9 Cysts

ASSUMED KNOWLEDGE

It is assumed that at this stage you will have knowledge/competencies in the following areas:

INTENDED LEARNING OUTCOMES

At the end of this chapter you should be able to:

OVERVIEW

By definition true cysts are developmental or reactive lesions with the vast majority growing by fluid accumulation. This gives them their benign characteristics with the typical resorption of bone and displacement of adjacent structures such as the neurovascular bundle as a result of the pressure effect, properties that are common to benign tumours as well. There are, however, some cysts that grow by cell proliferation, e.g. the odontogenic keratocyst, and they tend to behave in a more aggressive manner with recurrence common. This cyst has been re-classified as a locally invasive tumour (Philipsen 2005), although it should be noted that unlike most tumours, this condition can be successfully treated by partial removal (see below concerning marsupialization). In addition there are tumours, locally invasive and true malignancies, that can appear cystic on presentation, e.g. ameloblastoma, adenoid cystic carcinoma and some sarcomas. Malignant change in cysts has been reported but is a very rare occurrence.

DIAGNOSIS

Presenting symptoms and signs

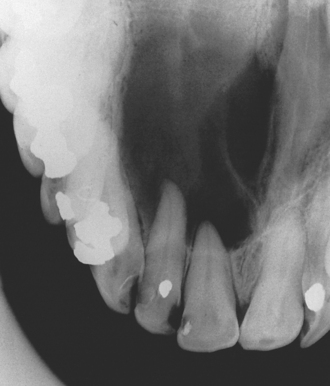

Intrabony cysts may remain symptomless for many years and only come to light as an incidental finding on routine dental inspection or radiographic investigation (Fig. 9.1) or can present in a variety of ways described below.

Association with teeth

Radicular (dental) cysts are the most common of all cysts and are associated with a non-vital root of a tooth. Ectopic teeth can often be associated with cysts either as the primary cause as with the dentigerous cyst (Fig. 9.2) or when displaced by a cyst, such as an odontogenic keratocyst. It is important to appreciate that other more significant conditions, e.g. ameloblastoma, may also present in this manner (see Ch. 8).

Site

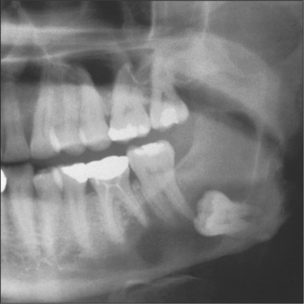

Many cysts show a predilection for specific areas. For example, 75% of odontogenic keratocysts present at the mandibular angle (Fig. 9.3) whilst 88% of glandular odontogenic cysts occur at the anterior mandible (Cawson et al. 2001). Some cysts are completely site-specific such as the nasopalatine duct cyst, which arises from tissues within the incisive canal, and the paradental cyst, which is associated with impacted lower third molars. Also of note is the group of cysts that present in the gingival area including the inflammatory lateral periodontal cyst (a variant of a radicular cyst), the true lateral periodontal cyst, the peripheral odontogenic keratocyst and gingival cyst of adults. These classically present coronal to the apices and in-between teeth in the premolar areas.

Swelling

Swelling is a common presenting complaint and if extensive can cause both intraoral and extraoral asymmetry. Importantly the swelling is normally clinically discrete and well demarcated. Where there has been extensive expansion of the cyst the overlying bone will be thin or absent. In the former, the surface will feel firm but flexible, but if the overlying bone has been completely eroded it will appear as a tense bluish swelling that feels ‘fluctuant’ (Fig. 9.4) (see Ch. 7 for a description of fluctuance).

Patterns of growth and anatomical site

How the cyst grows and the anatomical site will dictate the extent and presentation of swelling. Cysts will expand quicker through cancellous and thin cortical bone and so tend to present sooner in the anterior region than in the posterior mandible. In contrast, the late presentation of cysts in the posterior mandible/maxilla reflects cysts spreading along cancellous bone or into the maxillary air sinus respectively, thus making clinically obvious swelling a late feature. This can be of major significance in terms of making the initial diagnosis, primary management and follow-up, particularly for keratocysts where recurrence is common.

Lobulation

Where a radiolucency displays lobulation it is strongly suggestive of the keratocyst (Fig. 9.3), which has a pattern of cyst growth with ‘invasion’ of lining epithelium through the cancellous bone space leaving behind isthmi of bone.

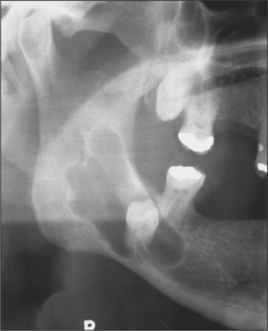

Associated signs/symptoms

As well as eroding bone, cysts can affect the adjacent structures, teeth and neurovascular structures. Erupted teeth are occasionally loosened or displaced, sometimes enough to disrupt the occlusion or alter the shape of the alveolus and the fit of a prosthesis. Rarely cysts can resorb teeth (infection increasing the risk). In extreme cases mandibular cysts can cause so much destruction of bone that a pathological fracture occurs (Fig. 9.5).

Special investigations

Radiology is a key investigation in determining the diagnosis and the extent and anatomical relationships of the lesion. It is therefore important in treatment planning and issues relating to consent. Simple plain films such as orthopantomogram (OPT), periapical and occlusal views are normally sufficient but for extensive cysts, particularly if they may be extending into soft tissue (e.g. the lingual area or the maxillary sinus and pterygoid regions), advanced imaging such as CT will be required. For further details of the radiological features of cysts, readers are referred to standard texts on dental and maxillofacial radiology. However, the general radiological features of cysts can be summarized as radiolucencies with a well-defined, corticated margin. The features of site, shape, relationship to teeth and whether there is any lobulation will all contribute to the diagnosis.

All cyst specimens should therefore be submitted for histological examination (see Ch. 8). Often this takes the form of an excisional biopsy when establishment of the histological diagnosis is coupled with complete removal of the lesion. For larger lesions it is essential to match the cyst type to the appropriate surgical treatment so it is sometimes best to perform an incisional biopsy to establish diagnosis before considering major surgery.

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses