9

One-Session Treatment of Dental Phobia

Background

Psychological treatments, i.e. behaviour therapy, for phobias started in the 1960s with British researchers like Gelder and Marks (1966) working with agoraphobia and Americans like Bandura et al. (1969) developing treatments for specific phobias. The first studies on social phobia were published in the 1970s (Argyle et al. 1974). During the 1960s and the 1970s the three main categories of phobias were not differentiated when it came to treatment – all were basically treated in the same format of once a week sessions of one hour for 10–15 sessions or more.

Why develop a one-session treatment (OST)?

In my early clinical work I followed this general format even if I tried to reduce the total number of sessions. One problem that often occurred was return of fear between sessions. If the first session led to a reduction of the patient’s Subjective Unit of Disturbance (SUD) level from say 90 to 60, the second session did not start at a SUD level of 60 but most often at 70–75. Then it went down from there and so on. In an attempt to try to get rid of this return of fear I decided to see if it was possible to carry out the entire treatment in just one session, which was prolonged to a maximum of three hours. The first specific phobia patient I offered to treat this way had spider phobia and the treatment went well, taking 2.5 hours. Instead of publishing this case study I decided to do a case series of 20 consecutive patients in order to have a larger sample for evaluation of the efficacy of the treatment form. It took about seven years to collect these patients since specific phobics rarely apply for treatment. When I then followed them up on average four years after the treatment it turned out that 90 per cent were recovered or much improved after a mean treatment time of 2.1 hours (Öst 1989).

Which specific phobias are suitable for one-session treatment?

Since the first use of OST in 1980 I have used this treatment in about 500 patients in randomized controlled trails (RCTs) on the method and in about the same number of patients in ordinary clinical work. Regarding animal phobias, OST has been used in RCTs for spider and snake phobia and in clinical work for phobia of dogs, cats, rats, birds, wasps, frogs, lizards, worms, ants, insects and hedgehogs. When it comes to other specific phobias RCTs have been carried out on blood, injection, dental, claustro- and flying phobias, whereas it has been used clinically for phobias of deep water, thunderstorms, heights and vomiting. The conclusion is that OST is a suitable treatment for any type of specific phobia as long as it is possible to expose the patient to the anxiety-arousing stimuli.

Acceptability of one-session treatment

In the 13 RCTs on various specific phobias that I have carried out as principal or co-principal investigator a total of 493 patients have been randomized to the OST condition. Of these four (0.8 per cent) have declined participation after being informed about which treatment they would receive. This figure gives what probably is the highest acceptance proportion (99.2 per cent) of any cognitive behavioural treatment. Furthermore, the attrition rate for OST in these studies is zero, which means that every single patient completed the treatment.

Results of one-session treatments

The case series described above gave the necessary clinical and empirical background to start carrying out RCTs on the OST and today there are about 30 RCTs published from researchers in Sweden, Norway, England, Holland, Germany, Austria, USA, Canada and Australia (Öst 2010). A meta-analysis of these studies shows that OST yielded significantly higher effect sizes than wait-list control groups (Hedges’ g = 2.13), than placebo control groups (g = 0.85) and even better than an active treatment (g = 0.81). According to Cohen’s rule of thumb for effect sizes (Cohen 1982) all of these are considered as large since they are above 0.80.

The American Psychological Association’s Task Force (Chambless and Hollon 1998) on empirically supported treatments developed decision criteria. According to these, in order for a treatment to be considered well-established (the highest evidence level) there has to be at least two methodologically rigorous RCTs, performed by different research groups, showing that the treatment in question is significantly better than a placebo control group or another active treatment. The OST fulfils these criteria both regarding OST studies for adult and for children.

The proportion of patients achieving a clinically significant improvement (Jacobson and Truax 1991) varied from 80 per cent for claustro- and injection phobia, to 93 per cent for flying phobia. When the patients were followed-up one year after the treatment the results were either maintained or furthered, with the exception of flying phobia for which deterioration to 64 per cent was observed.

General Description of the One-Session Treatment

The pre-treatment clinical interview

The therapist meets with the patient for a clinical interview, usually one week before the treatment session. There are three purposes to this interview. First, to ascertain that the patient has a specific phobia and that it is not part of agoraphobia where people avoid enclosed spaces as in claustrophobia. Second, to do a brief cognitive behavioural analysis of the patient’s phobia in order to arrive at the maintaining factors. Third, to describe the OST in general terms to the patient.

Diagnostic interview

I usually use the specific phobia section of the Anxiety Disorders Interview Schedule for DSM-IV (ADIS-IV; DiNardo, Brown and Barlow 1994) completed with some additional questions. This takes 30–45 minutes to go through depending on how talkative the patient is and gives a broad picture of the patient’s phobia. It is, of course, possible to use some other semi-structured interview, e.g. the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV (SCID; First et al. 1997) or the M.I.N.I. (Sheehan et al. 1998), which only has questions on the actual diagnostic criteria and gives no surrounding information as the ADIS-IV does.

Brief cognitive behaviour analysis

One important part of the pre-treatment interview is to find out what maintains the individual patient’s phobia. According to the model described by Öst (2012) it is the strong conviction that the catastrophic belief of what an encounter with the phobic situation would lead to that is the important maintaining factor. In order to elicit the patient’s catastrophic belief you should ask him/her to imagine being in the worst phobic situation and not being able to escape from it. Then you get them to describe the worst consequence he/she thinks will occur as a result of the encounter. When the patient has done that you let him/her rate (0–100 per cent) how convinced he/she is that this outcome will occur when being in the phobic situation and having a strong anxiety reaction. Finally, you let the patient rate the conviction when sitting in the therapist’s office talking rationally about his/her phobia. This procedure is illustrated below for a patient with dog phobia.

T: What is the worst thing you fear will happen when you encounter a dog?

P: I don’t know. I’ll scream and run away.

T: Imagine that you cannot leave the situation.

P: I would freeze and just stare at the dog.

T: What do you think that the dog would do?

P: Sooner or later it would run up to me, jump on me and bite me.

T: What would happen with you then?

P: I would die.

T: How would you die?

P: From the shock. My heart would not stand it.

T: OK. The worst that you imagine could happen is that you will die. How convinced are you (0–100 per cent) in the situation, when you are in contact with the dog that it will lead to your death?

P: 100 per cent.

T: And how convinced are you now when you are sitting here talking rationally to me about it?

P: 25 per cent

After having obtained the catastrophic belief I have found it to be a good idea to normalize the patient’s description by saying: ‘Since you believe so strongly in the catastrophe it is logical to avoid/escape the phobic situation. However, this prevents you from obtaining new information that can correct the false belief and, thus, the phobia remains unchanged!’

Description of the OST

The final part of the pre-treatment interview is to describe the OST to the patient. This is done in general terms since you do not want the patient to get hung up on details and not get the big ‘picture’.

First you describe the rationale for the treatment, tailoring the description of the treatment to the individual patient’s problem behaviours. You say that the purpose of the OST is to expose the patient to the phobic situation in a controlled way, enabling him/her to obtain new information that can correct the false catastrophic belief. The reason why control is emphasized is that any anxiety disorder patient will find the situation considerably less anxiety arousing if they experience having control in the situation. However, during the latter part of the OST we purposely insert components of less and less control so that the patient will experience managing that. Furthermore, since the adult patients seen in treatment have had their phobia for 20–30 years on average it might be difficult to understand and encompass that all the treatment it takes is three hours. Thus, you say that the OST should be seen as a start of something that the patient should continue on his/her own afterwards.

Then you highlight the differences between the OST and natural encounters with the phobic object. Natural encounters are unplanned, ungraded, uncontrolled, very brief and usually the patient is alone, whereas the OST is planned, graded, controlled, prolonged and done as a teamwork between patient and therapist.

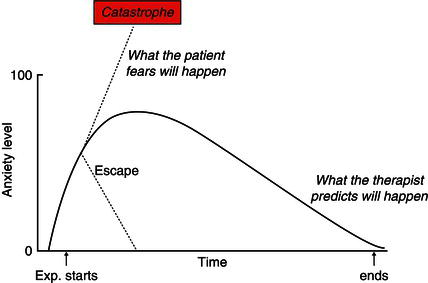

Finally, you draw the anxiety curve (Figure 9.1) to help the patient understand the principles behind the OST. In describing this curve you emphasize that what the patients are doing in natural encounters with the phobic object is to escape, since they strongly believe that remaining in the situation would lead to the catastrophe. By escaping they will experience that the anxiety level is reduced fairly quickly and they will conclude that ‘it was only by escaping that I prevented the catastrophe from happening’. However, the escape also means that the patients will not learn what happens if they remain in the situation, i.e. that the anxiety goes up to 75–80, plateaus there and then goes down providing that the patient remains exposed to the phobic object all the time. In a way the anxiety curve describes two predictions that can be tested in the OST; the patient’s that the catastrophe will occur if he/she stays in the situation and the therapist’s that the anxiety will be reduced and the catastrophe will not happen. At the end of the description of the anxiety curve I also cross out the escape since this prevents the patient from obtaining the information necessary to enable a correction of the catastrophic belief. It is important to get the patient to accept that escape from the phobic situation is not acceptable during the OST. Sometimes you encounter patients who say that the anxiety curve seems logical, but they do not think that it applies to them. This doubt is quite acceptable as long as the patient is prepared to test it out in a real phobic situation. As soon as you get the patient into the phobic situation and stay there he/she will realize that the anxiety curve is a correct picture of what happens in the OST.

Figure 9.1 The anxiety curve

Naturally, patients have to be quite motivated in order to experience rather high levels of anxiety during the OST, with a possible duration of three hours. Usually, I just ask one question to get a good idea of the patient’s motivation for treatment. Before asking the question I tell the patient to think about the answer for a while and not reply immediately. The question is: ‘Is there anything that you are not prepared to do in order to overcome your phobia?’ The most common answer is ‘No’, but sometimes the patient will describe something that reveals a misunderstanding of the OST, giving the therapist the opportunity to clarify these issues. The most peculiar answer I have ever got was from a 30-year-old woman with spider phobia. She thought for about a minute and then said: ‘I am not prepared to divorce my husband’. This clearly indicated that she would do anything that had to do with confronting her phobia.

Pre-treatment instructions

At the very end of the pre-treatment interview I give the patients some instructions which are important for them to understand as they leave the interview. First, the treatment is done as a teamwork. This means that both the patient and the therapist have responsibility for carrying out the OST. The most important instruction is that the therapist will never do anything unplanned in the therapy situation. This means that whatever step in the exposure the therapist wants the patient to take he/she will first describe it verbally, demonstrate it and get the patient’s ‘Yes’ to performing the step in question. If a patient says ‘No’ to a step then the team will have to come up with a step that is easier than the one declined, but still more difficult than the last step completed. This instruction also means that the patient always has the final word about what to do in the OST and the therapist will never force a patient to do anything against his/her will.

Another instruction is that a high level of anxiety is not a goal in itself. I have done OSTs when the patient did not reach a higher SUD level than 40–50, but this does not matter as long as the patient gets the information necessary to correct the catastrophic belief. Finally, I say that the treatment will not break the patient’s ‘personal record’ of anxiety, i.e. the highest anxiety he/she had ever experienced in a phobic situation. This is usually comforting since they survived the worst situation and they will certainly survive the OST as well.

The actual treatment session

The OST can be described as a flexible combination of exposure in vivo and cognitive restructuring with the addition of participant modelling for patients with animal phobia.

Exposure in vivo

The exposure treatment is prolonged (up to three hours) and gradual (a large number of small steps which are gradually more anxiety arousing). Since all the treatment is done in one prolonged session, people sometimes misunderstand and think that it is a flooding type of exposure. This is not the case at all. The OST is done according to an individual anxiety hierarchy. After having completed one step and experienced the anxiety reduction the increase in difficulty to the next step will not be experienced as particularly large.

A prerequisite for the OST is that the patient makes a commitment to remain in the situation until the anxiety fades away. In general terms the patient is encouraged to approach the phobic stimulus to a certain extent (Step 1) and to remain in contact with it until the anxiety has decreased to some extent (20–25 SUD points). Then he/she is instructed to approach further (Step 2) etc. until the entire hierarchy has been worked through. The therapy session is not ended until the anxiety level has been reduced by at least 50 per cent, or completely vanished.

Participant modelling

This treatment method consists of three components: (i) the therapist first demonstrates how to interact with the phobic object; (ii) the therapist then helps the patient gradually to approximate physical contact with the phobic object; and (iii) the patient interacts with the animal on his/her own, only with the help of the therapist’s instructions.

Cognitive restructuring

Whenever there is a good opportunity during the exposure a behavioural test of the patient’s catastrophic cognition, or some part of it, is carried out. Ta/>

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses