nerve repairs should be performed by surgeons proficient in microsurgery for the best results.

▪

COMPLICATIONS AFTER EXODONTIA

ALVEOLAR OSTEITIS (DRY SOCKET)

Dry socket, or alveolar osteitis, is one of the more common surgical complications seen postoperatively. Some studies have shown the incidence to be as low as 3% with all extractions. , Other studies in the literature place the incidence of dry socket in the removal of mandibular third molars as high as 30%. Dry sockets rarely occur in the maxillary. Although the cause is not known, data suggests that saliva with a high bacterial count may be the etiologic factor in causing destruction or malformation of the blood clot after extractions. Other theories suggest fibrinolytic action as a possible cause because the use of antifibrinolytic agents demonstrated a decreased incidence of occurrence. Additional factors that may be responsible for dry sockets occurring are smoking, oral contraceptives, experience of the surgeon, complexity of the extraction, and poor oral hygiene.

The symptoms of a dull throbbing pain usually present themselves around the third to fifth day after surgery and are often confused with an earache, headache, or pain from another tooth with no evidence of pathologic condition. Narcotic analgesics tend not to give relief as well as nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs. Clinically the classical signs of infection are not present, but there is a fetid odor, and the extraction site is devoid of a clot or shows evidence of poor healing with food debris. After irrigation and insertion of a medicated dressing, relief is experienced within minutes. Commercially prepared radiograph detectable dressings containing 20% eugenol are available for use. Dry socket pastes containing eugenol, guaiacol, chlorobutanol, and balsam of peru are also available and can be impregnated onto radiograph detectable filament gauze for use as a dressing. The dressings are usually replaced every day or 2 after irrigation with normal saline. The symptoms dissipate after several days; however, on occasion they may persist longer. Beyond 3 weeks, radiographs should be taken and reviewed, and the patient should be examined clinically to rule out a different cause for the discomfort.

INFECTION

Signs and symptoms manifest within 3 to 4 days. They are usually increased swelling, trismus, and tenderness along with redness, an elevated temperature, general malaise, and many times a purulent exudate.

Infections can occur postoperatively 3 to 4 days to several weeks after surgery. Most of these develop in third molar extraction sites, and the incidence has been reported to be anywhere from 3% to 5%. Infection after dental extractions usually occurs in surgical cases requiring flap elevation and bone removal. Patients who have poor oral hygiene, periodontal disease, and are immunocompromised are more susceptible to postoperative dental infections. Streptococci species of bacteria appear to be the largest group of bacteria causing postoperative oral infections, and studies have shown these infections have an average of four different bacteria with anaerobic outnumbering aerobic species. The most effective treatment continues to be penicillin. However, because of the increased recognition of anaerobic organisms in these infections, metronidazole or clindamycin can be substituted for them. When given prophylactically to patients with debilitating medical conditions or periodontal disease, antibiotics are thought to be of some value. Use of preoperative and postoperative antibiotics is still a controversial topic. This practice may make treatment of subsequent infections more difficult because of resistant strains of bacteria. There are some reports of a bacteremia being associated with the extraction of teeth. This is a rare occurrence. In addition to antibiotic therapy, an incision and drainage should be performed and cultures obtained for sensitivity testing. In severe cases, consultation should be sought with infectious diseases. Infection can be minimized by following good surgical techniques with copious irrigation and adhering to principles of asepsis. Infections following extractions can occur even when the surgeon uses proper surgical techniques. The patient’s local and systemic response to surgery, the virulence of the bacteria on the area of the surgery, and the postoperative compliance of the patient can place the patient at an increased risk for infection.

BISPHOSPHONATE-RELATED OSTEONECROSIS (BRON)

Oral bisphosphonates, such as Fosamax, Actonel, Boniva, Didronel, and Skelid, are being used to treat osteoporosis, osteopenia, Paget’s disease of bone, and osteogenesis imperfecta of childhood. The intravenous bisphosphonates, pamidronate (Aredia), and zoledronic acid (Zometa) are being used in the treatment and management of cancer-related conditions. In 2003 and 2004, oral surgeons published reports of nonhealing exposed bone in the maxillofacial region in patients on intravenous bisphosphonates. Subsequent to these reports, additional case series were published. In 2004, health care professionals were notified by the manufacturer of the complications with IV bisphosphonates, and in 2005 a broader class warning was released that included the oral bisphosphonates. The American Association of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgeons (AAOMS) considers a patient to have BRON if they have all three of the following characteristics:

- 1.

Current or previous treatment with a bisphosphonate

- 2.

Exposed bone in the maxillofacial region that has persisted for more than 8 weeks

- 3.

No history of radiation therapy to the jaws

Currently the estimated cumulative incidence of BRON in patients on IV bisphosphonates, which is based on retrospective studies with limited sample sizes, is from 0.8% to 0.12%. Patients on oral bisphosphonate therapy are at a much lower risk than those patients on IV therapy with the estimated risk following extractions to be 0.09% to 0.34%; however, the risk appears to increase if the duration of therapy exceeds 3 years.

In patients with a diagnosis of BRON, treatment should be to eliminate pain, control infection, and prevent the progression or occurrence of osteonecrosis. Hyperbaric oxygen therapy has not been proven to be effective in treatment of these patients, and they do not respond as predictably to surgical treatments that are used for osteomyelitis and osteoradionecrosis. In BRON, bony sequestra should be removed or recontoured without exposing uninvolved bone. The AAOMS has proposed the staging and treatment strategies listed in Table 12-1 for the treatment of patients with BRON.

| BRONJ * Staging | Treatment Strategies † |

|---|---|

| At risk category No apparent exposed/necrotic bone in patients who have been treated with either oral or IV bisphosphonates |

|

| Stage 1 Exposed/necrotic bone in patients who are asymptomatic and have no evidence of infection |

|

| Stage 2 Exposed/necrotic bone associated with infection as evidenced by pain and erythema in the region of the exposed bone with or without purulent drainage |

|

| Stage 3 Exposed/necrotic bone in patients with pain, infection, and one or more of the following: pathologic fracture, extraoral fistula, or osteolysis extending to the inferior border |

|

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses