This case report describes a novel method of combining lingual appliances and lingual arches to control horizontal problems. The patient, who was 25 years of age at her first visit to our hospital with a chief complaint of crooked anterior teeth, was diagnosed with skeletal Class II and Angle Class II malocclusion with anterior deep bite, lateral open bite, premolar crossbite, and severe crowding in both arches. She was treated with premolar extractions and temporary anchorage devices. Conventionally, it is ideal to use labial brackets simultaneously with appliances, such as a lingual arch, a quad-helix, or a rapid expansion appliance, in patients with complex problems requiring horizontal, anteroposterior, and vertical control; however, this patient strongly requested orthodontic treatment with lingual appliances. A limitation of lingual appliances is that they cannot be used with other conventional appliances. In this report, we present the successful orthodontic treatment of a complex problem using modified lingual appliances that enabled combined use of a conventional lingual arch.

Lingual appliances are often used to correct malocclusions in adult patients who have esthetic concerns. Nevertheless, clinicians face some problems when working with lingual appliances, such as limited visibility during adjustment of the appliances, short distances between neighboring brackets, irregular arch forms, and complicated attaching and detaching processes. However, lingual appliances have become more convenient for orthodontists because of the introduction of self-ligating brackets, the straight-wire technique, customized brackets, and wire-bending robots. Temporary skeletal anchorage devices have also played a part in expanding the applications of lingual appliances, particularly in patients with Angle Class II or Class III malocclusion. Temporary skeletal anchorage devices make it easier to perform anterior tooth retraction and achieve anchorage control to correct molar relationships.

These technologic advancements have solved most of the problems associated with lingual appliances. However, one remaining problem contributes to the unsuitability of such lingual appliances in difficult cases, especially those involving transverse complications: lingual appliances cannot be used with a lingual arch appliance, a quad-helix appliance, or fixed rapid expansion appliances. The use of these appliances is desirable when treating complex problems.

In this report, we describe the treatment of an adult with a Class II malocclusion and complex problems, including a second premolar crossbite resulting from a narrowed maxillary arch. The patient did not wish to undergo orthognathic surgical procedures, instead requesting orthodontic treatment with lingual appliances for esthetic reasons. Although the use of conventional lingual appliances and methods appeared difficult because of the patient’s severe vertical and horizontal problems, we modified the appliance design and treatment technique to satisfy her request.

The most notable point in this case was the modified design of the lingual appliances, which enabled the combined use of lingual appliances and a lingual arch, successfully addressing the horizontal problems. We believe that this approach will broaden future orthodontic treatment choices.

Diagnosis and etiology

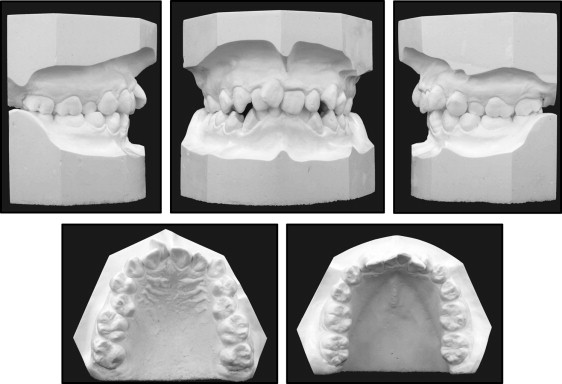

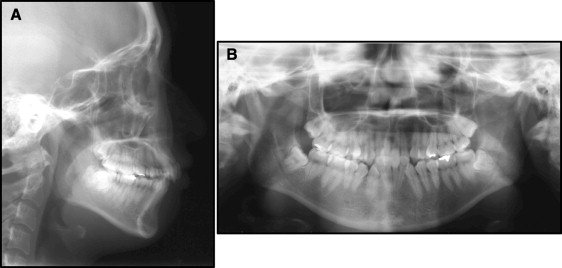

A woman, 25 years 4 months of age, consulted the outpatient clinic of Okayama University Hospital with a chief complaint of crooked teeth. She strongly desired nonsurgical treatment with an invisible appliance. Her convex profile was due to a retrognathic mandible with upper lip protrusion. Circumoral muscle strain was observed upon mouth closure. Anterior incisor deepbites with an excessive overjet of 8 mm and a deep overbite of 7 mm were observed. A severe curve of Spee was noted in the mandibular occlusal plane (4 mm). Severe crowding was present in both arches (arch length discrepancies: maxilla, −8.6 mm; mandible, −10.9 mm). The maxillary right central incisor had a gingival recession on the distal side caused by labial malposition and mesial rotation. The amount of attachment loss of the maxillary right central incisor was 2.0 mm in contrast to the left side. Both maxillary second premolars exhibited crossbites because of palatally dislocated maxillary second premolars. The mandibular incisors were inclined lingually, and both canines were dislocated labially. The molar relationship was Angle Class II on both sides. The maxillary dental midline was deviated 3 mm toward the right of the facial midline, although the mandibular dental midline was not deviated from the facial midline. The dental radiographs showed normal root lengths with no horizontal or vertical bone loss ( Figs 1-3 ).

In comparison with the Japanese norm, a skeletal Class II relationship (ANB angle, 5.8°) with mandibular retrusion (SNB angle, 74.8°) was observed ( Table ). The body length of the mandible was small (Ar-Me, 97.7 mm). The mandibular plane angle was normal (Mp-SN, 40.9°). The maxillary incisors were lingually inclined (U1-SN, 91.0°), and the height of the incisors was normal (U1/PP, 30.2 mm). The mandibular incisors were lingually inclined (L1-Mp, 86.9°), and the height from the mandibular plane was excessive (L1/Mp, 49.4 mm). The occlusal plane angle was average (18.2°).

| Mean | SD | Pretreatment | Posttreatment | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Angular analysis (°) | ||||

| SNA | 80.8 | 3.6 | 80.5 | 80.1 |

| SNB | 77.9 | 4.5 | 74.8 | 74.6 |

| ANB | 2.8 | 2.4 | 5.8 | 5.6 |

| Mp-SN | 37.1 | 4.6 | 40.9 | 41.6 |

| Gonial angle | 122.1 | 5.3 | 119.7 | 122.4 |

| U1-SN | 105.9 | 8.8 | 91.0 | 87.6 |

| L1-Mp | 93.4 | 6.8 | 86.9 | 91.4 |

| IIA | 123.6 | 10.6 | 141.2 | 139.4 |

| Occlusal plane | 16.9 | 4.4 | 18.2 | 22.3 |

| Linear analysis (mm) | ||||

| PTM-A/PP | 47.9 | 2.8 | 46.7 | 46.7 |

| PTM-ANS/PP | 52.1 | 3.0 | 50.9 | 51.1 |

| Go-Me | 71.4 | 4.1 | 66.3 | 66.4 |

| Ar-Go | 47.3 | 3.3 | 43.0 | 40.8 |

| Ar-Me | 106.6 | 5.7 | 97.7 | 96.7 |

| U6/PP | 24.6 | 2.0 | 22.7 | 22.4 |

| U1/PP | 31.0 | 2.3 | 30.2 | 30.1 |

| L6/Mp | 32.9 | 2.5 | 35.2 | 36.0 |

| L1/Mp | 44.2 | 2.7 | 49.4 | 46.3 |

| Overjet | 3.1 | 1.07 | 7.0 | 2.6 |

| Overbite | 3.3 | 1.89 | 6.7 | 2.4 |

Treatment objectives

We diagnosed the patient with an Angle Class II malocclusion, a skeletal Class II jaw-base relationship, anterior deep bite, lateral open bite, premolar crossbite, severe maxillary and mandibular crowding, and midline deviation. The treatment objectives were to correct the severe crowding, midline deviation, and lateral open bite; establish an ideal incisor relationship; and achieve an acceptable occlusion with a favorable functional Class I occlusion. We also planned to perform genioplasty to protrude the patient’s chin, as it would be difficult to correct the convex profile using only orthodontic treatment, owing to the skeletal problems and severe dental discrepancy. Since the mandibular dental discrepancy was too severe to control the molar relationships, we planned to place temporary skeletal anchorage devices in the retromolar areas to provide skeletal anchorage to correct the molar relationships. Additionally, extractions of 4 premolars and 4 third molars were required to correct the severe crowding.

Furthermore, the patient preferred to undergo lingual bracket treatment for esthetic reasons. However, it was difficult to use lingual brackets because she required highly technical tooth control in the horizontal, anteroposterior, and vertical directions. Ultimately, we decided to avoid the use of labial brackets on the maxillary incisors only.

Treatment objectives

We diagnosed the patient with an Angle Class II malocclusion, a skeletal Class II jaw-base relationship, anterior deep bite, lateral open bite, premolar crossbite, severe maxillary and mandibular crowding, and midline deviation. The treatment objectives were to correct the severe crowding, midline deviation, and lateral open bite; establish an ideal incisor relationship; and achieve an acceptable occlusion with a favorable functional Class I occlusion. We also planned to perform genioplasty to protrude the patient’s chin, as it would be difficult to correct the convex profile using only orthodontic treatment, owing to the skeletal problems and severe dental discrepancy. Since the mandibular dental discrepancy was too severe to control the molar relationships, we planned to place temporary skeletal anchorage devices in the retromolar areas to provide skeletal anchorage to correct the molar relationships. Additionally, extractions of 4 premolars and 4 third molars were required to correct the severe crowding.

Furthermore, the patient preferred to undergo lingual bracket treatment for esthetic reasons. However, it was difficult to use lingual brackets because she required highly technical tooth control in the horizontal, anteroposterior, and vertical directions. Ultimately, we decided to avoid the use of labial brackets on the maxillary incisors only.

Treatment alternatives

Two major procedures (with and without orthognathic surgery) were explored to achieve an ideal Class I occlusion and a good profile. Although mandibular and chin advancements with orthognathic surgery are considered an effective treatment method, the patient did not want to undergo surgery for social and physiologic reasons and the need for prolonged hospitalization. Furthermore, the physical disadvantages of a surgical invasion caused her to decline this option, in addition to the fact that she was not dissatisfied with her facial profile. Therefore, we chose orthodontic treatment with premolar extraction.

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses