The treatment of anterior open bite often requires the use of skeletal anchorage to prevent excessive eruption of the posterior teeth and consequent downward rotation of the mandible. However, this procedure might not always be accomplished. This article reports the successful treatment of an anterior open bite and a posterior crossbite in a young boy, combining traditional techniques and involving high-pull maxillary traction to help growth to correct the skeletal Class II malocclusion without skeletal anchorage. The vertical dentoalveolar contribution of maxillary growth was also favorable to close the bite, whereas cross-elastics corrected the axial inclination of the mandibular posterior teeth, eliminating the inverted posterior crossbite. The open bite was completely closed with edgewise appliances, which also achieved normal overjet, intercuspation, and incisor exposure on smiling. Traditional mechanics for the treatment of open bite and crossbite remain a useful alternative when patients do not accept skeletal anchorage.

An anterior open bite is one of the most difficult malocclusions to treat, and the difficulty increases considerably when it is associated with a posterior crossbite. An anterior open bite can be caused by skeletal vertical disharmony, muscular imbalance, habits, or local alveolar growth deficiency. Posterior crossbites can also have several etiologies, including transverse skeletal imbalance between the maxilla and the mandible, and altered tooth positioning in a buccal-palatal or lingual direction.

The treatments for open bite and crossbite are determined by their etiology and diagnosis. Large skeletal imbalances must be corrected surgically, but tooth and alveolar disharmonies can be corrected by dentoalveolar movement.

Complex malocclusions must be treated by combining treatment concepts and techniques to achieve an effective result. This article describes the diagnosis and treatment of a young patient with a severe anterior open bite and a posterior crossbite.

Diagnosis and etiology

The patient, a 10-year-old boy with no significant medical history, had a symmetrical face with balanced proportions, a pleasant profile, and a passive lip seal. His chief complaint was an anterior open bite. He had reduced exposure of the maxillary incisors at rest (−2 mm) and during smiling (6 mm) ( Fig 1 ). Intraorally, he exhibited a Class I molar-canine permanent dentition with a 5-mm overjet, an open bite of 6 mm at the central incisors extending laterally to the premolars on both sides, and also a posterior crossbite on the right side. He was a mouth breather and had abnormal tongue posture during speech and a history of thumb sucking.

The arch-length discrepancy was positive (8 mm in the maxilla, 10.5 mm in the mandible). The distances between the mesiobuccal cusp tips of the right and left first permanent molars were 41 mm in the mandibular arch and 55 mm in the maxillary arch. The distances between the cusp tips of the right and left canines were 29 mm in the mandibular arch and 36 mm in the maxillary arch. Ward et al reported average values for mandibular and maxillary intermolar distances of 44.20 and 50.14 mm, respectively, and for mandibular and maxillary intercanine distances of 25.18 and 33.06 mm, respectively. All measurements for arch-width dimensions were above the average expected values except for the mandibular molars, which were below normal values. Analysis of the mandibular arch showed that the right side was more constricted, suggesting an asymmetric constriction of the mandibular arch ( Fig 2 ).

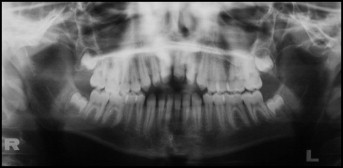

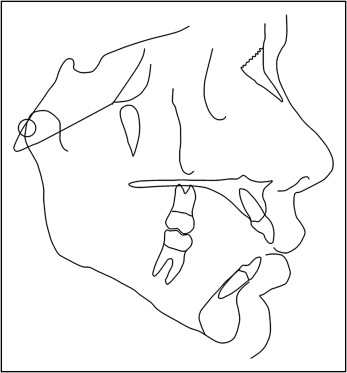

The panoramic radiograph showed normal root anatomy and no caries ( Fig 3 ). Cephalometric analysis showed skeletal horizontal disharmony as evidenced by the ANB (6°) and convexity (10°) angles ( Fig 4 , Table ). The vertical relationship was accentuated as seen by GoGn.SN (34°), FMA (29°), and y-axis (64°). The maxillary and mandibular incisors were protruded; the maxillary incisors to the NA angle was 31°, and the maxillary incisors to NA distance was 5 mm; the mandibular incisors to the NB angle was 39°, and the mandibular incisors to NB distance was 8.5 mm; IMPA was 107°. The hand-wrist radiograph showed a bone age of 10 years 5 months, indicating that a significant amount of growth was still expected.

| Measurement | Normal | Pretreatment | Posttreatment | Difference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Skeletal pattern | ||||

| SNA (°) | 82 | 84 | 84 | 0 |

| SNB (°) | 80 | 78 | 82 | 4 |

| ANB (°) | 2 | 6 | 2 | −4 |

| Facial convexity (°) | 0 | 10 | 2 | −8 |

| Y-axis (°) | 59 | 64 | 62 | −2 |

| Facial angle (°) | 87 | 85 | 87 | 2 |

| SN.GoGn (°) | 32 | 34 | 30 | −4 |

| AO-BO (mm) | 0 | 8.5 | 3.5 | −5 |

| FMA (°) | 25 | 29 | 28 | −1 |

| Dental pattern | ||||

| IMPA (°) | 90 | 107 | 90 | −17 |

| 1.NA (°) | 22 | 31 | 22 | −9 |

| 1-NA (mm) | 4 | 5 | 6 | 1 |

| 1.NB (°) | 25 | 39 | 23 | −16 |

| 1-NB (mm) | 4 | 8.5 | 6 | −1.5 |

| 1.1 (°) | 130 | 104 | 133 | 29 |

| Profile | ||||

| Upper lip to S-line (mm) | 0 | 1.5 | −1.5 | −3 |

| Lower lip to S-line (mm) | 0 | 0.5 | −2.5 | −3 |

Treatment objectives

The primary objectives in the treatment of this patient were to (1) correct the tongue habit, (2) correct the posterior crossbite at the right side to achieve proper intercuspation, (3) vertically control the maxillary posterior teeth to prevent mandibular plane opening, (4) correct the skeletal Class II malrelationship, and (5) erupt the maxillary incisors to close the bite and increase tooth exposure.

Treatment objectives

The primary objectives in the treatment of this patient were to (1) correct the tongue habit, (2) correct the posterior crossbite at the right side to achieve proper intercuspation, (3) vertically control the maxillary posterior teeth to prevent mandibular plane opening, (4) correct the skeletal Class II malrelationship, and (5) erupt the maxillary incisors to close the bite and increase tooth exposure.

Treatment alternatives

Several treatment modalities are proposed in the literature for nonsurgical anterior open-bite treatment, including high-pull headgear, vertical-pull chincups, multiloop edgewise archwires, tongue cribs, and posterior bite devices (active and passive). All of these require long treatment times and patient compliance. Another option was skeletal anchorage with miniplates or microscrews to intrude the posterior teeth. Skeletal anchorage eliminates the need of patient compliance; yet not all patients and parents agree to a surgical procedure, even if it is relatively minor, such as placement of miniplates or microscrews.

The asymmetry of the mandibular arch was shown by the right constricted posterior arch contributing to the crossbite. So this asymmetry had to be corrected. The options were (1) asymmetric mechanics with fixed appliances, (2) cantilever arms to expand the mandibular right posterior arch, (3) microscrews at the buccal-alveolar region between the posterior tooth roots to anchor the expansion of this segment, and (4) cross-elastics anchored in a maxillary splint.

Treatment plan

Traditional orthodontic mechanics such as high-pull headgear, cross-elastics, and fixed appliances can be successfully used in many patients, when proper diagnoses and treatment planning are made, and this was chosen by the parents and our patient as the first treatment option to obtain the treatment objectives.

Skeletal anchorage to intrude the maxillary posterior teeth and expand the mandibular right posterior teeth was considered the second treatment alternative to be used as an option only if cooperation was not satisfactory.

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses