8 Oral lesions: differential diagnosis and biopsy techniques

ASSUMED KNOWLEDGE

It is assumed that at this stage you will have knowledge/competencies in the following areas:

INTENDED LEARNING OUTCOMES

At the end of this chapter you should be able to:

OVERVIEW

Many oral lesions are first noticed by the patient or clinician as changes in the colour, texture or disruption of the mucosal surface, or as a swelling or asymmetry of the orofacial structures. When involving or arising from the underlying bone, these lesions may produce a variety of radiological changes, including radiolucencies with or without opacities, evidence of expansion and bone loss in the form of erosion or resorption.

Securing the diagnosis is fundamental to safe and successful management of the patient and will depend on a clear and concise history, careful clinical examination and the use of additional special investigations including radiography, biopsy and other laboratory and diagnostic techniques. Within this spectrum, biopsy is a commonly performed test and is detailed later in this chapter. Should the lesion appear malignant, biopsy should not be performed in general practice, but the patient should be referred immediately for a specialist opinion (see Ch. 10). This approach avoids the need for the general practitioner to break unexpected/distressing news with the consequent requirement to explore the management options with a now anxious patient.

SOFT-TISSUE LESIONS

Diagnosis

Soft-tissue oral lesions are common, often symptomless, slow-growing lumps and are first noticed by the clinician at a routine examination so the clinical history might not contribute greatly to making the diagnosis. Pain is unusual and would indicate infection in a lesion such as a cyst (secondary infection, see Ch. 9). On rare occasions it may indicate aggressive behaviour, e.g. malignant tumour of minor salivary gland (Ch. 14).

Colour

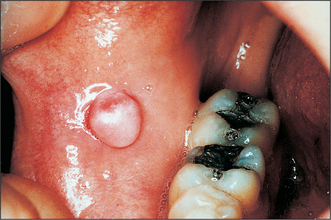

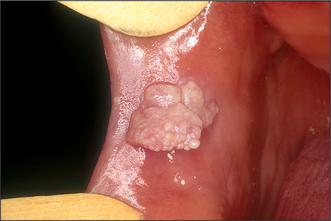

Colour will distinguish between fibroepithelial polyps (pink) (Fig. 8.1) and the white rough cauliflower presentation of viral papillomas (warts) (Fig. 8.2). Mucous cysts tend to be translucent with a bluish colour (see Figs 14.7, 14.8) and haemangiomas and ‘venous lakes’ (Fig. 8.3) dark blue. Pyogenic granulomas (Fig. 8.4) and giant-cell epulides (Fig. 8.5) normally present as maroon/red.

Anatomical relationships and consistency

Lesions may also be distinguished by their depth within the oral tissues and their relationship to adjacent structures. This will differentiate superficial lesions such as fibroepithelial polyps, viral papillomas and epulides (gingival swellings) from submucosal lesions. Palpation is essential to define the lesion’s consistency and distinguish between discrete and diffuse swellings, or whether the lesion is mobile or attached to deeper structures. Solid submucosal lesions can be reactive (e.g. lymph nodes) or neoplastic arising from any of the submucosal structures (e.g. adenomata of minor salivary glands and neurilemmomas). All submucosal swellings that are solid have the potential to be neoplastic and must be investigated.

Modifying influences

The intraoral environment having given rise to lesions may in turn alter their morphology, depending on site. For example, fibroepithelial polyps can vary in presentation from ‘leaf fibromas’ in the palate to denture-induced hyperplasia at the periphery of a denture (see Figs 11.5, 11.6). Immature or developing polyps, particularly when arising from the gingivae, are described as pyogenic granulomas and the pregnancy epulis is a variant. They present as red, acutely inflamed lesions that are soft and bleed readily. Similar in presentation is the peripheral giant-cell granuloma although this may be more purple.

White/red and pigmented lesions

White and red patches are discussed in detail in Chapter 10 (see Figs 10.1, 10.2), but it should be noted that a wide array of white patches that have no significant malignant potential can occur. The difficulty is that interpretation of this risk almost always requires a histological diagnosis. Biopsy is therefore mandatory for all unexplained lesions and the decision not to biopsy requires clinical experience in the management of these types of lesions.

TREATMENT OF SOFT-TISSUE LESIONS

Fibroepithelial polyps, squamous papillomas and epulides

Surgical management of denture-induced hyperplasia must be combined with appropriate modification to the prosthesis such as temporary relining (Ch. 11). This is essential to retain sulcus form and prevent recurrence and is similarly so for ‘leaf-fibroma’ in the palate. Denture-induced hyperplasia can be extensive and, when affecting the lower jaw, is often related to other significant anatomical structures. This is particularly so in the anterior region where the main trunk of the mental nerve can be superficial due to resorption of the alveolus. The lingual nerve can also be at risk when the lingual side is operated on. In these circumstances it is important to carefully identify the edge of the hyperplastic tissue, to keep the excision superficial and to use blunt dissection to free the tissue from underlying structures (see section on biopsy).

Mucous cysts

Mucous cysts divide between the common extravasation cyst and the rarer retention cyst and present as tense bluish swellings often in the lower lip (see Fig. 14.7). These conditions are discussed in Chapter 14.

Vascular lesions

Vascular lesions are best considered as two groups: the rare haemangiomas, which can be extensive and multiple, and the common smaller degenerative malformations (varicosities) often seen on the lip in older patients (Fig. 8.3). For the former it is essential that the type, site and extent are fully evaluated, which normally requires referral to a specialist centre. For extensive and deep lesions or where there is any possibility that the haemangioma extends into bone, extractions or other surgery must be avoided until the type and extent of the vascular abnormality have been established. Conversely, discrete small lesions are easily dealt with either by excision with appropriate management of the vascular source or by cryotherapy. Indications for surgery are cosmetic or lesions that are repeatedly traumatized and bleed.

DIAGNOSIS AND TREATMENT OF HARD-TISSUE LESIONS

Overview

Hard-tissue lesions can arise from odontogenic tissue or from bone. They present a range of diagnoses from developmental lesions such as palatal or mandibular tori or odontomas (see Figs 8.6, 11.13, 11.14) and bony exostoses, to the rarer benign and locally invasive lesions such as ossifying fibroma, ameloblastoma and cementoblastoma.

Often they first come to attention as a bone-hard swelling beneath the overlying mucosa, but in many cases presentation is an incidental finding on routine radiography. As the symptoms and signs have so much overlap, diagnosis is largely dependent on radiological findings and, more importantly, histology. As described below, site can be an important sign in establishing the diagnosis: not only are the lesions within this group difficult to separate, they are often clinically and radiographically similar to cysts (see Ch. 9). As with soft-tissue lesions, there will be malignant counterparts, e.g. osteosarc/>

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses