Chapter 9

Communication

Aims

This chapter outlines the key factors that underpin successful communication between patients, parents and members of the dental team, when managing periodontal diseases in children, adolescents and young adults.

Outcome

Having read this chapter the practitioner should have an insight into the development of a child’s skills of reasoning and how this impacts upon communication with the child in a dental setting. The role of the parent or guardian in shaping behaviour and supporting dental health objectives should also be appreciated. The practitioner should be aware of effective methods of verbal and written communication for different age groups and of key messages appropriate for children and adolescents, their parents, and young adults.

Introduction

“You must be able to communicate with people in order to be a good dentist.” This is a statement to which most of us would subscribe; yet there is a tendency to think that the ability to communicate well is a personality trait. Certainly, some people find it easier than others but, nonetheless, communicating skills can be learnt and developed.

In the context of this book, three-way communication between the dentist, patient and parent is essential and is, of course, fundamental to the workings of the whole dental team. When dealing with children, adolescents and young adults effective communication and treatment planning must take into account the patient’s level of development (both mental and physical) and past dental experience. It is not the intention of this chapter to explore stages of development or behavioural management in detail. This is covered in Child Taming: How to Cope with Children in Dental Practice (Chadwick and Hosey, 2003).

Communication with the Young Patient

The Developing Child

When dealing with the child patient it is important to be aware of the child’s capabilities and understanding in order to tailor treatment appropriately.

-

Children under seven years tend to be egocentric in their thinking and unable to grasp another person’s viewpoint.

-

Children under seven years of age may miss many sites in the mouth if brushing unaided and will swallow much of the toothpaste.

-

By age seven, children have the motor skills to brush their teeth reasonably well though parental assistance is still valuable.

-

Children aged seven – 11 can apply reasoning and consider another person’s point of view.

-

Children aged 11 upwards will be able to think in a more abstract way, consider different possibilities for action and weigh up alternatives.

-

Adolescents tend to be influenced by their peer group.

-

Adolescents are not driven by remote goals such as future disease prevention.

Communicating with the Child Patient

When interacting with the child patient it is important that most of the communication is directly with the child – not over their head with the accompanying adult. Care must be taken with choice of language. Jargon should be avoided. As young children do not appreciate the world from anyone else’s viewpoint these explanations should be centred on the child and should be accessible, but without being patronising. It is also important that the practitioner addresses the child directly and makes eye contact, even if further explanations then need to be made to the accompanying adult. The dentist may seem more approachable to the child if he or she makes him/herself accessible by sitting, kneeling or squatting down to meet the child at eye level.

It is important to know how a child likes to be addressed and to record that information for future visits. At the beginning of the visit the initial chat should include non-dental topics and this is the time when the patient’s level of anxiety about the visit can be gauged. A simple explanation of the intentions of that visit should be given with limited detail, since the exact nature of the appointment may not be determined until the examination. It is important to continue to keep in verbal contact with the patient during the examination. A clear end should be made to the visit and a small reward, such as a sticker, can be given to a young child (Fig 9-1).

Fig 9-1 Assorted “reward” stickers.

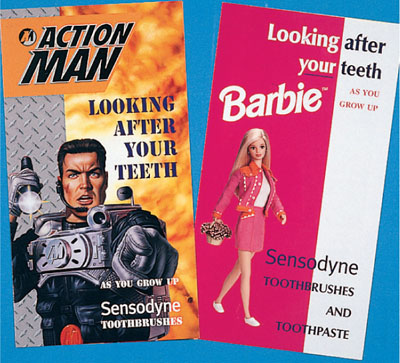

When communicating with a child or adolescent patient it is important to tailor your explanations to the individual. Verbal advice can be supplemented by written advice. Commercially produced leaflets and stickers are available that are specifically targeted at different age groups. These are designed to be visually appealing and often use characters with which the child is familiar (Fig 9-2). Children develop at different rates and may appear more or less mature than their years. As children of seven – 11 years of age can apply reasoning, the clinician may be able to link concepts such as plaque with disease, or brushing with health in this age group. Children older than 11 years of age can compare different options and, therefore, can be significantly involved in planning treatment. Oral hygiene techniques are covered in Chapter 8. However, simple take-home messages on gingivitis and chronic periodontitis for children are shown in Box 9-1. Caries prevention advice should also be given in simple terms.

Fig 9-2 Action ManTM and BarbieTM leaflets for children.

Box 9-1

Information for a Child

Gingivitis

Food and bugs (a mixture called plaque) are sticking to your teeth

Plaque can damage your teeth and is making your gums bleed

Plaque is dirty and can make your mouth smell funny

Brushing your teeth makes your mouth feel clean

Brushing makes your teeth and gums strong

Mum/dad (other) may have to brush the tricky bits in your mouth

The dentist, mum and dad, teachers, etc. will be pleased with you for brushing your teeth

We can tell your gums are well (healthy, strong) when they don’t bleed when you brush your teeth

Chronic Periodontitis

Food and bugs (a mixture called plaque) are sticking to your teeth

Plaque and hard plaque (tartar/calculus) is making your gums bleed

Plaque and hard plaque (tartar/calculus) is slowly damaging the part of the gum that holds your teeth in your mouth

We can mend your gums by getting your mouth clean

You need to clean the soft plaque away every morning and evening

The dentist (hygienist) will clean the hard plaque away

Communicating with Adolescent Patients

Adolescent patients are a difficult group to influence on health matters that will affect them in later life. Since they are not driven by remote goals they do not tend to consider how their current behaviour might pose a threat in the longer term. Explanations of health and disease and its consequences should reflect the motivation of teenagers. As peer group acceptance and appearance are far stronger motivation factors, these can be used to engage the interest of the adolescent patient and make the health message pertinent to them as individuals. Getting across the message that dental disease may cause bad breath or make a person unattractive is likely to be a more powerful influencing factor than the consequences of periodontal disease or caries. A leaflet that asks how kissable the adoles/>

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses