5

Applying the Science of Well‐being

By teaching people to tune into their emotions with intelligence and expand their circles of caring, we can transform organizations from the inside out and make a positive difference in our world.

—Daniel Goleman, psychologist, author, and journalist

Emotional intelligence (EI), also known as emotional quotient or EQ, is the ability to monitor our own and others’ feelings and emotions, to discriminate among them, and to use this information to guide our own thinking and actions (Salovey and Mayer 1990). High EI allows us to understand what we and others are feeling, regulate our emotions in positive ways to relieve stress, communicate effectively, empathise with others, and defuse conflict.

The first ‘E’ of the PERLE model spotlights emotional intelligence and its crucial role in building resilience. This is split into three interplaying parts: self-awareness, emotional regulation, and positive emotions. Due to the sheer vastness of this pillar and topic, we explore EI over three chapters.

Tuning to our emotions with intelligence is critical for dental professionals. Our emotions drive our every behaviour. And as the old adage goes in dentistry, patients do not remember what we say but rather how we make them feel. In this chapter, we will explore the transformative benefits of developing EI for dental professionals and how to do so.

EI Benefits in Dentistry

| Benefits of High Emotional Intelligence for Dental Professionals |

|---|

|

Developing high EI has numerous advantages for dental professionals. Self-awareness – that is, knowing how we are feeling – and emotion regulation, the ability to downregulate from stress to calm, helps us build greater resilience and psychological well-being. The ability to manage our emotional life without being hijacked by it is a tremendous learnable skill. With it, we are better equipped to respond well under the pressures of dentistry. High EI leads ultimately to us developing increased empathy with our patients, resulting in better quality of patient care. Recognising emotions in our patients and attempting to understand how they are influencing behaviours is one of the building blocks of empathy. Furthermore, greater connection to patients enhances our levels of engagement at work and hence career satisfaction.

Facets of Emotional Intelligence

Additionally, high EI is essential for effective communication, leadership, and teamwork. Ensuring patients understand the information we are conveying to them is essential for obtaining valid informed consent and for building strong patient relationships that may prevent or reduce the risk of complaints. The ability to recognise by facial expression when a patient is anxious or confused allows a dental professional to pause the consultation and explore any questions or concerns before continuing.

| Guiding Principles of Developing Emotional Intelligence |

|---|

|

What are Emotions?

Emotions are pieces of information that tell us something about how we are experiencing our world. Emotions are often feared and avoided, as they can be painful; however, they are designed to help us survive, relate to other people, communicate how we feel, and respond to our world. Emotions give us feedback on our environment, that is, whether it is dangerous or friendly. They tell us what we need so that we take action to meet our needs. They also are influenced by our thoughts or perceptions and can trigger physical responses and behaviours. All emotions are forms of energy that drive our behaviours. This is explained through the cognitive-behavioural therapy (CBT) model (see Figure 5.1) that conveys the interconnected relationship between our feelings, thoughts, and actions.

Figure 5.1 The CBT model.

Our emotional reaction was learnt from our childhood experiences. If we were predominantly fearful as a child, we may overprotect ourself as an adult, and this may present as anxiety. Emotions are also modified by the genetic makeup of a person (temperament) and the socialisation process.

Taking Off the Mask

With our patient-focused role in dentistry, we need to keep some of our emotions and feelings under the surface and lean into a calm, compassionate, empathetic, and confident state. Although this is of course necessary, it is important, outside our time with patients, to experience our emotions with acceptance and non-judgment and release them. Keeping our feelings bottled up can cause us to blow up or develop stress-related illnesses. Pushing down feelings only means they will resurface at a later date.

Paul Ekman (2003) identified six basic human emotions found across age, gender, and culture, with some emotions arousing you and others calming you down. These include anger, disgust, fear, joy, sadness, and surprise. Our feelings arise from our basic emotions. There are more unpleasant emotions than pleasant. As mentioned in Chapters 1 and 2 (‘the negativity bias’), from an evolutionary standpoint, that makes sense. The benefits of negative emotions elicited by real or potential danger meant that our thought-action repertoire was narrowed, and therefore fear would elicit the action of running away and anger lead to us defending ourselves in battle. Humans also have a tendency towards negative over positive stimuli. For dental professionals, the stimuli that activates our brain to elicit these negative emotions – from a triggering social media post or a crown not seating on a tooth, a difficult extraction, the thought of a difficult RCT, or the worry of an impending exam – is not going to kills us.

The Broadening Effect of Positive Emotions

What do positive emotions do to our thinking? Barbara Fredrickson, leading researcher in positive emotions, has been studying this area with avid interest. Her Broaden and Build Theory (Fredrickson 2001), backed up with research, describes the transformative effects of positive emotions on our success and well-being. The experience of positive emotions, from joy to serenity, gratitude, awe, inspiration, and amusement, opens our minds and broadens our ability to think ‘outside the box’ (Figure 5.2). Our outlook on our environment changes. The world appears larger. We see more possibilities relative to negative or neutral states. This is the opposite case for stress, in which our thinking considerably narrows.

The broadening effect of positive emotions in turn helps us to build personal resources when we need them: intellectual (problem solving, open to learning), physical (cardiovascular health, coordination), social (maintain relationships and create new ones), and psychological (resilience, optimism, sense of identity and goal orientation) (see Figure 5.2). This in turns helps us transform our lives. Interestingly, the impact of positive emotions extends beyond us just feeling better, as they can impact our physical health. Positive emotions can ‘undo cardiovascular after effects of negativity’ (Fredrickson 2009). Positive emotions can help our bodies return to normal physiological functioning significantly faster than other emotions (Fredrickson and Levenson 1998).

| Evidence-Based Benefits of Positive Emotions |

|---|

| Broaden our thinking Build psychological resources Build intellectual resources Build physical resources Build social resources Spiral of further positive emotions More creativity Better academic performance Physicians make better medical decisions (Isen et al. 1991) Look past racial difference and see towards oneness. |

Figure 5.2 The Broaden-and-Build Theory (Fredrickson 2004).

Personality and Emotion

Which personality traits bring us all together? Which traits separate us as individuals? Personality psychology can give us insight into this and acknowledges the individual differences in how we think, feel, and act. The most widely used personality test comes from research by Costa and McRae (1992). They identified five main personality traits across cultures, known as the Big Five. Table 5.1 summarises these traits. How do you think you would score on each trait?

Table 5.1 Big Five trait summaries.

| Extraversion | High scorers: Tend to respond positively to stimuli in the outside world. Feel energised after speaking to a lot of people. Low scorers: Focus inwards, drained after speaking to lots of people, tend to be quieter, shy, and prefer to be alone. |

| Agreeableness | High scorers: Tend to likeable, patient with others, let go of angry feelings quicker, compassionate, and sympathetic to others’ needs. Low scorers: Untrusting, critical, and suspicious. |

| Conscientiousness | High scorers: Pay attention to detail, plan every detail. Tend to have high levels of grit and are diligent, efficient, and reliable. Low scorers: Inattentive, idle, sometimes unreliable. |

| Neuroticism | High scorers: High levels of anxiety, insecurity, tend to experience higher highs and lower lows. Low scorers: Tranquil, steady, and composed. |

| Openness to experience | High scorers: Curious about the world around them and are open to trying new things. Tend to like being creative and exploring alternative ideas. Low scorers: Don’t like to break out of their comfort zone. Tend to be conformist and uncreative. |

EI and Well-being

EI can be thought of as a behaviour and a personality trait. It is impacted by several factors-our personality, attachment style we formed as children, and content and the context of a situation. Higher EI correlates to higher subjective well-being. Our EI does change and adapt over time, perhaps being influenced by the positivity bias as we age. The data suggest that our happiness levels increase as EI increases, such as positively reframing our emotional experiences. High EI is positively related with subjective well-being; mediated by emotional regulation strategies, such as emotional savouring (reliving positive emotions).

The Roadmap to EI

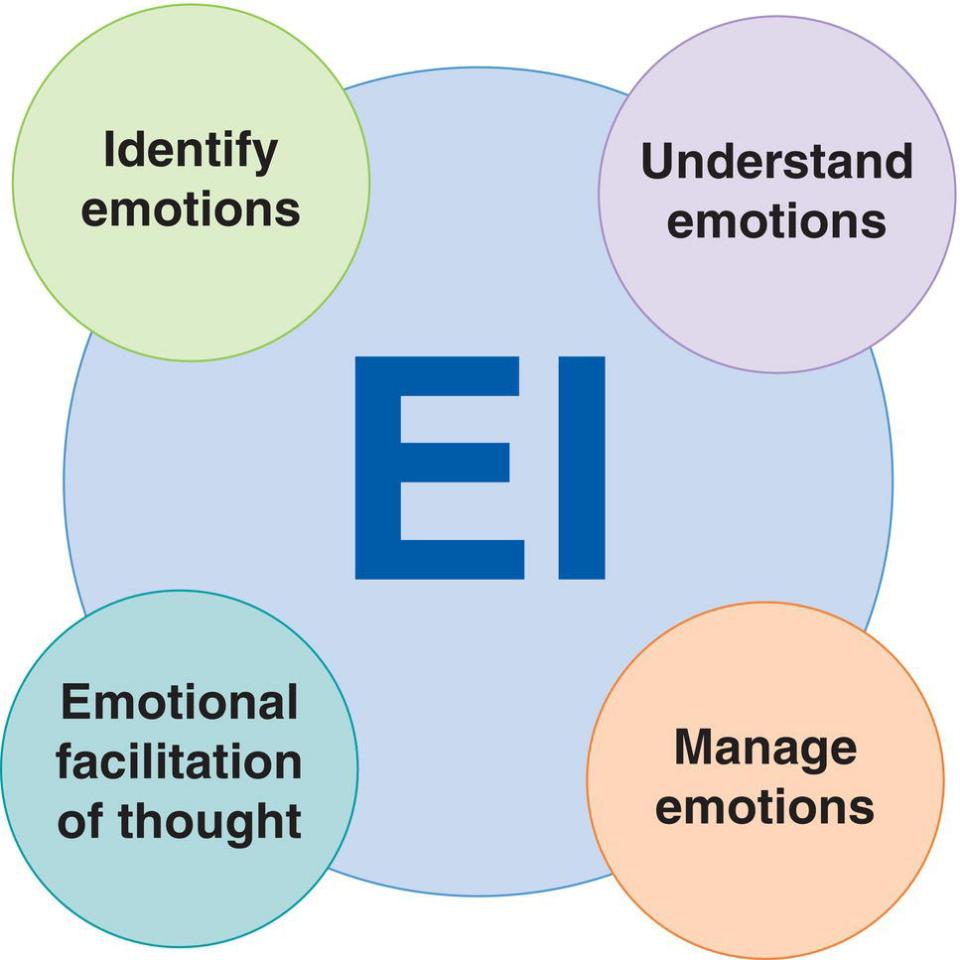

The most supported theory on emotional intelligence comes from the pioneering work of Mayer and Salovey (2007) and their theory on EI. This model considers developing EI as a set of competencies or mental skills that consist of four stages, as shown in Figure 5.3. The stages are summarised below.

| Four stages of EI | Questions to ask yourself to develop mental skills |

|---|---|

| Perceiving: Ability to recognise emotions in yourself and others. Individuals are better equipped for social circumstances. | How do you feel? How do others feel? |

| Using emotions: Use emotions to facilitate mood. | How does your mood influence your thinking? How is it affecting your decision-making? |

| Understanding emotions. | Why are you feeling this? What do these emotions mean? What has triggered this for you? |

| Managing emotions: Manage and self-regulate emotions. | Identify when it’s inappropriate to express certain emotions until the appropriate time |

Figure 5.3 Mayer and Salovey four-branch model of EI (Mayer and Salovey 2007).

We will explore how to regulate difficult emotions and build greater resilience and well-being, using emotional coping tools. Table 5.2 summarises different tools we can select. Some strategies are generally considered to be helpful, such as expressing our feelings, mindfulness, self-compassion, physical exercise, or problem solving, and others mainly unhelpful, for example, alcohol, avoidance, or rumination.

Emotional regulation is the effort to influence which emotions we feel, express, and play out. The key with learning the mind tools to regulate emotions is to understand the range of well-being strategies and experiment with the ones that can help you. This involves reading and understanding the demands of situation and selecting the appropriate emotional regulation skills. Social and cultural contexts also matter. We have to be flexible in the way we use these strategies. Which helpful and unhelpful strategies from Table 5.2 do you already use?

Table 5.2 Tools for regulating emotions.

| Strategy | Helpful? | What is it? | How? | Evidence |

|---|---|---|---|---|

Mindfulness |

|

Paying attention to thoughts and feelings, non-judgmentally. |

|

Galante et al. (2018) – 616 Cambridge University students during exam time. Half had eight-week mindfulness course and the others had normal university support. The mindfulness group had reduced stress during exam period. |

Acceptance |

|

Nonjudgmental acceptance and tolerance of emotions and negative thoughts. Acceptance predicts lower negative emotions and overlaps with mindfulness. |

|

Ford et al. (2017) studied 1000 participants. Individuals who accepted rather than judged their mental experiences and emotions had higher well-being and lower depression and anxiety. |

Self-compassion |

|

Treating yourself with kindness and compassion when stressed or upset (or when you make a mistake). |

|

Leary et al. (2007) found that self-compassion reduced negative emotions after ambivalent feedback and reduced stress, often having a more beneficial effect than self-esteem. |

Expressing your emotions |

|

Telling people how you genuinely feel – your hopes, fears, and challenges. |

|

Mendolia and Kleck (1993) – talking helps you to process your emotions. |

Assertiveness (open communication) |

|

Being clear and open about what you feel and think without blaming or being critical of others. | Be direct, honest, accepting, and responsible about your feelings as opposed to:

|

Sample of over 1000 students, assertiveness linked to greater well-being and less psychological distress. |

Cognitive reappraisal |

|

Generating more helpful interpretations of a situation, for example, thinking of a failure as an opportunity to learn. This is most beneficial where we have limited control or no control, for example, grief/loss. |

|

Gross (1998) – reappraisal decreased emotional arousal in participants. |

Exposure (feel the fear and do it anyway) |

|

Deliberately exposing yourself to feared situation. |

|

Sloan and Telch (2002). |

Physical exercise |

|

Physical exertion that raises your heart rate. |

|

Stathopoulou et al. (2006) – exercise had a beneficial effect on mental health, including reducing depression and anxiety. |

Problem solving |

|

The process of finding solutions to difficult or complex issues. | Use when you are in a stressful situation that is within your control.

|

Cuijpers et al. (2007) – problem solving interventions helped to decrease depression. |

Pleasure and mastery |

|

A technique to help with low mood, pleasure and mastery is a way of planning your day to make sure you include things you find pleasurable and things you find give you a sense of achievement. |

|

Jacobson et al. (1996) – activating pleasure and mastery significantly lowered depression. |

Suppression |

Mainly unhelpful |

Hiding emotional states around others and yourself by pushing away the thoughts and emotions. It may be a short-term helpful strategy but not helpful long term. The opposite of suppression is authenticity – we are comfortable expressing our emotional states. | Use instead. . .

|

Najmi et al. (2014) – OCD sufferers who were asked to suppress their negative OCD thought, actually thought about it more and were more distressed by it than OCD sufferers who were asked to accept their negative thought |

Avoidance |

Mainly unhelpful |

Avoiding situations that lead to negative feelings. This can be a positive short-term strategy where we lack control but poor long-term strategy, as it does not address the causal experience. |

Try. . .

|

Aldao et al. (2010) – avoidance was associated with increases in depression and anxiety. |

Rumination |

Mainly unhelpful |

– ‘Dark’ cousin of acceptance, where we actively focus on negative experiences, fixating and chewing over negatives. Rumination contrasts with savouring, where we relive positive experiences. -For example: ‘Why am I like this, why do I feel so low?, I can’t even get out of bed, I’m really stupid, why can’t I be more like Shabana?, I don’t know why she can do it and I can’t. . .’ |

Try this. . .

|

Nolen-Hoeksema and Morrow (1993) – depressed people who were asked to ruminate became more distressed, but those who were asked to use distraction (thinking about geographical locations) became less depressed. Broderick (2005) replicated Nolen-Hoeksema and Morrow’s (1993) research but with an added mindfulness meditation condition of self- acceptance and awareness of the breath. This worked even better at reducing negative mood. |

Alcohol/drugs |

Mainly unhelpful |

Taking alcohol or other substances to cope with emotions. | The real problem is the medium- and long-term use of drugs for emotion regulation. | Sher and Grekin (2007) – review of the negative effects of alcohol in emotion regulation. |

Self-criticism |

|

Attacking yourself when stressed or having a problem – for example, blaming yourself, or labelling yourself negatively. | For example, telling yourself ‘I’m so lazy, I can’t do anything’, or ‘I’m such an idiot – I really messed that up’ normally has demotivating effects – so it doesn’t help you to ‘work harder’. And it makes you feel worse. Try. . .

|

Gilbert and Procter (2006) – overview of the role of self-criticism in psychological difficulties. |

The Mind Gym fitness menu below is a guide for helpful techniques to manage difficult emotions. Select options from the Mind Gym when you want help in coping with difficult emotions.

Source: Lasse Kristensen / Adobe Stock.

Source: Lasse Kristensen / Adobe Stock.

Lifting the Mask of Self-Doubt: Managing Imposter Syndrome

When did you last hear that voice at the back of your mind tell you are not good enough? That you have managed to fool everyone around you? Imposter syndrome is a set of negative thoughts and beliefs around your capabilities. This can really undermine your resilience and impact career progression. Imposter syndrome can feel like wearing a mask to prevent others finding out your ‘true’ competencies. For some colleagues, the more they accomplish, the more they feel like a fraud. In the short term this may see dental professionals working harder than necessary to make sure that nobody finds out the ‘truth’. Longer term, this self-doubt may cause anxiety or depression.

Imposter syndrome thoughts often impact high-achieving individuals, with a failure to internalise accomplishments and persistent self-doubt or fear of being exposed as a fraud being characteristic. Looking at the media, this type of thinking is often displayed in movies or TV; for example, the character of Betty in Ugly Betty, Andrea in The Devil Wears Prada, Remy in Ratatouille, and Bridget in the Bridget Jones franchise. Just as it is conveyed in the movies, the research shows that imposter syndrome is more common in marginalised groups, such as women and ethnic minorities. Individual factors play a role – such as low self-esteem – as do external factors, such as the toxic environment seen at Runway magazine in The Devil Wears Prada.

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses