9

Minimally Invasive Soft Tissue Grafting

Edward P. Allen and Lewis C. Cummings

Soft tissue grafting is indicated for augmenting sites with deficient-attached gingiva and for covering exposed roots. Surgical grafting techniques have evolved over the past 50 years to a minimally invasive method with refinements in recipient site preparation and the use of allograft donor tissue rather than harvesting tissue from the palate. A distinct advantage when allografts are used is that multiple teeth can be treated in one visit without concern for the amount of palatal tissue available. Regarding recipient site preparation, there has been a progression from open-site preparations to flaps with vertical incisions, to envelope flaps without vertical incisions, to tunnels with only sulcular incisions. There has also been a progression from completely exposed grafts to grafts partially covered by the recipient site flap, to grafts completely covered by coronally positioning the recipient site flap. Increased predictability of root coverage and greater patient comfort paralleled each of these advancements in recipient site design. This chapter will trace the evolution of soft tissue grafting procedures from the free gingival graft (FGG) to the current minimally invasive tunneling technique. The tunneling technique will be described in detail.

Indications for soft tissue grafting

Soft tissue grafting is indicated for augmenting the zone of attached gingiva around teeth and for covering exposed root surfaces. Attached gingiva is that portion of the gingiva that extends coronally from the mucogingival junction (MGJ) to the base of the gingival sulcus. It is comprised of dense collagenous connective tissue that is firmly bound down to the tooth and alveolar bone and provides a protective barrier that is resistant to the physical trauma from normal masticatory function and personal oral hygiene procedures.

A certain amount of attached gingiva is often necessary to maintain health, function, and comfort. The precise amount of attached gingiva needed varies among individuals and physical demands at the site. For example, sites where restorative margins will be placed at the gingival margin and sites where orthodontic or surgical procedures are planned might require augmentation of the attached gingiva due to the added stress of these procedures on the marginal tissue.

The vertical dimension of attached gingiva, commonly called the “width” of attached gingiva, is determined by measuring the depth of the gingival sulcus with a periodontal probe and subtracting this dimension from the vertical measurement of keratinized tissue extending from the MGJ to the mid-facial gingival crest. The thickness of the attached gingiva is also important, but its dimension is typically estimated rather than measured. In sites where there is a deficiency of attached gingiva, inflammation may be persistent, gingival recession may ensue, and the patient may experience discomfort [1]. Sites deemed to have insufficient dimensions of attached gingiva might benefit from grafting for augmentation of the gingival dimensions.

Coverage of exposed roots is another indication for soft tissue grafting, and procedures are now available to both cover roots and augment the zone of attached gingiva at the same time when indicated. Exposed roots present several patient-based problems including esthetics, root sensitivity, and increased susceptibility to cervical lesions. Complete root coverage with increased dimensions of gingiva can routinely be achieved in sites where there is no loss of interdental soft tissue or bone, thus restoring esthetics, function, and comfort [2]. In sites with loss of interdental tissues, partial root coverage can be achieved along with augmentation of gingival dimensions to resist progression of recession.

Early soft tissue grafting techniques termed free gingival grafts (FGGs) were successful in gaining an increased amount of gingiva, popularly called “gain of keratinized tissue,” but required a palatal donor site consisting of both connective tissue and epithelium and were less successful for covering exposed roots. The subepithelial connective tissue graft (CTG) procedure solved the problem of root coverage and used a more comfortable internal harvest method for palatal donor tissue procurement.

The original recipient site preparation method for an FGG required creation of a vascular bed by reflecting and discarding a supraperiosteal tissue flap over the area to be grafted, while a CTG retained the reflected flap and used it to partially cover the graft. Current trends in soft tissue grafting are directed toward more minimally invasive approaches by eliminating vertical incisions and using alternatives to palatal donor tissue, both of which allow a more comfortable post operation course for the patient. The use of the tunneling technique and allograft tissue lead this trend.

Evolution of soft tissue grafting

The FGG, first described in the early 1960s [3,4], provided a means of gaining a zone of attached gingiva in sites demonstrating a gingival deficiency. This procedure was introduced during a time when the gingivectomy was a popular method for eliminating periodontal pockets, and excision of gingiva often resulted in a loss of an adequate protective zone of dense marginal gingiva. It was thought at the time that new gingiva would develop as a response to vigorous tooth brushing. In fact, minimal new marginal keratinized tissue would usually form, being derived from the periodontal ligament. The undesirable consequences of the gingivectomy were recognized and gave rise to flap procedures that preserve existing gingiva. The FGG became a widely used procedure to treat sites with surgically created deficiencies as well as to augment naturally deficient sites.

The FGG requires creation of an open vascular recipient bed and harvesting of a superficial layer of palatal donor tissue approximately 1.0–2.0 mm thick. Both epithelium and connective tissue are harvested. The donor tissue is sutured over the recipient bed, while the palatal donor site is left to heal by secondary intention. The palatal donor site is a source of discomfort and concern for the patient.

While the FGG remains the “gold standard” for gain of keratinized tissue, it was not initially a predictable procedure for coverage of deep, wide root exposure [5]. A modified FGG technique for root coverage was presented in the early 1980s [6,7]. At about the same time, the CTG method was introduced [8,9]. The harvesting of the CT graft from the palate results in an outer flap of epithelium and connective tissue that can be closed primarily, thus reducing discomfort and accelerating healing of the donor site. The CTG method has other advantages over the FGG for root coverage including greater predictability and improved esthetics. The flap created at the recipient site is retained and secured over the graft, thus providing an enhanced blood supply and improving survival of the graft over the avascular root surface. The CTG procedure is now considered to be the “gold standard” for root coverage.

Another popular root coverage technique is the coronally advanced flap (CAF), originally described in the modern era in the mid-1970s [10,11]. The CAF procedure coronally advances existing marginal gingiva to cover exposed roots without the placement of any graft. The advantages of this method include the lack of need for palatal donor tissue and enhanced esthetics. A significant limitation of the CAF is the need for adequate dimensions of gingiva apical to the exposed root surface. It is generally considered necessary to have at least 3.0 mm of gingiva vertically with a thickness of 0.8–1.0 mm to predictably cover roots [12–14].

Originally, the CAF used vertical releasing incisions. In 2000, a novel envelope flap technique with unique papillary incisions and no vertical releasing incisions was introduced [15]. This envelope flap technique has been shown to result in greater probability of complete root coverage, a better postoperative course, and better esthetics compared with a CAF with vertical incisions in the treatment of recession involving multiple adjacent teeth [16].

The CAF is used to cover CTGs where the marginal gingival dimensions are inadequate for CAF alone. As the CTG method has evolved, variations in management of the overlying tissue have been introduced. In the method originally presented by Langer and Langer, vertical incisions were used to facilitate coronal advancement of the overlying flap to partially cover the CTG [9]. Raetzke used a pouch recipient site preparation with no surface incisions but made no attempt to advance the margin coronally to cover the graft over the exposed root surface [8]. This pouch technique was limited to localized recession defects and was more successful in treating shallow recession sites than deep sites. More recently, tunnel procedures have been described for coverage of CTGs [17–20].

The tunnel technique

Currently, root coverage grafting can be accomplished with a minimally invasive tunnel technique using an allograft rather than palatal donor tissue [21,22] (Figure 9.1). Allografts have been shown to result in predictable root coverage and an increase in marginal gingival thickness equivalent to the CTG while reducing the morbidity associated with harvesting of palatal donor tissue [23–27]. A recent long-term randomized clinical trial found stability of root coverage with allografts to be equivalent to that seen with palatal CTG [28]. A distinct advantage when allografts are used is that multiple teeth can be treated in one visit without concern for the amount of palatal tissue available.

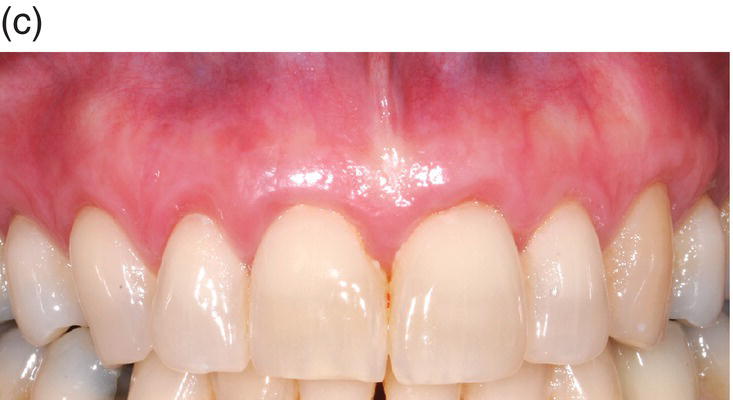

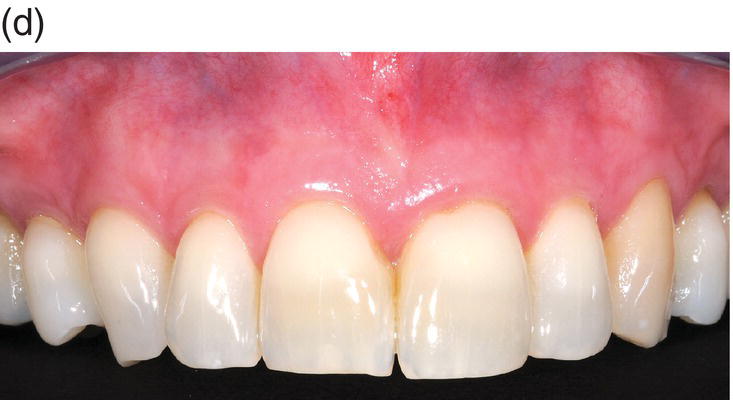

Figure 9.1 (a) Multiple tooth recession and root abrasion in the maxillary arch. (b) A tunnel site preparation has been completed. (c) The allograft on the surface before placement within the pouch. (d) The allograft and pouch were advanced together and secured at the cementoenamel junction with a 6-0 polypropylene continuous sling suture. An additional sling suture was placed around the canine for stabilization. (e) Thick marginal tissue with complete root coverage at 1 year post surgery. The patient elected not to restore the minor cervical enamel defects. (f) Maintenance of root coverage at 2 years post surgery. (g) Esthetically unappealing pretreatment appearance. (h) Improved esthetics at 8 months post surgery.

There are two separate elements to this minimally invasive soft tissue grafting technique:(i) the refined recipient site preparation and (ii) the elimination of the palatal donor site.

Recipient site preparation

The recipient site can be prepared without the need for surface incisions in treatment of most teeth with root exposure. Rather than surface incisions, intrasulcular incisions are made to release the soft tissue attachment to the cervical area of the tooth, and internal supraperiosteal sharp dissection to mobilize the pouch. The intrasulcular incisions extend from the base of the sulcus to the alveolar crest, a distance of approximately 2.0 mm comprised of the epithelial and connective tissue attachments to the root. This soft tissue attachment is often called the “biologic width,” and it may extend more than the usual 2.0 mm where there is a longer connective tissue attachment due to the presence of a bony dehiscence [29]. Through this intrasulcular incision, there is access for dissection of the recipient vascular bed. The dissection extends both apically and laterally both to prepare the recipient vascular bed and to mobilize the pouch sufficiently to allow passive coronal advancement to completely cover the graft. It is necessary to extend the dissection laterally under the papillae adjacent to the treated tooth and additionally to include one tooth on either side of the tooth or teeth with recession. This tunneling under the papillae and lateral extension of the pouch facilitate the passive coronal advancement of the pouch, thus eliminating the need for vertical releasing incisions as well as papillary incisions.

This type of site preparation is ideally suited for treating root exposure in the maxillary arch where the anatomic environment is typically favorable (Figure 9.2). There are few anatomical obstacles to interfere with the dissection process and the quality of the marginal tissue is usually better than that in the mandibular arch.

Figure 9.2 (a) Generalized recession in the maxillary arch with moderately deep cervical defects. (b) Allograft in tunnel over 7 teeth sutured with a 6-0 polypropylene continuous sling suture. An additional sling suture was placed around the left lateral incisor to stabilize the papillae. (c) Complete root coverage and thickened marginal tissue immediately following suture removal at 3 months post surgery. (d) Complete root coverage with a pleasing appearance of the gingiva that shows no evidence of surgical intervention at 2 years post surgery.

Adequate interdental embrasure space is necessary to maintain intact papillae in the tunneling process. Sites with close root approximation are subject to separation of the papillae due to a weak connection between the facial and palatal papillae. This problem is more commonly seen in the mandibular anterior region. In the mandibular arch, caution must be exercised when dissecting near the mental foramen located apical to the second premolar. There are no significant vital structures encountered when dissecting facial to the maxillary teeth.

A shallow vestibule, aberrant frenal attachments, thin tissue, bony undercuts, and an irregular alveolar bony topography represent problems to be managed when performing the tunnel technique. While all of these problems can be overcome, advanced surgical experience is required for successful outcomes, and treatment of sites with these conditions may be best left to periodontists who routinely treat such sites.

Indications for papillary incisions

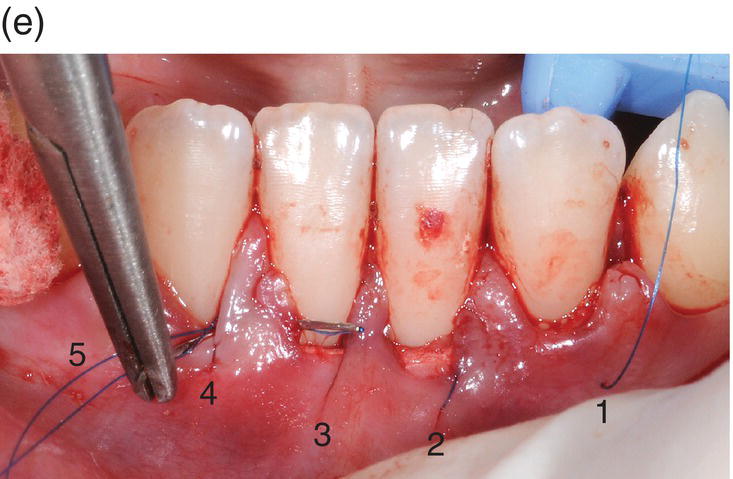

The tunneling technique can be used to augment sites without recession but with minimal attached gingiva, that may be subject to developing recession. These sites include teeth that will have orthodontic treatment or restorations placed at the gingival margin. In sites with very thin tissue and no root exposure, the intrasulcular site preparation method is difficult, especially in the mandibular anterior region where the root width, and thus the sulcular width, is small. In these sites, a papillary releasing incision provides the greater access needed for dissection and graft placement (Figure 9.3). Papillary incisions should be limited to the papilla between the canine and lateral incisor when treating the mandibular anterior region. This will provide access to tunnel under the remaining papillae that will act to prevent apical retraction of the pouch and contribute to wound stability. By retaining all three papillae in the midline, the stress of muscle pull in the midline is distributed to three papillae and the likelihood of a single weak papilla tearing is reduced.

Figure 9.3 (a) Pre-orthodontic 12-year-old female with a shallow vestibule, absence of attached gingiva facial to her mandibular incisors, and thin attached gingiva facial to her lateral incisors. This site will be treated by augmentation grafting to gain a zone of dense connective tissue and deepen the vestibule. (b) A tunnel recipient site was prepared facial to all four incisors with bilateral papillary incisions between the canines and lateral incisors and an allograft was inserted through the right papillary opening. (c) The allograft was passed through the tunnel until reaching the left papillary opening. (d) The coronal border of the allograft was aligned level with the cementoenamel junction in preparation for suturing. (e) A continuous sling suture was initiated at the left open papilla by penetrating both the papilla and graft (1), passing through the distal embrasure and around the lingual aspect of the lateral incisor before returning to the facial through the mesial embrasure. The needle is then passed under the papilla before engaging the pouch and graft at the distal root line angle of the central incisor (2) and passing through the di/>

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses