The comprehensive treatment of cleft lip and palate deformities requires thoughtful consideration of the anatomic complexities of the deformity and the delicate balance between intervention and growth. Comprehensive and coordinated care from infancy through adolescence is essential to achieve the best outcome, and surgeons with formal training and experience in all the phases of care must be actively involved in the planning and treatment. Specific goals of surgical care for children born with cleft lip and palate include the following:

- •

Normalized esthetic appearance of the lip and nose

- •

Intact primary and secondary palate

- •

Normal speech, language, and hearing

- •

Nasal airway patency

- •

Class I occlusion with normal masticatory function

- •

Good dental and periodontal health

- •

Normal psychosocial development

Successful management of the child born with a cleft lip and palate requires coordinated care provided by a number of different specialties, including oral and maxillofacial surgery, otolaryngology, plastic surgery, genetics and dysmorphology, speech-language pathology, orthodontics, pediatric dentistry, and prosthodontics. In most cases, care of patients with congenital clefts has become a subspecialty area of clinical practice within these different professions. In addition to the primary cleft repairs in infancy, treatment plans routinely involve multiple treatment interventions to achieve the above goals staged throughout childhood. Because care is provided over the entire course of the child’s development, long-term follow-up is essential under the care of these different health care providers.

The formation of interdisciplinary cleft palate teams has served two key objectives of successful cleft care: (1) coordinated care provided by the necessary disciplines and (2) continuity of care with close-interval follow-up of the patient throughout periods of active growth and ongoing stages of reconstruction. The best outcomes are achieved when the team’s care is centered on the patient, family, and community rather than a particular surgeon, specialty, or hospital. Healthy team dynamics and optimal patient care are achieved when all members are active participants, when team protocols and referral patterns are equitable, and when the needs of the child are placed above the needs of the team or individual members.

The surgical reconstruction of clefts requires that the surgeon undertaking this important work maintain a cognitive understanding of the complex malformation itself, the varied operative techniques used, facial growth considerations, and the psychosocial health of the patient and family. This chapter presents the overall staged reconstructive approach for repair of cleft lip and palate from infancy through the time of skeletal maturity, as well as a discussion of the surgical procedures involved in cleft lip and palate repair.

Genetics and Etiology

Clefts of the upper lip and palate are the most common major congenital craniofacial abnormality and are present in approximately 1 in 600 live births. Although inheritance may play a role, cleft lip and palate is often not considered a single-gene disease. Instead, clefts are thought to be of a multifactorial etiology with a number of potential contributing factors. These factors may include chemical exposures, radiation, maternal hypoxia, teratogenic drugs, nutritional deficiencies, physical obstruction, and genetic influences. One prevailing theory relates the process of clefting as a point when multiple factors come together to raise the individual above a threshold, at which time the mechanism of fusion fails. Multiple genes recently have been implicated in the etiology of clefting. Some of these genes include the MSX , LHX , goosecoid , and DLX genes. Additional disturbances in growth factors or their receptors that may be involved in the failure of fusion include fibroblast growth factor, transforming growth factor, platelet-derived growth factor, and epidermal growth factor.

Clefts of the lip occur more commonly in males than in females. In addition, left-sided cleft lips are more common than right-sided cleft lips, and unilateral cleft lips are more common than bilateral cleft lips. Bilateral clefts of the lip are most often associated with clefting of both the primary and secondary palates. Cleft palate alone is seen in approximately 1 in 2000 live births, an incidence similar in all racial groups. Significant differences in the prevalence of clefts exist when specific populations are examined.

In the majority of cases, unilateral cleft lip and palate is an isolated nonsyndromic birth defect not associated with any other major anomalies. By comparison, a much greater proportion of patients with an isolated cleft palate have an associated syndrome or sequence. Some of the more common syndromes seen in this group include Stickler, van der Woude, and DiGeorge syndromes. Early diagnosis is important because functional issues may arise early in life and go unnoticed. For example, patients with an isolated cleft palate should be evaluated early by an experienced pediatric ophthalmologist to evaluate the possibility of Stickler syndrome. Patients with Stickler syndrome may have ocular abnormalities that lead to retinal detachment. In an otherwise healthy-appearing child, these findings may be difficult to diagnose, so early visual loss may go unnoticed. In many cases, long-term genetic follow-up is necessary to make a definitive diagnosis and provide genetic counseling.

Classification

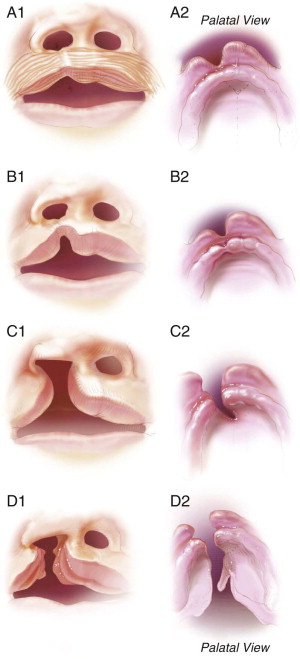

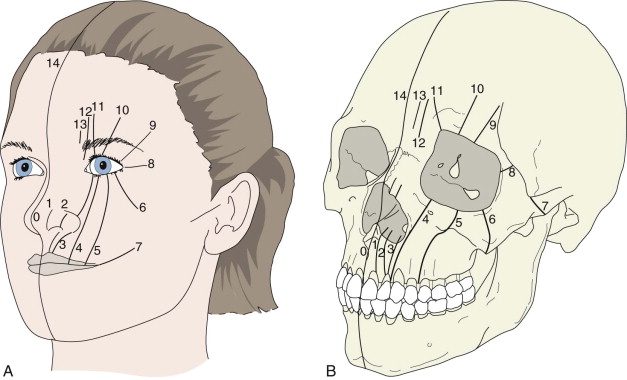

The typical classification system used clinically to describe standard clefts of the lip and palate is based on careful anatomic description. Clefts can be unilateral or bilateral; microform, incomplete, or complete; and may involve the lip, nose, primary palate, and/or secondary palates ( Figs. 85-1 and 85-2 ). The presentation of clefts is extremely variable, and the individual repairs are custom-tailored to achieve the best symmetry and balance. More severe facial clefting is most commonly described by using Paul Tessier’s orbitocentric system of numbering ( Fig. 85-3 ). Other systems are based on embryologic fusion planes, but are these are cumbersome to use in routine clinical practice.

Prenatal Counseling

Recent advances in imaging have revolutionized prenatal care and maternal-fetal medicine. Currently ultrasound images of clefts of the lip can be visualized at about 16 weeks. Diagnostic images of the palate are more difficult to acquire, making the correct prenatal diagnosis of a cleft palate less predictable. Anterior palatal structures may be visualized using sagittal and coronal views, but this currently requires the latest technology and a skilled ultrasonographer with experience performing this type of study.

Classification

The typical classification system used clinically to describe standard clefts of the lip and palate is based on careful anatomic description. Clefts can be unilateral or bilateral; microform, incomplete, or complete; and may involve the lip, nose, primary palate, and/or secondary palates ( Figs. 85-1 and 85-2 ). The presentation of clefts is extremely variable, and the individual repairs are custom-tailored to achieve the best symmetry and balance. More severe facial clefting is most commonly described by using Paul Tessier’s orbitocentric system of numbering ( Fig. 85-3 ). Other systems are based on embryologic fusion planes, but are these are cumbersome to use in routine clinical practice.

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses