Simple extractions are procedures that are becoming less common in today’s dental world because preventative dentistry and advanced dental techniques have evolved to be able to more successfully maintain and save teeth from being removed. Awareness about the importance of maintaining dentition has also played a significant role in extractions becoming a last resort as a modality for dental treatment.

The relatively recent onset of high-tech dentistry produced a greater shift toward achieving not only successful lasting results, but highly cosmetic and more predictable results. The basis of exodontia has evolved as well to incorporate a higher degree of technique improvement, treatment planning, and diagnosis and timing of replacement treatment to be included in the work-up of the extraction process. As tooth replacement has become the more commonly accepted treatment, rather than the abandonment of the extraction site as in the past, clinicians find themselves involved in the management of the extraction site as a part of a simple extraction procedure.

The definition of basic exodontia involves simple luxation techniques, bone expansion, and forceps delivery. The clinician must pay attention in greater detail to diagnostic tools, such as x-rays, and employ them to appropriately consider root form abnormalities, root canal therapies, and other various factors when planning on simple extraction. If these small details and basic biologic principals are not paid attention to and respected, the surgeons might find themselves suddenly dealing with a complicated or surgical exodontia rather than a simple extraction.

When a problem is anticipated in the process of diagnosis and treatment planning, then one should prudently proceed to planning for surgical extraction to preserve the bony socket and periodontal apparatus.

▪

INDICATIONS

DECAY

Decay is one of the most common reasons leading to tooth extraction. Decayed teeth will fall into one of two categories: restorable or nonrestorable decayed teeth. Although the extraction process itself might be a simple procedure, the decision is not always as simple.

Thorough examination should first take place and studying of the radiographs in conjunction with the clinical findings as well should be an intricate part of the decision process. In cases of nonrestorable decayed teeth, one must pay extreme care to treatment planning because some teeth could fracture during the extraction process and lead to a surgical extraction rather than simple extraction. If possible, it is always prudent to plan for a surgical extraction and proceed with sectioning the roots or laying a surgical flap for better preservation of the alveolar bone and periodontal apparatus.

Unfortunately, some patients that have decayed but restorable teeth would like to have their teeth removed for financial reasons. Although there is not enough room in this chapter to discuss the ethical dimension of such a decision, the clinician must always spend time counseling the patient regarding the various options that are available to try to preserve the tooth.

▪

PERIODONTAL DISEASE

When periodontal disease has progressed so far that it has caused significant bone and periodontal loss and deemed the tooth nonrestorable, the obvious answer is simple tooth extraction and an attempt to regenerate and preserve that site in preparation for other various prosthetic restoration.

Periodontal disease around fully or partially erupted third molars has been well studied also and has shown to contribute to medical systemic illnesses. Should periodontal disease be uncontrollable with surgical methods, one must always consider the option of extraction as a solution as part of the preventative medical management.

▪

PERIODONTAL DISEASE

When periodontal disease has progressed so far that it has caused significant bone and periodontal loss and deemed the tooth nonrestorable, the obvious answer is simple tooth extraction and an attempt to regenerate and preserve that site in preparation for other various prosthetic restoration.

Periodontal disease around fully or partially erupted third molars has been well studied also and has shown to contribute to medical systemic illnesses. Should periodontal disease be uncontrollable with surgical methods, one must always consider the option of extraction as a solution as part of the preventative medical management.

▪

ORTHODONTICS

The requests for orthodontic extractions of first premolars have dramatically decreased as a result of a shift in the thinking process in orthodontic treatment planning. Except in cases of severe crowding, extractions of premolars are less common. Rather orthodontic treatment planning today leans more toward setting the anterior dentition in a more protrusive position, taking into consideration lip support, future skeletal growth change, and its facial cosmetic impact. Evolution of various orthodontic technologies leading to better anchorage, such as the orthodontic minianchor implants, is changing treatment planning as well. However, cases of extreme crowdedness do sometimes necessitate the extraction of premolars, anterior lower centrals, or sometimes molars or premolars with large restorations.

The treatment planning must be very clearly communicated between the orthodontic specialist who is managing the orthodontic care and the surgeon who is removing the teeth. The treatment plan must be of sound clinical judgment.

▪

TOOTH FRACTURE

Tooth fracture is a common, but sometimes difficult, condition to diagnosis, especially in its early stages because the radiographic evidence cannot always be helpful and a vertical fracture cannot always be detected with the naked eye.

The diagnosis comes most of the time from an endodontist who attempted to treat the tooth endodontically with microscopic magnification; he or she tends to see the fracture in the base of the pulp chamber and make the appropriate referral.

Other fractured teeth with obvious clinical presentation that deem the crown nonrestorable as a result of the extension of the fracture into the furcation or deep into the subosseous level should be considered for evaluation. Some subosseous fractures could be considered for salvaging by crown lengthening procedures and orthodontic eruption, yet some are too deep to salvage that way and must be extracted.

Careful treatment planning should consider the clinical condition of the tooth, plan simple extraction versus surgical extraction, and then proceed accordingly.

▪

PREPROSTHETIC PREPARATION

In treatment planning for fabricating a fixed or removal prosthesis, it would sometimes be necessary to remove carious nonrestorable teeth or noncarious teeth because of their severe malposition or supereruption. In fixed prosthetic cases, sometimes the decision is made to remove severely rotated or malerupted teeth for lack of their value in anchorage or for their negative impact on the cosmetic outcome.

If maxillary or mandibular teeth were removed and not replaced for a long time, the opposing and adjacent teeth will undergo supereruption and shifting. Sometimes salvaging these teeth or restoring them to a functional status could involve heroic effort and extensive treatment interventions that would have a significant impact on the time and cost of treatment.

The decision to have these teeth removed also needs to be very carefully discussed with the prosthodontist who will be making the final decision on the design of the prosthetic work and the engineering of the occlusal force distribution on the final prosthesis. Patient education about the various options, the risk involvement versus the benefits, is extremely important. In some instances, a few anterior teeth might be remaining, simply for cosmetic value from the patient’s perspective. These teeth could have very little to no value for full anchorage of a partial denture, and a prosthetic decision might have to be made to have these removed and alter the design into a full denture for better stability and cosmetic outcome.

Combination syndrome is a condition that still is found commonly in general dentistry practice, and it must be very prudently prevented. Should the patient have a maxillary full removable prosthesis and partial remaining anterior teeth only, analysis of the occlusal forces must be carefully studied and the patient must be counseled about combination syndrome scenario. Fabrication of either a new partial lower prosthesis that would provide a stable posterior occlusal support and/or removal of the anterior teeth and conversion of the lower mandibular prosthesis into a full arch removable denture should be suggested.

▪

REVERSIBLE PULPITIS

With surgeons mastering the techniques of implantology and with improvement of implant surfaces, the success of implants have become very predictable and studies have shown that implants are as successful or more successful than root canal therapy. When root canals were done by endodontists, the success rate was found to be between 70% to 95%. It was even lower than that when the root canals were performed by general practitioners.

Root canals that failed secondary to nonsurgical endodontics did so because of periodontal disease, dental decay, vertical root fracture, and a variety of other reasons.

▪

TEETH ASSOCIATED WITH PATHOLOGIC CONDITIONS

Because some pathologic conditions will develop under the apices of mandibular or maxillary teeth, treatment for these pathologic conditions could require a thorough and aggressive curettage and removal to cure the lesion. Good surgical access and visibility is essential to prevent damaging some vital structures, such as the inferior alveolar nerve. The clinician must make that decision and carefully evaluate, aided by clinical examination, incisional biopsies, and radiographic studies, to find out if the teeth adjacent to the pathologic conditions need to be sacrificed for access and successful removal of the lesion.

▪

CHEMOTHERAPY AND RADIATION

The significant focus and research of cancer over the past decades have led to the development of some very effective chemotherapeutic agents that have led to a dramatic extension of the life span of cancer patients. In some cases, these therapies have even achieved a cure for some treated cancers. These agents unfortunately come with a significant list of side effects. Most significant of these effects is the impact on the immune system and the healing abilities of the body. Because these are life-preserving medications in most instances, one must learn how to deal with the negative outcome of side effects in the most efficient manner to afford a suitable quality of life for the patient.

▪

DIAGNOSIS AND TREATMENT PLANNING

Appropriate and careful studying of the situation, assessing the difficulty of the extraction, and collecting relevant information would lead to appropriate treatment planning and preparation for a simple versus surgical extraction. A well-planned procedure will lead to a more comfortable visit for both surgeon and patient and a more successful, predictable outcome reflecting positively on the surgeon’s efficiency, valuable chair time, and reputation.

Once the surgeon has collected the various diagnostic data, one must share the information with the patient and use it for a good session of preoperative patient education, explaining to the patient a reasonable surgical course and postoperative strategies and expectations.

Vallerand et al. demonstrated the positive effect of an informative preoperative session regarding the postoperative expectations in significantly increasing pain relief and the positive outcome of satisfaction with pain control without increasing medications.

An important part of diagnosis and treatment planning is collecting medical data, review of the patient’s medical history, current medications and their potential impact on the patient’s healing ability, bleeding, immune system, and potential interactions with postoperative medications prescribed by the surgeon. The patients must also be counseled regarding smoking and its negative effect on the healing socket and the alveolar process, bony dimensions, and the effect of smoking on the dimensional reduction of the residual alveolar bone and its potential negative impact on the patient’s ability to replace the extracted tooth postoperatively either by a bridge or an implant.

Thorough clinical examination of the object tooth itself and the surrounding structures must take place. The patient’s ability to open wide enough to grant good access and visual field must be evacuated. The presence of TMJ disease or trismus limiting the patient to open wide must be appraised as well. Any swelling in the area of the planned extraction site must be assessed and determined if it is a peridental abscess versus neoplasm. If neoplasm is suspected, one must prudently reassess and delay the extraction if possible until further confirmation with a biopsy has been performed. If swelling was due to a dental abscess, then one must plan accordingly and realize the potential negative impact of the abscess on the surgeon’s ability to administer an effective local anesthetic.

Then a thorough clinical examination of the tooth itself and the extent of decay or large restorations that might lead to tooth fracture is performed, converting the case into a surgical extraction versus simple extraction. Examination of radiographic evidence, such as panoramic and periapical x-rays, must take place to assess the roots of the teeth and the surrounding area. Dilacerated roots, bulbous roots, thin long roots with thin curved ends, ankylosed roots, and the intimate proximity of these roots to the anatomic structures, such as the maxillary sinus and inferior alveolar nerve, must all be considered in forming a treatment plan.

Once all of the data has been thoroughly collected and analyzed, the surgeon will proceed with a specific treatment plan and he or she will be able to execute it with a greater degree of comfort and predictability.

▪

PRINCIPLES OF SIMPLE EXTRACTION

In the process of a simple extraction, the surgeon must exercise a great deal of finesse and a certain degree of controlled force to be able to deliver a simple tooth extraction. If the surgeon finds himself or herself in a situation where they have to exercise a lot of force to be able to deliver a certain tooth extraction, they must stop and reassess the situation before resuming.

As mentioned earlier, a simple extraction process involves minor alveolar bone expansion, separation of the periodontal ligament, and simple coronal forceps delivery of the tooth. Successful extractions also depend on the surgeon’s thorough and detailed understanding of the anatomy of the teeth involved, the root form, angulation, their attachment to the periodontal apparatus, and the bony structure underneath.

Experience will enhance the surgeon’s tactile sense. As the tooth is being removed, the surgeon will be able to appreciate the lateral forces applied on the tooth’s roots and their effect on the alveolar bone. This will lead to avoidance of any excessive forces that would produce root and alveolar bone fracture.

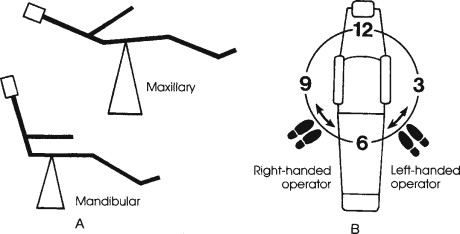

The patient needs to be positioned in the dental chair to allow for the surgeon’s optimal control and visibility. When extractions are being performed in the lower arch, it is preferable that the patient’s mandible is positioned in a parallel line with the floor. Then the patient’s height should be adjusted up and down to allow for the mandible to be positioned at the same level at the surgeon’s elbow so that when the surgeon is performing the extraction, the forearm is parallel with the floor as well. When extracting a maxillary tooth, the patient’s maxillary occlusal plane should fall at almost a 60° angle with the floor.

The surgeon’s position, relative to the patient’s position, varies as well, depending on which tooth is being extracted. It is also dependant on the surgeon’s dominant hand ( Figure 11-1 ).

Using the appropriate specialized instrumentation facilitates the procedure and makes it more predictable. Typically the surgeon will start by separating the superior portion of the periodontal ligament, then subluxating with an elevator. Choosing the right forceps is important to be able to grasp the cervical portion of the tooth and position it as apically as possible to try to shift the center of rotation toward the root. This allows the most effective central bone expansion movement and prevention of the fracture of roots or crown at the same time. Sharp elevators and forceps are always more desirable to use because they will engage the tooth in a more firm and predictable manner and prevent slippage and/or lack of efficient delivery of force.

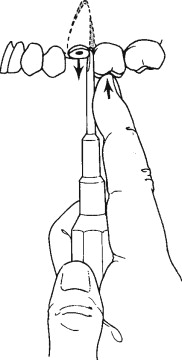

Pursuant to the separation of the periodontal ligament, one must find an appropriate purchase point for the elevator, try to position the elevator between the bony socket wall and the tooth itself, and direct the elevator in an apical direction trying to subluxate the root and push it coronally. Most of the time an effective elevation would prevent injury to the adjacent teeth, maintain the integrity of the alveolar bony structure, and make the forceps delivery extremely simple. During the introduction of the elevator, the surgeon’s free hand should, if possible, always hold the alveolar process with the thumb on one side and the forefinger on the other side and try to sense and direct the degree and direction of force being applied to the alveolar process of the tooth ( Figure 11-2 ).

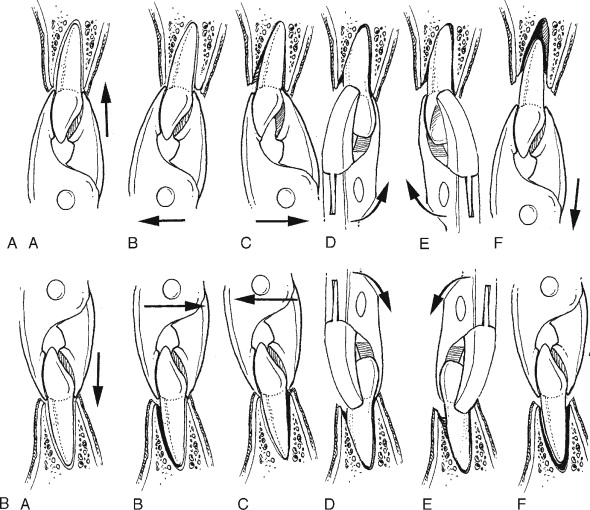

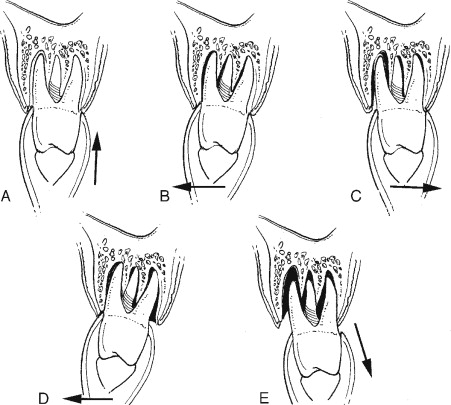

When extracting one of the maxillary anterior lateral and central incisors and/or mandibular premolars, the predominant extraction force is mainly rotational with the use of a universal maxillary forceps #150 for the maxillary teeth and an Asch forceps for the lower teeth ( Figure 11-3 ). The maxillary canines and the lower anterior teeth, however, seem to have flatter roots and would require more lateral buccal and lingual forces application in the process of the extraction first. The maxillary premolars could have roots that are thin. A maxillary universal forceps is typically used for these teeth to be extracted. The forceps is positioned to grasp the crown portion of the tooth and seated as apically as possible. Lateral force in a buccal fashion is applied first and then in the palatal aspect with extreme care to prevent fracturing those thin roots. Careful repetition of the same movement is done until the tooth is subluxated. The alveolar bone is expanded, and the tooth can then be delivered coronally ( Figure 11-4 ).

A very similar technique is used for the maxillary molars as well. Great attention must be paid not to cause excessive force, which could fracture the buccal plate. A variety of other maxillary forceps have been designed to allow for the beaks of the extraction forceps to enter in between the two buccal roots, such as in a maxillary cowhorn ( Figure 11-5 ).

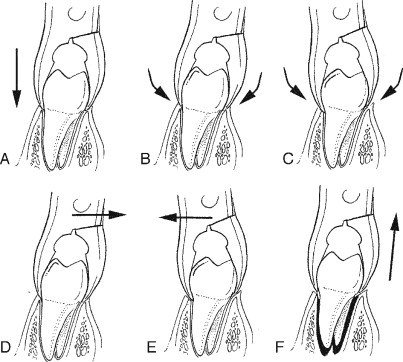

Extraction of lower molars could be the most difficult extraction in the mouth because of the density of the posterior mandible, the root form of lower molars, and proximity to vital anatomic structures. A lower universal forceps #151 is best used. A variety of cowhorn forceps are used to allow for the beaks to seat into the furca with very gentle digital pressure. Once the cowhorn beaks are seated into the furca, gentle proximation of the handles of the forceps takes place. That process will luxate the tooth coronally, and then simple delivery of the tooth will follow. One must still pay great attention to prevent causing any damage to the soft tissue surrounding the extracted tooth ( Figure 11-6 ).

Bone loss after tooth extraction without replacement is a well-documented phenomenon. A skilled surgeon should avoid any traumatic extraction leading to further bone remodeling and ultimately more bone resorption. Should the surgeon expect traumatic extraction, then the patient must be counseled for socket preservation and augmentation by the various grafting techniques available.

▪

SOCKET PRESERVATION AND WOUND CLOSURE

In simple extractions, by definition, no surgical flaps are elevated or required. Thus, simple wound closure is often unnecessary.

Ridge resorption after tooth extraction is a well-documented phenomenon. Secondary to the extraction, the socket will undergo partial bony filling and partial resorption in both the horizontal and vertical dimensions. Extraction sites will undergo about four times faster resorption than the regular biologic rate in the first 12 months. Extraction sites that were restored with removal prostheses will undergo much faster resorption as a result of nonphysiologic compression forces on the alveolar bone surface.

In today’s practice, there is great emphasis on tooth replacement that will meet a higher standard of function and aesthetic outcome. Preserving the extraction sockets and attempting to prevent the collapse of the soft and hard tissue is the best first step toward achieving that goal.

Socket preservation techniques vary depending on the long-term desired treatment plan. The surgeon must be well aware of the various grafting techniques available, the biocompatibility of the grafting material, resorbability, turnover, and handling.

To minimize the resorptive phenomena and accelerate the healing and bone filling process, it is best to isolate the delicate environment inside the socket from the harsh elements in the oral cavity. Grafting the site with the appropriate material and/or using the appropriate membranes will help achieve that goal. Whereas primary closure would be the most desirable environment for appropriate healing in the socket, it does destroy the architecture and the anatomy of the soft tissue in the area and, thus, should be avoided unless absolutely and crucially necessary.

Schlar described a technique of ridge preservation which he termed “The Bio-Col Technique” using a combination of Bio-Oss (Osteohealth Co. Shirley, NY 11967) in the socket and a CollaPlug (SulzerMedica, Carlsbad, CA) wound dressing to cover the Bio-Oss graft. This technique is not only useful in preserving alveolar bone, but in maintaining soft tissue architecture at the extraction site and provides the clinician the benefit of maintaining the esthetic of the area. By immediately supporting the soft tissues surrounding the socket, the restorative dentist will be better able to create a pontic that retains the appearance of a gingival margin and sulcus resulting in a much more esthetic prosthesis.

The surgeon, furthermore, must assess, after the extraction process, the availability of bone volume height and width, especially in an area that would receive an immediate implant or one in the future, or have the pontic of a bridge in a cosmetic zone. A good surgical practice would be to appropriately diagnose and prudently inspect the bony defect before the extraction process and have a prefabricated wax-up to the site that would guide the surgeon to the amount of buildup needed to achieve the desired results.

However, if any papillae or margins were elevated during the simple extraction process to gain access to purchase points or better visibility, then this should be closed with minimal tension, just enough to achieve the required hemostasis and proximation of the anatomic structure to the preextraction conditions. If removable prostheses are used to temporize the site, they should be adjusted to avoid contact with the incision, if possible.

If implants are placed in the extraction socket at the same time, then one should carefully assess the extraction socket margins when placing the implant, accounting for some type of remodeling. If immediate load is not indicated, then one should preferably use a healing abutment on top of the implant that would be flush with the gingival margins and allowed to support the soft tissue architecture. If done correctly, the site will have the best chance of achieving appropriate socket filling around the implant, prevent soft tissue collapse, and avoid any suturing to achieve appropriate hemostasis.

▪

COMPLICATIONS

MILD BLEEDING

Moderate to mild bleeding is normal and expected after extraction. However, it should be self-limited unless a complicating medical history exists. A thorough medical history should always be taken before the extraction to identify medications that could predispose the patient to excessive bleeding, such as blood thinners (Coumadin, aspirin, Lovenox, Plavix, etc.). Patients with bleeding disorders need to be identified before the extraction process and managed accordingly. Management of the medical patient is discussed in a different chapter. However, it is accepted practice for patients on blood thinners to have minor oral surgery procedures without any serious bleeding complications if a coagulation panel is within therapeutic range. Should intraoperative and postoperative bleeding persist, it could be managed easily with local measures, such as direct mild pressure with gauze and/or applying hemostatic mediums (CollaPlug, surgical collatape, surgicoll, etc.) and use of appropriate suturing technique.

▪

LIMITED MOUTH OPENING

If limited mouth opening is one of the postoperative complications, secondary to simple tooth extraction, one must distinguish between exacerbation of prior TMJ preexisting condition versus trauma to the mastication muscles or facial space infections. The most common is traumatic injury secondary to the introduction of the anesthetic through a syringe and its associated needle, causing some degree of muscle tear. The management of these two conditions is distinctly different. An appropriate diagnosis should be made and managed accordingly. Conservative TMJ therapy and physical therapy for simple TMJ versus palliative therapy for muscle tear and patient observation until appropriate healing takes place versus incision and drainage of abscess are appropriate considerations.

▪

DAMAGE TO ADJACENT TEETH

The surgeon must be well aware of the surrounding structures around the surgical field in which he or she is working. Careful assessment must take place before the surgical extraction. A thorough discussion with the patient must take place as well if the potential exists for damaging adjacent teeth, especially those with extensive decay and large restorations. Although this complication is not common with simple tooth extraction, it is sometimes unavoidable.

▪

ORAL ANTRAL COMMUNICATION

In simple extraction of the first and second maxillary molar, it is sometimes common that a communication between the antrum and socket will exist at the extraction site. If the opening is small (less than 2 mm), spontaneous healing will usually take place without any further surgical correction and with the appropriate medical management. If the opening is more than 2 mm, additional suturing and placement of a medium between the oral cavity and the antrum might be necessary. The patients are to be given instructions to avoid any sudden change in the pressure/equilibrium, such as sucking on straws or forceful sneezing.

▪

PAIN MANAGEMENT

Most of the time simple extractions do not necessitate any extensive degree of pain management. Most simple extraction patients would not require any further pain management than over-the-counter medications, such as acetaminophen, ibuprofen, or naproxen sodium. Nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs have proven to be very effective in management of postoperative discomfort following simple tooth extraction, given that the medical history of the patient allows it. If extensive surgical manipulation took place during the process, then one could consider the combination of a narcotic drug along with a nonsteroidal antiinflammatory when necessary.

The patient must be thoroughly instructed as to the side effects of these medications, and the instructions of the administration of the drug should be very carefully reviewed. Nonetheless, whatever management protocol is instituted, the best outcome is always achieved by instructing the patient to start the medications well before the expiration of the local anesthetic effect.

▪

COMPLICATED EXODONTIA

Complicated exodontia involves techniques to remove teeth other than by simple luxation of the tooth and forceps delivery. As all dentists are aware, not all extractions can be done by simply grasping the tooth with forceps and expanding the alveolar bone to deliver the tooth. Conditions, such as advanced caries, abnormal root morphology, or difficult anatomic locations, can make the extraction of a tooth complicated and will necessitate a surgical extraction using specialized techniques.

Experience has taught us that any planned simple extraction can develop complications that will lead to a surgical extraction, and the oral surgeon must therefore be prepared to routinely convert to using the specialized techniques that will be discussed in this section. Although complicated surgical exodontia often emanate from attempts at simple forceps extraction, it is best when surgical extractions are planned. In most cases, proper diagnosis and careful surgical planning before initiation of the procedure will save time, decrease morbidity, and increase efficiency.

INDICATIONS

Common indications for surgical extractions are listed in Box 11-1 .

-

Accidental fracture of the crown during simple extraction that leaves the root buried in the socket

-

Retained roots

-

Severely carious teeth that will fracture with forceps extraction

-

Endodontically treated teeth

-

Teeth with internal resorption

-

Teeth with widely divergent roots

-

Teeth with dilacerated or greatly curved roots

-

Ectopic teeth in positions where forceps cannot be used

-

Teeth that are positioned close to vital anatomic structures

-

Unerupted teeth other than third molars

-

Hypercementosis

-

Ankylosed teeth

-

Mandibular third molar in the proximal segment of a fracture of the mandibular angle region

-

Multirooted teeth located in areas of the jaw where bone preservation is critical for implant placement.

-

Tooth that will be used for autotransplant

▪

GENERAL PRINCIPLES

Surgical extraction, like all other oral and maxillofacial surgery procedures, must adhere to basic surgical principles of careful planning, adequate surgical access and visibility, hemorrhage control, meticulous handling of hard and soft tissues, maintenance of good blood supply to flaps, good instrument mechanics, cleanliness, and painstaking repair of the surgical wound.

Surgical exodontia will usually involve three or more of the following steps:

- 1.

Elevation of a mucoperiosteal flap

- 2.

Ostectomy

- 3.

Sectioning of the tooth

- 4.

Luxation and removal of the roots

- 5.

Removal of radicular pathologic condition when present

- 6.

Débridement of the surgical field and the removal of sharp bony edges

- 7.

Wound closure

As is mandatory for simple extractions, good quality radiographs to visualize decay, root morphology, intrabony pathologic conditions, and approximation to critical anatomic structures are even more critical for surgical extractions. In general the panoramic radiograph is the preferred imaging modality for complex exodontia because it shows the entire teeth-bearing areas, the full extent of any intrabony pathologic conditions that may be present, along with their relationship to vital anatomic structures. When periapical films are used, they should be of good quality and show the entire tooth along with close anatomic structures. For some unerupted teeth, the panoramic film or the sole periapical radiograph will not provide complete or accurate information as to tooth position, and localizing films will be needed to properly determine their position.

▪

FLAP DESIGN

In surgical exodontia, a “full thickness” mucoperiosteal flap will be the type of flap used to facilitate the removal of the desired tooth or root fragment. Reasons for reflecting the flap are to:

- 1.

Allow for complete visualization of the operative field.

- 2.

Prevent unnecessary trauma to the adjacent soft tissue when removing bone or teeth.

- 3.

Provide an adequate working area that will allow for the full removal of intrabony pathologic conditions when present.

Careful consideration must be given to the position of the incisions and to the type and shape of the flap. The following are guidelines for flap design for surgical extractions:

- •

Incisions should be placed over bone not planned for removal.

- •

The incision should be long enough to allow for a flap that will give clear and adequate hard tissue visualization and permit easy retraction without tearing.

- •

The base of the flap should be wider than the reflected free margin to ensure a proper blood supply to the reflected soft tissue.

- •

Avoid placing incisions over vital structures (mental foramen and lingual nerve).

The soft tissue flap configuration can be of three basic designs: the envelope flap, the triangle flap, and the trapezoidal flap.

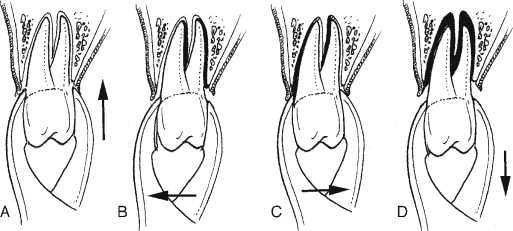

The most common flap used in exodontia is possibly the envelope flap. The incision is made with a #15 blade around the necks of the teeth within the dental sulcus, including the interdental papillae. The length of the incision usually involves three to four teeth, but the length should be that which will provide adequate access to the area of intervention without the need for excessive retraction. Elevation of the flap is started at the sulcular incision, where a sharp periosteal elevator is used to firmly lift the free gingival margins and the incised dental papillae. The periosteum along with the supraperiosteal structures are gently elevated from the bone ( Figure 11-7 ).

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses