Fig. 3.1

Drainage of pus from a periapical abscess may be obtained through the root canal or by a surgical incision

To Get Access to and Treat a Previously Untreated Root Canal

A Continuously “Weeping” Root Canal

A root canal treatment can usually be completed in one or two visits. However, there are situations in which a root canal treatment is difficult to terminate and close because the root canal system or surrounding tissues continue to give clinical signs of ongoing severe inflammation. Two different situations can easily be recognized.

The first is when the root canal despite proper root canal treatment continues to fill up with serous exudate, pus or blood. The clinician might have postponed the root filling procedure several weeks or even months using an intracanal dressing with calcium hydroxide. Despite these attempts, when opening the tooth, it is still impossible to achieve a dry root canal. Under such circumstances, there is an indication to get surgical access to the periradicular tissues before root canal obturation. Two different strategies may be considered. If the procedure is not foreseen to be too complicated or time-consuming, the surgical access and root canal filling can be accomplished in one treatment session. The first step is to expose the inflamed periapical region by surgical means. The granulation tissue or radicular cyst present in the bony crypt is removed, and before suturing the flap, the root canal is exposed preferably under normal aseptical considerations (rubber dam, sterile instruments). The surgeon covers the wound with the flap without suturing. The root canal is cautiously irrigated with a low concentration of sodium hypochlorite and possibly EDTA. Immediately after finishing the irrigation the canal is dried and root filled with gutta-percha and sealer. Overfill of the canal is of minor concern since any excess of root filling material easily can be removed from the apical area during a final cleaning of the apical area before suturing the flap. As an alternative, the root canal may be filled with gutta-percha with a retrograde root filling technique (see under Situations of unfavourable access through the crown). One other option is that after removal of the periapical pathology, the root end is filled with an MTA plug and the root canal is left with a temporary dressing with calcium hydroxide. The permanent root filling procedure is postponed until a later visit (preferably when the soft tissues have healed and sutures have been removed, usually 1–6 weeks after surgery).

In other situations clinical signs of apical periodontitis, i.e. fistulae, swelling or pain, do not alleviate or cure despite a diligent and proper root canal treatment. The root canal is dry and without signs of remaining infection inside the accessible parts of the root canal. In such a situation, it is considered an option to finalize orthograde root canal treatment and plan for an additional surgical access.

Situations of Unfavourable Access Through the Crown

Orthograde access to the root canal system in abutment teeth or in teeth with significant root canal calcification may pose risks for complications. An extensive drilling to identify and negotiate the canal system through the crown may lead to extensive loss of tooth substance and undermine the abutment and consequently cause prosthodontic failure [44, 47]. The use of the operating microscope obviously makes these procedures more predictable and less daring [37]. But still, a surgical approach as a primary endodontic treatment on specific indications may mean a less invasive procedure and fewer risks of complications [35, 56].

After a conventional method to endodontic surgical intervention, the canal is enlarged and cleaned with Hedstroem files held in a haemostat or with ultrasonic preparation. The root canal is cautiously irrigated during the preparation with a low concentration of sodium hypochlorite and EDTA. Following instrumentation, the canal is dried with paper points and filled with sealer, thermoplasticized gutta-percha and a matched single cone of gutta-percha (Fig. 3.2). In cases where only a limited part of the canal can be explored, alternative materials such as MTA (mineral trioxide aggregate) can be considered for the retrograde filling (Fig. 3.3). Surgical root canal treatment may primarily be considered for incisors and canines and in some two-rooted premolars. However, retrograde access varies between patients and in different parts of the jaws. The feasibility of retrograde root canal treatment should therefore carefully be investigated preoperatively, both clinically and radiographically.

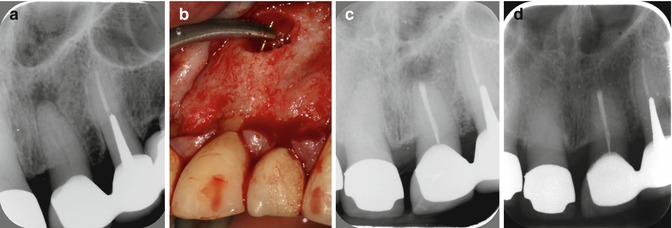

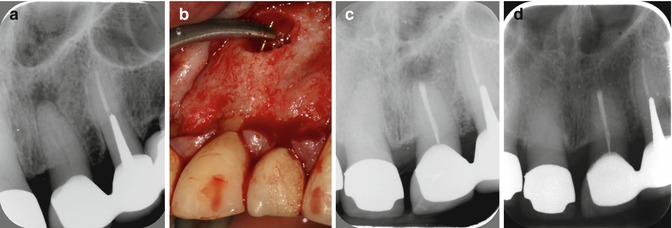

Fig. 3.2

Left central incisor with apical periodontitis and abutment tooth in a bridge. (a) Preoperative radiograph, (b) the root canal was instrumented with hand files in a haemostat, (c) postoperative radiograph with retrograde root canal filling with sealer and warm gutta-percha technique, (d) 1-year postoperative radiograph

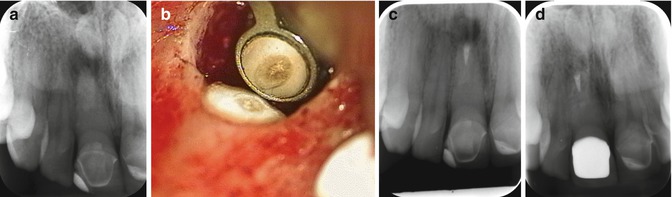

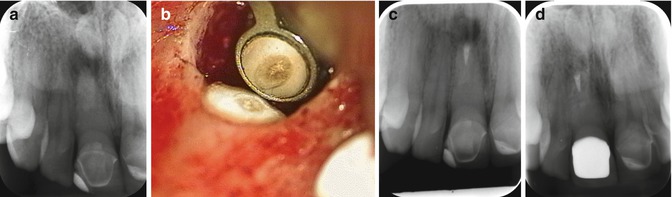

Fig. 3.3

Successful outcome of a surgical root canal treatment of a right central incisor with a root canal obliteration and apical periodontitis after trauma. (a) Preoperative radiograph, (b) the tip of the root-resected central incisor with an extensive root canal calcification, (c) postoperative radiograph with a limited retrograde filling with MTA due to canal obliteration, (d) healing after 1 year

In case reports, it has been shown that surgical root canal therapy has good potential to result in clinically and radiographically healthy periapical tissues [35]. Yet, there are no studies published which systematically compared the outcome of surgical root canal treatment with a conventional treatment protocol. Such studies are now being carried out [34].

To Get Access to and Treat a Previously Root-Filled Root Canal

A root canal treatment can be considered closed as the tooth receives a permanent root filling. Postoperative discomfort sometimes occurs, but after a short period most teeth become asymptomatic. Normally the tooth is restored with a filling or crown as soon as possible.

Successful Root Canal Treatments

For a root canal treatment to be considered completely successful in the long term, it requires not only that the tooth is functional and asymptomatic. When the root-filled tooth is examined clinically and radiographically, it should also be free of clinical signs of inflammation showing normal surrounding bony structures. If radiographic signs of inflammation persist, although presently asymptomatic, it is likely that the root-filled tooth is containing bacteria or other microorganisms. Pain and swelling may thus reoccur. The tooth may also be a source of infectious agents spread both locally and to the body’s organs.

Failed Root Canal Treatments

When root-filled teeth cause pain and swelling, it is usually a sign of infection. Similarly, chronic clinical findings at the root-filled tooth in the form of redness, tenderness and fistulas are signs of the presence of microbiota in the root-filled tooth.

In these situations it is usually relatively straightforward to diagnose a persistent, recurrent or arising apical periodontitis. The treatment result is classified as a “failure”. There is an obvious indication for a new treatment intervention, retreatment or extraction of the tooth (or sometimes only a root).

However, a common situation is that the root-filled tooth is both subjective and clinically asymptomatic, but an X-ray reveals that bone destruction has emerged or that the original bone destruction remains. In cases where no bony destruction was present when the root canal treatment was completed, and in particular in cases of vital pulp therapy, it can be reasonably assumed that an infection has set in the root canal system. For teeth that exhibited clear bone destruction at treatment start, there must be some time allowed for healing and bone formation to occur. One difficulty is to determine how long is the time required for such a healing process, both in general and in the particular case. The majority of root canal-treated teeth with bone destruction in the initial situation show signs of healing within 1 year [57]. In individual cases, however, the healing process can last for a long time [11, 72]. Molven et al. [46] has reported isolated cases requiring more than 25 years to completely heal. The finding that there are no absolute time limits as to when healing may occur can also be deduced from epidemiological studies [38].

Controversies of “Success” and “Failures” of Root Canal Treatment

Besides the time aspect, there is also a problem of determining what should be considered as a sufficient healing of bone destruction to constitute successful endodontic treatment. And as a consequence also, what establishes a “failure” and hence an indication for retreatment is far from unambiguous. According to the system launched by Strindberg [72], the only satisfactory posttreatment situation, after a predetermined healing period, combines a symptom-free patient with a normal periradicular situation. Only cases fulfilling these criteria were classified as “successes” and all others as “failures”. In academic environments and in clinical research, this strict criteria set by Strindberg in 1956 has had a strong position.

However, the diagnosis of periapical tissues based on intra oral radiographs has repeatedly unmasked considerable inter- and intraobserver variation [63].

As an alternative, the periapical index (PAI) scoring system was presented by Orstavik et al. [58]. The PAI provides an ordinal scale of five scores ranging from “healthy” to “severe periodontitis with exacerbating features” and is based on reference radiographs with verified histological diagnoses originally published by Brynolf [10]. In this doctoral dissertation, the radiographic appearance of periapical tissue was compared with biopsies. The results indicated that using radiographs, it was possible to differentiate between normal states and inflammation of varying severity and that the likelihood of a correct diagnosis improved if more than one radiograph were taken. However, the studies were based on a limited patient spectrum, and the biopsy material was restricted to the upper anterior teeth. Among the researchers, the PAI is well established and it has been used in both clinical trials and epidemiological surveys. Researchers often transpose the PAI scoring system to the terms of Strindberg system by dichotomizing score 1 and 2 to “success” and score 3, 4 and 5 into “failure”. However, the “cut-off” line is arbitrary and comparisons between the two systems for evaluation are lacking in the literature. The Strindberg system, with its originally dichotomizing structure into “success” and “failure”, has achieved status as a normative guide to clinical action. Consequently, when a new or persistent periapical lesion is diagnosed in an endodontically treated tooth, failure is at hand and retreatment (or extraction) is indicated.

However, as early as 1966, Bender et al. [7] suggested that an arrested size of the bone destruction in combination with an asymptomatic patient should be sufficiently conditions for classifying a root canal treatment as endodontic success. More recently, Friedman and Mor [23] as well as Wu et al. [81] have suggested similar less strict classifications of the outcome of root canal treatment.

Uncertainties regarding the validity of the radiographic examination [8, 13, 55] are also of concern. For obvious practical and ethical reasons, only a limited number of studies have compared the histological diagnosis in root-filled teeth with and without radiographic signs of pathology [3, 10, 28]. In these studies, false-positive findings (i.e. radiographic findings indicate apical periodontitis while histological examination does not give evidence for inflammatory lesions) are rare. False-negative findings (i.e. radiographic findings indicate no apical periodontitis while histological examination does give evidence for inflammatory lesions) vary in the different studies. However, it is well known that bone destruction and consequently apical periodontitis may be present without radiographic signs visible in intraoral radiographs (Bender and Seltzer 1961, reprinted in Journal of Endodontics [5, 6]).

The advent of cone beam computed tomography (CBCT) has attracted much attention in endodontics in recent years. In vitro studies on skeletal material indicate that the method has higher sensitivity and specificity than intraoral periapical radiography. The higher sensitivity is confirmed in clinical studies. The major disadvantages of CBCT are greater cost and a potentially higher radiation dose, depending on the size of the radiation field being used. However, one benefit of the CBCT method is that it is relatively easy to apply. Moreover it provides a three-dimensional image of the area of interest, an advantage when assessing the condition of multirooted teeth. And the uncertainty of assessing results of endodontic treatment in follow-up using conventional intraoral radiographic technique has been pointed out [80]. Consequently, it has been suggested that CBCT should be used in clinical studies, because of the risk that conventional radiography underestimates the number of unsuccessful endodontic treatments. However, it may be important not to jump into conclusions since long-term studies are required to investigate if healing of periapical bone destruction may take longer than previously assumed. For example, at 1-year postendodontic treatment follow-up, CBCT can show persisting bone destruction, while a conventional intraoral radiograph shows healing [14]. This question is highly relevant and should be addressed in future research.

Prevalence of Failed Root Canal Treatments

The presence of subjective or clinical signs of failed root canal treatment is only occasionally reported in published follow-ups. The results are measured thus exclusively through an analysis of X-rays [52]. In epidemiological cross-sectional studies of periapical disease, the frequency of periapical radiolucencies in root-filled teeth varies between 25 and 50 % [18]. When periapical bone destruction is considered as a treatment failure and an indication for a new intervention, the potential retreatment cases are numerous. An estimate of the prevalence of endodontic failure cases resulted in 1.7–3.6 million in Sweden, 3.3–7.1 million in Australia and 54–117 million in the USA [21]. The high frequency of root-filled teeth with periapical bone destructions seems to persist despite that the technical quality of root fillings has improved over time [24, 59].

Consequences of Apical Periodontitis in Root-Filled Teeth

Little is known about the frequency of persistent pain in root-filled teeth. From the available data in follow-up studies from university or specialist clinics, in a systematic review, the frequency of persistent pain >6 months after endodontic procedures was estimated to be 5 % [51]. The risks of persistent asymptomatic apical periodontitis in root-filled teeth is not yet very well known. A large majority of lesions remain asymptomatic with only small alteration in radiographically detectable size. It is known that this often silent inflammatory process sometimes turns acute with development of local abscesses that have the potential for life-threatening spreading to other parts of the body. However, the incidence and severity of exacerbation of apical periodontitis at root-filled teeth have met only scarce attention from researchers. Based on epidemiological data Eriksen [18] has estimated the risk of incidence of painful events at 5 % per year. Even lower risk (1–2 %) was reported from a cohort of 1032 root-filled teeth followed over time by Van Nieuwenhuysen et al. [79]. In a report from a university hospital clinic in Singapore, flare-ups in non-healed root-filled teeth occurred only in 5.8 % over a period of 20 years. However, less severe pain was experienced by another 40 % [83]. There have also been studies conducted in order to investigate if inflammatory processes of endodontic origin have an impact on the incidence of cardiovascular disease, but the results are contradictive [12, 15, 25].

Regarding the reason for referrals to specialist clinics, one study showed the main reason to be cases with an already root-filled tooth, followed by inability to control pain or to decide the correct diagnosis [29]. An Australian study found similar results, but with management of pain and technical difficulties outweighing the retreatment cases [1].

Variation in Clinical Decisions Regarding the Failed Root Treatments

The diagnostic difficulties, timing, the question of what should be regarded as healthy and diseased and several other factors partly explain the large variation among dentists regarding retreatment decision-making. This situation has been highlighted in numerous publications in recent years [40, 41, 62, 70]. From the bulk of investigations conducted, it stands clear that the mere diagnosis of apical periodontitis in a root-filled tooth does not consistently result in decisions for retreatment among clinicians. Theoretically four options are available. If retreatment is selected the decision-maker also has to make a choice between a surgical or nonsurgical approach:

-

No treatment

-

Monitoring

-

Extraction

-

Retreatment

-

Nonsurgical

-

Surgical

-

Patient Values

Given equal information and similar diagnostic findings, dentists will not invariably make the same clinical decision of a root-filled tooth with apical periodontitis. Neither will different patients choose the same clinical management despite identical information about apical periodontitis or any other disease by that matter. Both doctors’ and patients’ values will influence the decision-making process. The concept of value has many aspects, but it is reasonable to suppose that there is a close connection between an individual’s values and his or her preferences and value judgements. The concept of personal values in clinical decision-making about apical periodontitis has been explored among both dental students and specialists by Kvist and Reit [39]. Substantial interindividual variation was registered in the evaluation of asymptomatic apical periodontitis in root-filled teeth. From a subjective point of view, some patients will benefit much more from endodontic retreatment than others.

Today patient autonomy is widely regarded as a primary ethical principle, emphasizing the importance of paying attention to the values and preferences of the individual patient.

Informed Consent

In the clinical situation, the requirement of respect for individual autonomy and integrity is managed through the concept of informed consent. The requirement that a medical or dental action should be preceded by informed consent is deemed very important in medical ethics [4].

The informed consent has two components: information and consent. But it is not enough that a patient has received written or oral information and then provided an informed consent. The patient must have accepted and understood the information and not only received it. All the relevant aspects of the situation should be informed about in a relevant way. It is also important that the patient has not misunderstood something he or she thinks is important for the decision. The dentist should not only convey information but also need to ensure that the information is correctly understood. In order to take a position in an independent way in a choice situation, the patient must be informed about the meaning of the alternatives, have understood the information and be free to choose, i.e. not be subjected to compulsion, or in such a position of dependence that the free informed choice becomes an illusion.

In a modern dental surgery, there are many situations that can hamper patient’s ability to acquire and rationally process the information given. The environment may seem daunting and lead to both anxiety and worry, which can blur a generally well-functioning sense and judgement. To ascertain that the patient understands the information may thus be difficult. It is therefore important that the dentist is attentive to both verbal and non-verbal expressions.

Since many facts about the consequences of asymptomatic apical periodontitis in root filled are unknown, it is important that patients are free to choose what option they prefer. At the same time, one must have realistic expectations of the patient’s ability to understand and evaluate the options – this can vary greatly between individuals. For patients who want to have full control over the decision, doctors should make sure to make this possible, but one must also allow the patient to hand over a part of decision-making if he or she so wishes. A professional reception of each individual patient at the dentist’s office creates a seedbed for high confidence that the patient can feel safe with both for the decision-making and the treatment.

The medical ethical debate about informed consent is concerned not only on how information should be handled but also the forms of consent. In everyday clinical practice, an oral consent is normal and also appears naturally. A written agreement could be seen as well formal and might also get the patient to wonder what kind of exceptional measures that require such formalities. However, in many countries and in research contexts, it is quite common or even compulsory with written informed consent documentation.

Information About Treatment

One patient in the dental care can hardly be expected to have knowledge and understanding of all the factors that can and should be taken into consideration before a clinical decision about endodontic surgery. The patient has the right to know what the treatment entails, how risky and painful it is and what impact it is likely to bring with them to undergo treatment and to refrain from it. This implies a corresponding requirement for dental staff to ensure that this information is provided and that it is done in a way that the patient can actually understand. In practice, of course, there is a limit to how detailed the information can and should be. As long as the choice of methods, equipment and materials to carry out an endodontic surgery is considered as the standard, there is no reason to go into small details. If the patient asks many questions about the equipment and methods, this can be an expression of concern or, at worst, distrust rather than a genuine desire for more detailed information. As important as providing answers to all the questions then it is to try to establish or re-establish trust. The patient should be able to rely on dentist’s knowledge based on science and proven experience and that they follow both the technological and scientific developments in the field. They should also be confident that the dentist has the best for the patient as their primary goal.

Information About Risks

For completeness of the information something must be said about the risks associated with the suggested treatment and about refraining from treatment. In this particular case, this is complicated significantly due to the fact that evidence is lacking about how the untreated apical periodontitis affects individuals both locally and systemically.

There are two basic aspects of risk: some kind of negative consequence and the probability that it will occur. The negative consequence or injury may be more or less severe. The most serious negative consequences in health care, including dentistry, are life-threatening. Such consequences are also highly unusual in dental practice including surgical procedures.

It is clearly important to inform the patient in the case of relatively high probability of severe consequences (if any treatments at all should be carried out), while it seems unimportant to communicate very unlikely minor damages. In many other cases, it is difficult to know how to do. If there had been only advantages to inform there would have been no reason to hesitate. What complicates the matter is that information in itself can cause injury. First, risk information may cause anxiety, and it can make patients refrain from treatments because of unrest despite that the risks otherwise would be reasonable to accept. This is why there may be reason to wonder, for example, whether to communicate a very small likelihood of great harm. Primarily because it is a concern from dentist’s point of view to promote patient’s oral health, but also from the autonomy perspective, it is sometimes questionable whether such information should be given. The fear of an unlikely but serious injury may counteract the ability of the patient to rationally reflect on the options and come to an autonomous decision. Exactly what considerations that should be made are debatable. How much and what to inform varies with the situation and who is the patient. Some patients prefer not to know the risks unless it is clearly relevant. The dentist needs to know in advance both those who are keen to get information and those who would prefer to avoid. If the patient visited the practice on a regular basis for several years and is well known, it may be possible for the dentist to give properly balanced information. But as in the case of endodontic surgery, where many patients have been referred to an endodontist or oral surgeon specifically for this treatment, the dentist is lacking this knowledge of the patient. Being in this situation, to ask the patient if he or she wants risk-related information does not work well because the patient will then easily conclude that the caregiver has important risk information because otherwise he or she would not have asked.

Information on Costs

When deciding about a tooth in need of endodontic surgery the economic aspect of the treatment is often one, if not decisive, then at least very important factor. Since surgical endodontics does not require the dismantling of functional prosthodontics constructions, it is often a less expensive alternative for the patient. But the costs of both surgical and nonsurgical treatment of course vary both in different countries between operators and between countries with different systems of reimbursement by insurance. It is important that information about the costs and possible reimbursement by insurance are correct and that it does not change.

Information and Manipulation

When the patient is informed about the facts regarding diagnoses, treatment options, risks and costs, he or she must be allowed to choose what she or he wants to do in the given situation. The individual has a right not to be forced or manipulated to undergo medical or dental treatments. However, it is difficult to imagine that the dentist can completely avoid the influence. The positive approach to good oral and dental health and, in this particular case, the importance of restoring periapical health are likely to affect the patient to some degree. One might think that it is also reasonable, since good periapical health is in the interests of the patient. Here, there is an important balancing act so that patient autonomy is not compromised. The endodontist or oral surgeon must develop sensitivity to patients’ varying values and preferences. Particularly important is the responsiveness if the patient’s ability to exercise their autonomy is compromised.

Authorized Informed Consent

Many patients lack all or part of the capacity for autonomous decision-making. It may involve children, mentally ill, mentally retarded or demented individuals. It is important to remember that these patients have the right to be treated with care and respect. A fruitful way to address the challenge of information and consent for these patients is to allow them to exercise their autonomy as best they can, and otherwise let them express their willingness or unwillingness to cooperate.

In the absence of the ability to understand, to take a stand and to make decisions, the informed consent can be authorized to a close relative or another person close to the patient.

Summary

Social development has led to the conclusion that we are currently seeing the patient’s right to autonomous decision-making as an integral part of both dental care and other health services. Procedures for obtaining informed consent play a key role in safeguarding this right. In the context of endodontic surgery, informed consent means that the patient after having been informed of and understand the relevant aspects of the offered surgical procedure may determine whether to say yes or no to the dentists’ suggestion of treatment. The information shall include a description of the course of treatment, the pros and cons of the surgery, and what it costs. Whether to perform a retreatment or not is a complex decision-making situation. Many factors have to be considered. For the dentist who made the diagnosis and who is about to suggest a treatment, both biological considerations and the potential and limitations of different options have to be deliberated. Equally important are the preferences of each individual patient. The subjective meaning of the situation will vary among patients. Only the patient is the expert on how he or she feels about keeping a tooth with or without retreatment or perhaps extracting it, which symptoms are tolerable, which risks are worth taking and what costs are acceptable.

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses