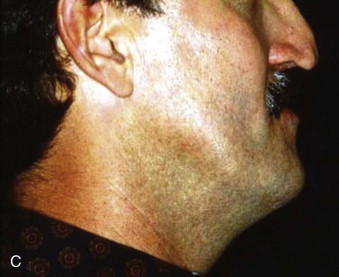

Rehabilitation of the cleft lip and palate patient populations requires a multidisciplinary team of craniofacial surgeons, oral and maxillofacial surgeons, orthodontists, pediatric dentists, restorative dentists, and speech and swallowing pathologists. Treatment of these patients during the growing years requires an understanding of craniofacial growth and its effect on the timing of implant placement. Although not documented as intensively in the literature, there are the psychological and functional deficiencies associated with this patient population. In years past, many of these patients experienced problems with shyness, depression, social isolation, fighting, and impulsive behavior. The functional deficits of a decreased vertical dimension of occlusion, decreased facial support, temporomandibular joint symptoms, lack of functional occlusion, altered speech, poor esthetics, lack of a normal smile, and altered anatomy in the lower third of the face contributed to a feeling of being different from other children. With the recent advances in both medical and dental technologies, this patient population can now be rehabilitated to a near normal appearance ( Fig. 89-1 ).

Treatment and Restorative Goals

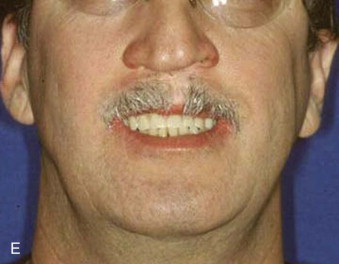

Prosthodontics originally played a much greater role with this patient population ( Fig. 89-2 ). For example, speech bulb prostheses ( Fig. 89-3, A ), obturators, and palatal lift prostheses ( Fig. 89-3, B ) were used in the past as definitive treatment. Now, they are rarely used and, if used at all, only as an interim measure. For the growing cleft palate child, most velopharyngeal discrepancies are managed surgically with a palatal push-back and closure procedure at 9 to 18 months, followed by a superiorly placed pharyngeal flap at 3 to 7 years. Today, a prosthesis is made only for patients with failed attempts following pharyngeal surgery. The prosthesis is used to correct the resulting hypernasality and inadequate speech. In addition, a prosthesis may also be used in those situations in which the cleft is confined to the secondary palate. In cases of velopharyngeal insufficiency in which the surgically repaired soft palate is too short and does not make contact with the pharyngeal walls during function, a prosthesis allows proper nasal airflow, resulting in normal speech and prevention of nasal regurgitation while eating. Its purpose is to seal the nasal cavity from the oropharynx during bodily functions of eating and speaking. In cases of velopharyngeal incompetency in which the surgically repaired soft palate is of adequate length but of inadequate mobility to elevate to achieve velopharyngeal closure, the palatal lift prosthesis elevates the soft palate, contributing to normal speech. For this prosthesis to be most effective and to prevent the opposing downward muscle force of the soft palate, retention is most important. This prosthesis requires clasping multiple teeth for adequate retention. In those situations in which surgical repair was unsuccessful or an oronasal fistula is present, an obturator prosthesis may be necessary as an interim measure. One significant advancement in the care of the infant cleft lip and palate patient has been nasoalveolar molding. This prosthesis is used prior to cleft lip repair to bring in the alveolar arches and to elongate the columella ( Fig. 89-4 ).

Currently, the greatest prosthetic issue facing the growing cleft palate patient is treatment for the edentulous alveolar cleft and missing teeth. It is important to remember that jaw growth and dentoalveolar development do not follow normal patterns of growth. The prosthetic needs of the growing cleft child during the primary dentition state are minimal. Usually, jaw relationships, occlusion, and individual teeth remain relatively stable. In cases of severe tooth decay and tooth loss, the occlusion and jaw relationship may vary during growth. On the other hand, with the mixed dentition stage, there is a discrepancy between the maxillary and mandibular arches with respect to size. Definitive prosthodontic care is usually one of the last treatments needed and is recommended after the completion of craniofacial growth, usually after 18 years of age.

Treatment Techniques

Hypodontia

Hypodontia has been reported to occur approximately 10 times more frequently on the cleft side in this patient population. Ranta found a positive association between hypodontia and cleft severity, with the incidence of hypodontia increasing strongly with the cleft’s severity. Bohn reported a prevalence of tooth agenesis of 46% in the cleft area, whereas Slayton et al reported an incidence of 48% for missing lateral incisors for this patient population. Shapira et al found a 77% incidence of hypodontia in nonsyndromic cleft children. The tooth most commonly missing is the permanent maxillary lateral incisor (74% incidence) followed by the maxillary and mandibular second premolars. Prosthetic treatment of implant prosthetics and fixed prosthetics are more commonly used to address these functional deficits.

Edentulous Cleft Site

Although the lip and nose are satisfactorily repaired, inadequate bony contour, maxillary retrognathism, and hypodontia contribute to the severity of the facial deformity. Hence, addressing the closure of the edentulous cleft site with bone grafting is critically important. The objectives of bone grafting include providing bony support to the adjacent teeth, facilitating prosthetic restoration, providing bony matrix for tooth eruption into the cleft site, stabilizing the segments, elevating the alar base, eliminating the oronasal fistula, and providing adequate bone volume for implant placement. Bone grafting is necessary in 30% to 40% of cleft palate patients. It has been reported that the best results are achieved if the graft was done between the ages of 9 to 11 before the eruption of the canines. Grafting allows the cleft to be restored either with orthodontics, conventional prosthodontics of either a removable partial denture or a fixed prosthesis, or implant prosthesis.

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses