Chapter 8

Principles and Phases of Treatment

Aim

This chapter highlights the principles and phases of periodontal treatment that should be provided for young patients with periodontal diseases.

Outcome

After reading this chapter the practitioner should be aware of how to plan periodontal therapy for the young patient. The reader should have a general understanding of the stages of periodontal treatment (initial, corrective and supportive) and the management of acute periodontal conditions.

Phases of Treatment

When planning periodontal therapy it is useful to consider the management across three phases:

-

initial

-

corrective

-

supportive.

There may be some overlap of procedures and differences in the length of the three phases for different patients and the endpoint of a specific phase of treatment may not always be clear. Nevertheless, such division helps to organise the treatment, to plan what procedures are to be undertaken by which members of the dental team (see Chapter 10) and to avoid missing any key stages of therapy.

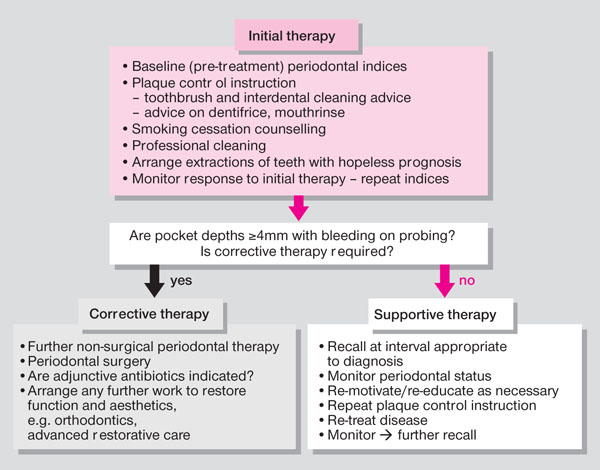

Initial Therapy

This is the first phase in the management and is critical to the success of treatment. It is geared to controlling the primary causative factor in periodontal disease, which is plaque. Even in more complex cases where some of the therapy may be provided by a specialist periodontist this phase of treatment can usually be provided in general dental practice, unless there are medical contraindications. The steps that constitute the initial phase of therapy are shown in Fig 8-1.

Fig 8-1 Components of initial, corrective and supportive phases of periodontal therapy.

Baseline Measurements

The clinician needs to have a record of the extent of disease and the teeth and sites that are affected against which the progress of treatment can be monitored. The Basic Periodontal Examination (BPE) will indicate sextants or index teeth in the mouth where shallow or deep pockets exist. Use of the code * (in addition to the sextant or index tooth score) will flag the presence of furcation defects or clinical attachment loss of 7mm or more. A detailed examination, using appropriate indices (see Chapple and Gilbert 2002), should be done for the following if a BPE score of 4 or * is recorded:

-

probing pocket depths (PPD) (essential)

-

clinical attachment levels (necessary in some cases)

-

bleeding on probing (essential)

-

mobility (essential)

-

furcation involvement (essential)

-

suppuration (essential)

-

recession (necessary in some cases).

A detailed baseline chart should also be considered for BPE score 3 in young patients in whom identification of early disease is crucial but difficult due to the mixed dentition stage delayed gingival retreat, etc. The probing pocket depth and clinical attachment level measures are described in Box 8-1.

Box 8-1

Probing pocket depths

Measured in millimetres with graduated probe

Six sites for each tooth (mesiobuccal, mid-buccal, distobuccal, mesiopalatal, mid-palatal, distopalatal)

Measured from base of pocket to gingival margin

Clinical attachment levels

Measured in millimetres with graduated probe

Six sites for each tooth

Measured from base of pocket to cemento-enamel junction

Although individual probing pocket depths should be recorded for all young patients with evidence of true pocketing from the BPE score, attachment level measurements may not always be made. Attachment levels can be difficult to measure as the position of the cemento-enamel junction (CEJ) is not always easy to detect. However, because the attachment level is measured from a fixed point it can provide the clinician with valuable information on degree of disease which is not dependent on the variable position of the gingival margin. A number of factors can affect the probing pocket depth and attachment level measurements:

-

force applied (ideally 0.20–0.25 N or 20–25g)

-

probe diameter (commonly 0.5mm)

-

inflammation of tissues (the greater the inflammation, the greater the risk of over probing)

-

position of gingival margin (probing pocket depths only)

-

presence of calculus (may block probe advancement)

-

angulation of probe

-

position of probe at gingival margin

-

access

-

crown form

-

patient tolerance

-

visual interpretation and reading of probe gradations by the operator (manual probes only).

The measures and indices for bleeding on probing, furcation involvement, suppuration and recession are shown in Box 8-2.

Box 8-2

Bleeding on probing

Probing performed to base of pocket

Six sites for each tooth (mesiobuccal, mid-buccal, distobuccal, mesiopalatal, mid-palatal, distopalatal)

Presence of bleeding from base of pocket recorded on chart

Mobility

Light force applied with handles of two instruments – do not use finger pressure

Grade I = up to 1mm movement horizontally

Grade II = more than 1mm movement horizontally

Grade III = movement of tooth both horizontally and vertically

Furcation involvement (Fig 8-2)

Probe around multirooted tooth to detect horizontal bone loss between roots

F 1 = horizontal loss of periodontal support not exceeding one-third of the buccolingual width of the tooth

F 2 = horizontal loss of periodontal support exceeding one-third of the width of the tooth, but not encompassing the total width of the furcation area

F 3 = through and through between two roots

Suppuration

Record sites with presence of suppuration on probing

Recession

Measured in millimetres with graduated probe

Measure from apically placed gingival margin to cemento-enamel junction

Record specific sites where recession noted

Fig 8-2 Diagram illustrating the degrees of furcation involvement.

Other Baseline Measurements

Plaque and marginal gingival bleeding

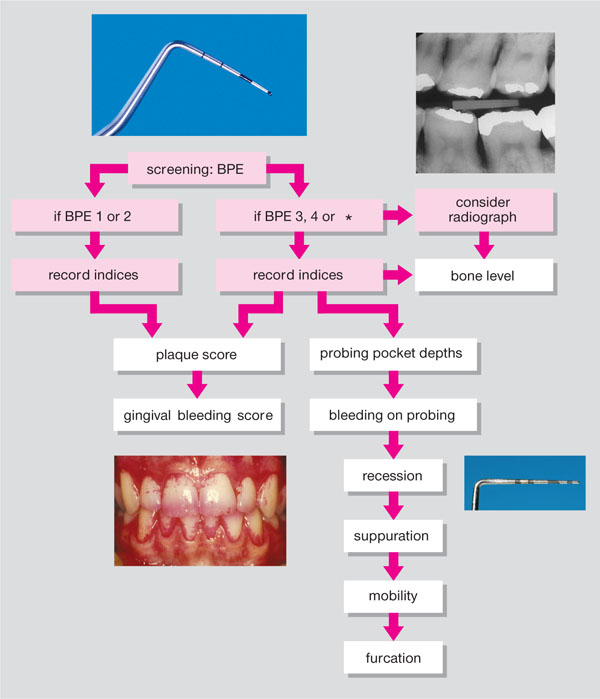

The major aetiological agent in periodontal diseases is plaque and therefore treatment has to be directed at its removal and preventing its re-formation. In view of this, two further types of measure are relevant to the management of young patients with BPE scores of 1 and 2 who have gingivitis, as well as for those showing signs of periodontitis. These are plaque and marginal gingival bleeding scores, which are recorded at baseline to evaluate the level of plaque control the patient has been able to achieve without instruction (Box 8-3). The scores are then repeated as required to monitor the patient’s oral hygiene and motivation. Marginal gingival bleeding scores provide a better measure of longer-term plaque control than plaque scores, because many patients brush immediately prior to dental appointments. Baseline investigations that should be undertaken after a BPE to screen for disease in the young patient are summarised in Fig 8-3.

Box 8-3

Marginal gingival bleeding score

Place periodontal probe in gingival sulcus and run gently around gingival margin

Four sites for each tooth (buccal, mesial, distal, palatal)

Record presence of bleeding from marginal gingival tissues

Calculate number of bleeding sites as a percentage of overall sites (four for each tooth)

Plaque score

Disclose plaque

Four sites for each tooth (buccal, mesial, distal, palatal)

Record presence of plaque at gingival margin (Fig 8-4)

Calculate number of sites with plaque as a percentage of overall sites (Four for each tooth)

By subtracting the percentage of sites with marginal gingival bleeding or plaque from 100% these indices can be converted into marginal gingival bleeding-free scores and plaque-free scores (see section on Motivation).

Fig 8-3 Periodontal indices after Basic Periodontal Examination (BPE) screening.

Fig 8-4 Disclosed plaque.

Patient Plaque Control

Parental assistance

A child under the age of seven does not have the manual dexterity to brush their teeth effectively. Therefore, the parent should be shown how to brush the child’s teeth. As young children can be fiercely independent, it may be that the child is encouraged to start the brushing process and then explain to them that the parent will help “get to the fiddly bits”. The parent should stand behind with the child standing against the parent’s legs (Fig 8-5). The parent can then brush the teeth from behind the child by leaning forwards slightly. Older children can brush their own teeth, however, parental supervision can help to make sure the teeth are brushed for sufficient time and thoroughly.

Fig 8-5 Adult brushing a child’s teeth.

Disclosing agents

Disclosing agents can increase the effectiveness of tooth brushing, in particular, if their use has been demonstrated in the dental surgery (Fig 8-6). Recording a plaque score as part of the baseline measures can illustrate to the child and parent where the plaque is and the degree of brushing required to remove it.

Fig 8-6 Oral health educator demonstrating brushing.

Toothbrushes and brushing techniques

A wide range of toothbrushes is available catering for different ages. The toothbrushes aimed at children and adolescents are usually colourful and may sport popular cartoon characters to make them appealing to the user (Fig 8-7). The scrub tooth brushing technique is effective in children and adolescents; the modified Bass technique can be taught to older children and young adults. Powered toothbrushes are very popular with younger patients. A number of models are specifically targeted at children (Fig 8-8). Those with a rotary head movement are more effective than those with a side-to-side motion. There is evidence that powered toothbrushes may be less abrasive than manual brushes and can be useful for children wearing fixed orthodontic appliances.

Fig 8-7 Manual toothbrushes.

Fig 8-8 Powered toothbrushes.

Interdental cleaning

Periodontal lesions are predominantly interdental. Therefore, interdental cleaning beneath the contact point is important. Use of interdental aids such as floss should be reserved for t/>

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses