Learning Objectives

After reading this chapter, the student should be able to:

- 1.

Identify the causes and nature of tooth discoloration.

- 2.

Describe means of preventing coronal discolorations.

- 3.

Differentiate between dentin and enamel discolorations.

- 4.

Evaluate both the short-term and long-term prognoses of bleaching treatments.

- 5.

Select the bleaching agent and technique according to the cause of discoloration.

- 6.

Describe each step of the internal “walking bleach” technique.

- 7.

Describe the indications for the microabrasion technique and the procedure.

- 8.

Describe how bleaching agents may alter dentin.

- 9.

Select the appropriate method to restore the access cavity after bleaching.

- 10.

Recognize the potential adverse effects of bleaching and discuss means of prevention.

Discoloration of anterior teeth is a cosmetic problem that is often significant enough to induce patients to seek corrective measures. Although restorative methods, such as crowns and veneers, are available, discoloration can often be corrected totally or partially by bleaching.

Bleaching procedures are more conservative than restorative methods, relatively simple to perform, and less expensive. Procedures may be internal (within the pulp chamber) or external (on the enamel surface) and involve various approaches. The objectives of treatment are to reduce or eliminate discoloration, improve the degree of coronal translucency, and alleviate present and prevent future clinical signs and symptoms.

To better understand bleaching techniques, it is important to know the causes of discoloration, location of the discoloring agent, and treatment modalities available. Also important is the ability to predict the outcome of treatment (i.e., how successfully various discolorations can be treated and how long the esthetic result will last). Therefore, before attempting to correct discoloration, there must be a diagnosis (to determine the cause and location of the discoloration), a treatment plan (internal or external bleaching and the technique), and a prognosis (anticipated short- and long-term success). Patients must be informed of these factors before undergoing the procedure; any discoloration treatment is tempered by the explanation that bleaching is somewhat unpredictable and that substantial improvement may or may not occur. However, bleaching is worth a try because with proper and careful technique, no irreversible damage to the crown or root occurs.

This chapter reviews internal tooth discoloration and its prevention and correction. Discussed are the causes and management of discoloration as related to (1) the location of the discoloration, (2) the approach used for correction, and (3) the predicted short- and long-term success of bleaching. The following aspects of discoloration and bleaching procedures are discussed:

- 1.

Causes and location of discoloration

- 2.

Commonly used bleaching agents

- 3.

Internal bleaching techniques (usually in conjunction with or after root canal treatment)

- 4.

Microabrasion, (a technique for removing surface discolorations)

- 5.

Predictability and permanence of each procedure

- 6.

Possible complications and safety of the various procedures

Learning Objectives

After reading this chapter, the student should be able to:

- 1.

Identify the causes and nature of tooth discoloration.

- 2.

Describe means of preventing coronal discolorations.

- 3.

Differentiate between dentin and enamel discolorations.

- 4.

Evaluate both the short-term and long-term prognoses of bleaching treatments.

- 5.

Select the bleaching agent and technique according to the cause of discoloration.

- 6.

Describe each step of the internal “walking bleach” technique.

- 7.

Describe the indications for the microabrasion technique and the procedure.

- 8.

Describe how bleaching agents may alter dentin.

- 9.

Select the appropriate method to restore the access cavity after bleaching.

- 10.

Recognize the potential adverse effects of bleaching and discuss means of prevention.

Discoloration of anterior teeth is a cosmetic problem that is often significant enough to induce patients to seek corrective measures. Although restorative methods, such as crowns and veneers, are available, discoloration can often be corrected totally or partially by bleaching.

Bleaching procedures are more conservative than restorative methods, relatively simple to perform, and less expensive. Procedures may be internal (within the pulp chamber) or external (on the enamel surface) and involve various approaches. The objectives of treatment are to reduce or eliminate discoloration, improve the degree of coronal translucency, and alleviate present and prevent future clinical signs and symptoms.

To better understand bleaching techniques, it is important to know the causes of discoloration, location of the discoloring agent, and treatment modalities available. Also important is the ability to predict the outcome of treatment (i.e., how successfully various discolorations can be treated and how long the esthetic result will last). Therefore, before attempting to correct discoloration, there must be a diagnosis (to determine the cause and location of the discoloration), a treatment plan (internal or external bleaching and the technique), and a prognosis (anticipated short- and long-term success). Patients must be informed of these factors before undergoing the procedure; any discoloration treatment is tempered by the explanation that bleaching is somewhat unpredictable and that substantial improvement may or may not occur. However, bleaching is worth a try because with proper and careful technique, no irreversible damage to the crown or root occurs.

This chapter reviews internal tooth discoloration and its prevention and correction. Discussed are the causes and management of discoloration as related to (1) the location of the discoloration, (2) the approach used for correction, and (3) the predicted short- and long-term success of bleaching. The following aspects of discoloration and bleaching procedures are discussed:

- 1.

Causes and location of discoloration

- 2.

Commonly used bleaching agents

- 3.

Internal bleaching techniques (usually in conjunction with or after root canal treatment)

- 4.

Microabrasion, (a technique for removing surface discolorations)

- 5.

Predictability and permanence of each procedure

- 6.

Possible complications and safety of the various procedures

Causes of Discoloration

Tooth discolorations may occur during or after enamel and dentin formation. Some discolorations appear after tooth eruption, and others are the result of dental procedures. Acquired (natural) discolorations may be on the surface or incorporated into tooth structure. Sometimes they result from flaws in enamel or a traumatic injury. Inflicted (iatrogenic) discolorations, which result from certain dental procedures, are usually incorporated into tooth structure and are largely preventable.

Acquired (Natural) Discolorations

Pulp Necrosis

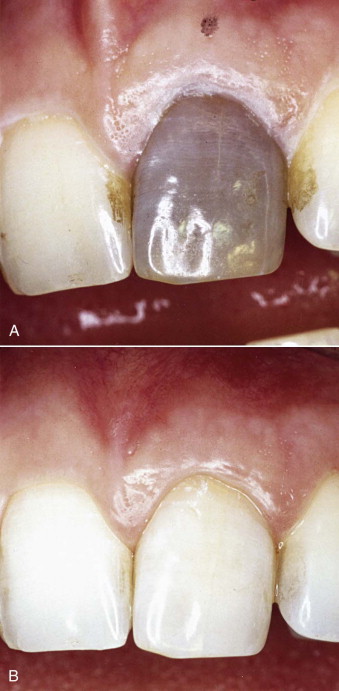

Bacterial, mechanical, or chemical irritation of the pulp may result in necrosis. Tissue disintegration byproducts are then released, and these colored compounds may permeate tubules to stain surrounding dentin. The degree of discoloration is likely related to how long the pulp has been necrotic. The longer the discoloration compounds are present in the pulp chamber, the greater the discoloration. This type of discoloration can be bleached internally, usually with both short- and long-term success ( Fig. 24.1 ).

Intrapulpal Hemorrhage

Intrapulpal hemorrhage is usually associated with an impact injury to a tooth that results in disrupted coronal blood vessels, hemorrhage, and lysis of erythrocytes. It has been theorized that certain blood disintegration byproducts, presumably iron sulfides, permeate tubules to stain surrounding dentin. Discoloration tends to increase with time.

If the pulp becomes necrotic, the discoloration usually remains. If the pulp survives, the discoloration may resolve and the tooth regains its original shade. Sometimes, mainly in young individuals, the tooth remains discolored even if the pulp responds to vitality tests.

Internal bleaching of discoloration after intrapulpal hemorrhage is usually successful both short term and long term.

Calcific Metamorphosis

Calcific metamorphosis is extensive formation of tertiary (irregular secondary) dentin in the pulp chamber or on canal walls. This phenomenon usually follows an impact injury that did not result in pulp necrosis. There is likely temporary disruption of the blood supply with partial destruction of odontoblasts. These are usually replaced by cells that rapidly form irregular dentin on the walls of the pulp chamber and root canal space. As a result, the crowns take on a “flat” appearance as they gradually decrease in translucency and acquire a yellowish or yellow-brown discoloration ( Fig. 24.2 ). The pulp usually remains vital and does not require root canal treatment.

If the patient desires color correction, external bleaching should be attempted first. If this is unsuccessful, root canal treatment is performed (sometimes with difficulty), and internal bleaching is done. This may be carried out whether the pulp is vital or necrotic. The esthetic prognosis for such bleaching is fair (unpredictable).

Age

In older patients, color changes in the crown occur physiologically as a result of extensive dentin apposition and thinning of and optical changes in the enamel. Food and beverages also have a cumulative discoloring effect because of the inevitable cracking and other changes on the enamel surface and in the underlying dentin. In addition, previously applied restorations that degrade over time cause further discoloration. There is an increasing demand for bleaching among elderly patients. Bleaching is usually external because the discoloration is primarily on the enamel surface. Success may vary, depending on the causal factor of discoloration.

Developmental Defects

Discolorations may also result from development defects or from substances incorporated into enamel or dentin during tooth formation.

Endemic Fluorosis

Ingestion of excessive amounts of fluoride during tooth formation produces defects in mineralized structures, particularly enamel matrix, with resultant hypoplasia. The severity and degree of subsequent staining generally depend on the degree of hypoplasia, which depends in turn on the patient’s age and the amount of fluoride ingested during odontogenesis. The teeth are not discolored on eruption but may appear chalky. Their surface, however, is porous and gradually absorbs stains from chemicals in the oral cavity.

Because the discoloration is in the porous enamel, such teeth are bleached (or corrected) externally. Esthetic success depends mainly on the degree and duration of the discoloration. Some regression and recurrence of discoloration tend to happen but can be corrected with future rebleaching.

Systemic Drugs

Administration or ingestion of certain drugs or chemicals (many of which have not yet been identified) during tooth formation may cause discoloration, which is occasionally severe.

The most common and most dramatic discoloration of this type occurs after tetracycline ingestion, usually in children. Discoloration is bilateral, affecting multiple teeth in both arches. It may range from yellow through brownish to dark gray, depending on the amount, frequency, and type of tetracycline and the patient’s age (stage of development) during administration.

Tetracycline discoloration has been classified into three groups according to severity. First-degree discoloration is light yellow, light brown, or light gray and occurs uniformly throughout the crown without banding. Second-degree discoloration is more intense and is also without banding. Third-degree discoloration is very intense, and the clinical crown exhibits horizontal color banding. This type of discoloration usually predominates in the cervical region.

Tetracycline binds to calcium, which then is incorporated into the hydroxyapatite crystal in both enamel and dentin. Most of the tetracycline, however, is found in dentin. Chronic sun exposure of teeth with the incorporated drug may cause formation of a reddish purple tetracycline oxidation byproduct, resulting in further discoloration of permanent teeth.

A phenomenon of adult-onset tetracycline discoloration has also been reported. This type of discoloration occurs occasionally in mature teeth in patients receiving long-term minocycline therapy, which was usually given for control of cystic acne. The discoloration is gradual because of incorporation of minocycline in continuously forming dentin. Staining generally is not severe.

Two approaches have been used for bleaching tetracycline discoloration. The first, which involves bleaching the external enamel surface, is limited to lighter, yellowish discoloration and requires multiple appointments to achieve a satisfactory result. The second, root canal treatment followed by internal bleaching, is a predictable procedure, is useful for all degrees of discoloration severity, and has proved successful in both the short term and long term.

Defects in Tooth Formation

Defects in tooth formation are confined to the enamel and are either hypocalcific or hypoplastic. Enamel hypocalcification is common, appearing as a distinct brownish or whitish area, often on the facial aspect of a crown. The enamel is well formed and intact on the surface and feels hard to the explorer. Both the whitish and the brownish spots are amenable to correction with the pumice and acid technique (described later in this chapter) with good results.

Enamel hypoplasia differs from hypocalcification in that the enamel in the former is defective and porous. This condition may be hereditary (amelogenesis imperfecta) or may result from environmental factors. In the hereditary type, both deciduous and permanent dentitions are involved. Defects caused by environmental factors may involve only one or several teeth. Presumably during tooth formation the matrix is altered and does not mineralize properly. The porous enamel readily acquires stains from the oral cavity. Depending on the severity and extent of hypoplasia and the nature of the stain, these teeth may be bleached (or corrected by the acid pumice method) from the enamel surface with some degree of success. The bleaching effect may not be permanent, and stains may recur with time. These stains, however, can be recorrected. As stated earlier, it is most important to inform the patient of the likely recurrence of discoloration of these teeth.

Blood Dyscrasias and Other Factors

Various systemic conditions may cause massive lysis of erythrocytes. If this occurs in the pulp at an early age, blood disintegration products are incorporated into and discolor the forming dentin. An example of this phenomenon is the severe discoloration of primary teeth that usually follows erythroblastosis fetalis. This disease in the fetus, or newborn, results from Rh incompatibility factors, which lead to massive systemic lysis of erythrocytes. Large amounts of hemosiderin pigment then stain the forming dentin of the primary teeth. This discoloration is not correctable by bleaching. However, this type of lysis is now uncommon because of new preventive measures.

High fever during tooth formation may result in linear defined hypoplasia. This condition, known as chronologic hypoplasia, is a temporary disruption in enamel formation that results in a banding type of surface defect that acquires stain. Porphyria, a metabolic disease, may cause deciduous and permanent teeth to show a red or brownish discoloration. Hyperbilirubinemia, thalassemia, and sickle cell anemia may cause intrinsic bluish, brown, or green discolorations. Amelogenesis imperfecta may result in yellowish or brownish discolorations. Dentinogenesis imperfecta can cause brownish violet, yellowish, or gray discoloration. These conditions are also not amenable to bleaching and should be corrected by minimally invasive restorative means.

Other staining factors related to systemic conditions or ingested drugs are rare and may not be identifiable.

Inflicted (Iatrogenic) Discolorations

Discolorations caused by various chemicals and materials used in dentistry are usually avoidable. Many of these discolorations respond well to bleaching, but some are more difficult to correct by bleaching alone.

Endodontically Related Discolorations

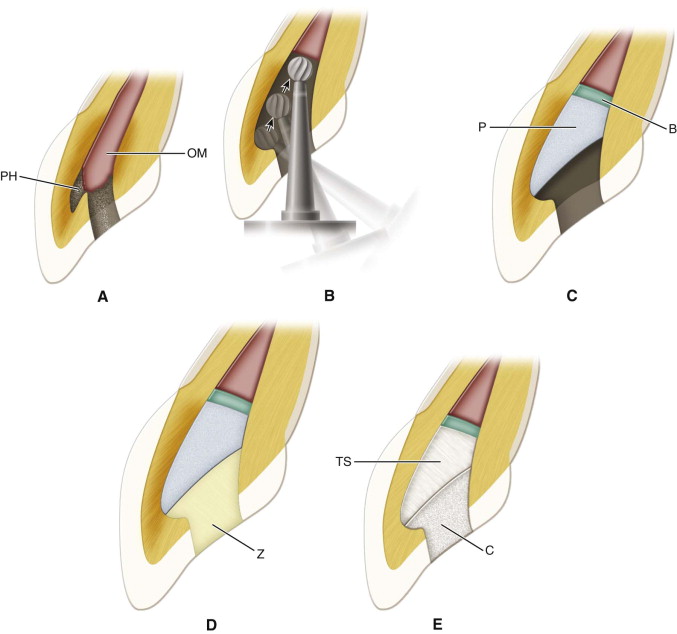

Obturating Materials

Obturating materials are the most common and severe cause of single tooth discoloration. Incomplete removal of materials from the pulp chamber upon completion of treatment often results in dark discoloration ( Figs. 24.3 and 24.4 ). Removing all obturation materials to a level just cervical to the gingival margin can prevent such discoloration. Primary offenders are sealer remnants, whether of the zinc oxide–eugenol type or resins, which themselves also darken with time. Sealer remnants gradually cause progressive coronal discoloration. The prognosis of bleaching in such cases depends on the constituents of the sealer. Sealers with metallic components often do not bleach well, and the bleaching effect tends to regress with time.

Remnants of Pulpal Tissue

Pulp fragments remaining in the crown, usually in pulp horns, may cause gradual discoloration. Pulp horns must be “opened up” and exposed during access preparation to ensure removal of pulpal remnants and to prevent retention of sealer at a later stage. Internal bleaching in such cases is usually successful ( Fig. 24.5 ).

Intracanal Medicaments

Several medicaments have the potential to cause internal discoloration of the dentin. Phenolic or iodoform-based intracanal medications, sealed in the root canal space, are in direct contact with dentin, sometimes for long periods, which allows penetration to dentin tubules and oxidization. These compounds have a tendency to discolor the dentin gradually. Fortunately, most such discolorations are not marked and are readily and permanently corrected by bleaching. Iodoform-induced discolorations tend to be more severe.

Coronal Restorations

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses