Oral and maxillofacial injuries

8.1 Assessment of the injured patient

Primary survey

• Airway maintenance with cervical spine control.

• Circulation with control of haemorrhage.

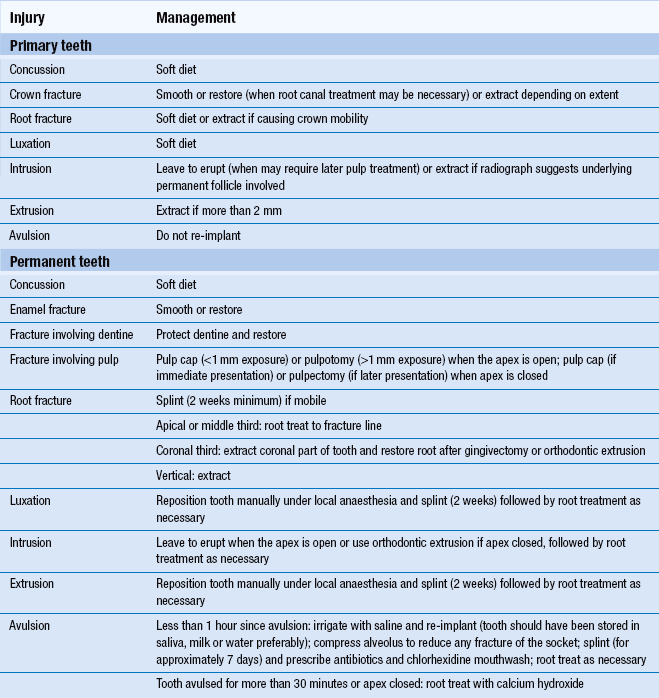

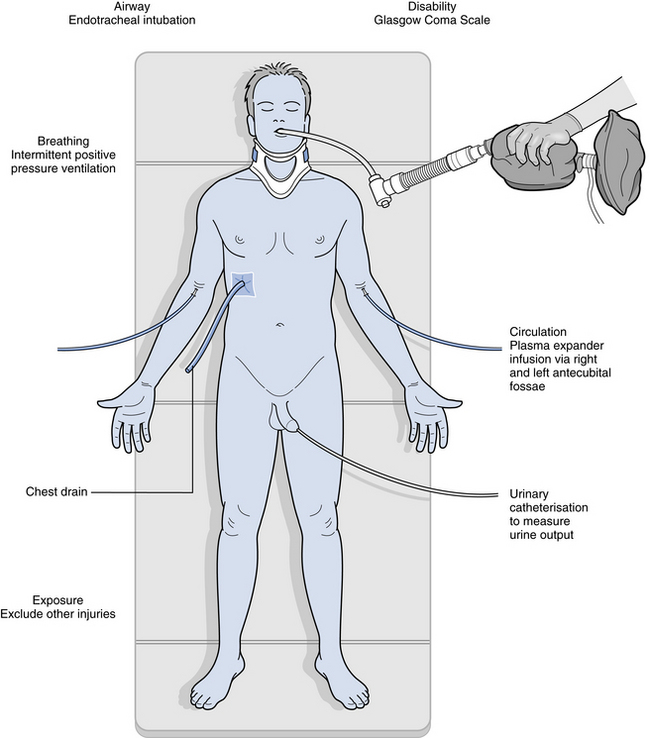

These are illustrated in Fig. 8.1. Universal precautions of cross-infection control are adopted.

Fig. 8.1 Trauma management primary survey.

Airway

Airway management skills are necessary because the trauma patient will not be able to maintain his or her own airway if unconscious or if the airway is compromised by serious facial soft tissue injury or facial fractures. However, airway skills are also important in other situations, such as when consciousness is altered by alcohol or other drugs, or when patients are treated with sedation and general anaesthesia. It is important to understand:

• how to recognise airway obstruction

• how to clear and maintain the airway with basic skills

• the role of advanced airway management including surgical management.

Airway obstruction may be recognised by the ‘look, listen and feel’ observations for breathing. Common causes of upper airway obstruction are the tongue and other soft tissues, blood, vomit, foreign body or oedema. Obstruction may be partial or complete:

• silence suggests complete obstruction

• gurgling suggests presence of liquid

• snoring arises when the pharynx is partially occluded by the tongue or soft palate

Correction of airway obstruction is as described in Chapter 3 with the basic manoeuvre of chin lift or jaw thrust, use of oropharyngeal or nasopharyngeal airways and suction. The jaw thrust is the method of choice for the trauma victim as this avoids extension of a potentially injured neck, and the nasopharyngeal airway should be avoided if a fracture of the maxilla is suspected as it may pass into the cranial fossa. Airway compromise resulting from facial injury will require the early involvement of the oral and maxillofacial surgeon. Advanced airway management by way of endotracheal intubation is the ‘gold standard’ of airway maintenance and protection but is only carried out in the trauma situation after cervical spine radiograph has excluded bony injury.

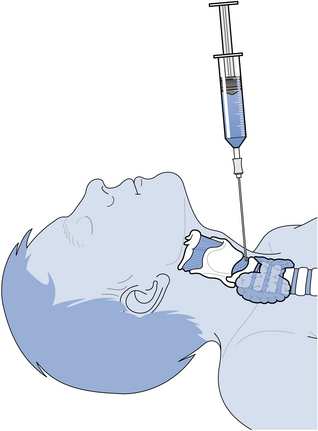

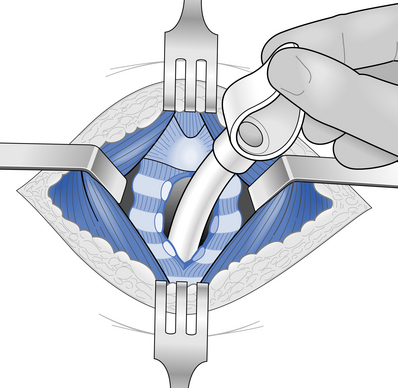

Surgical airway intervention may be indicated, as a life-saving procedure, if it is not possible to intubate the trachea. This may consist of a needle cricothyroidotomy, in which a large-calibre plastic cannula is inserted into the trachea through the cricothyroid membrane (Fig. 8.2). Alternatively, a surgical cricothyroidotomy may be undertaken with a transverse incision through the membrane to permit placement of a small endotracheal tube. These measures can provide up to 45 minutes of extra time in which to arrange undertaking an emergency tracheostomy in a theatre environment. A transverse skin incision is made midway between the cricoid cartilage and the suprasternal notch followed by midline dissection of the infrahyoid muscles and division of the thyroid isthmus. Haemostasis is achieved and then the trachea is opened by cutting away part of the second and third rings to create a circular opening so that a tracheostomy tube may be placed and secured (Fig. 8.3).

Fig. 8.2 Needle cricothyroidotomy.

Fig. 8.3 Insertion of tracheostomy tube.

Breathing

Once an airway has been established, then the adequacy of ventilation must be assessed. Artificial ventilation must be commenced immediately when spontaneous ventilation is inadequate or absent using a self-inflating bag and mask with attached oxygen (see Chapter 3). Serious chest injuries such as tension pneumothorax and cardiac tamponade will compromise spontaneous ventilation. Early diagnosis of these potentially life-threatening conditions is essential so that they can be managed and permit adequate ventilation of the patient. An orogastric rather than nasogastric tube is placed when there is suspicion of base of skull fracture to decompress the stomach. A pulse oximeter monitors atrial oxygen saturation.

Circulation

Intravenous fluids should be infused via a large peripheral vein such as in the antecubital fossa. When there is a need to maintain blood pressure, plasma expanders such as Gelofusine or Haemaccel are better than crystalloids, such as sodium chloride, as they remain in the vascular compartment for longer. Urinary catheterisation is required and adequate fluid replacement is monitored by documenting urine output, peripheral perfusion and temperature. The prognosis is better when the patient is warm with full veins and a good urine output. Electorcardiographic (ECG) monitoring is undertaken.

Secondary survey

A secondary survey is carried out once the patient’s general condition has been stabilised. This consists of a top-to-toe detailed patient examination of all body systems and a more thorough neurological examination, including testing of the cranial nerves. The particular role of the oral and maxillofacial surgeon in the secondary survey is to carry out a detailed examination of the head, neck and orofacial region. Appropriate radiographs or other investigations such as computed tomography (CT) can then be arranged and definitive care planned.

Children

8.2 Dental injuries

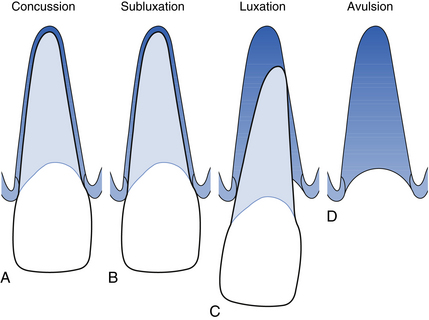

Definitions of a few basic terms are useful (Fig. 8.4).

Fig. 8.4 Examples of some dental injuries.

Concussion: A traumatic event leads to damage to the periodontium without loosening or displacement of the tooth.

8.3 Facial soft tissue injuries

Surgical management of lacerations

Small lacerations can usually be sutured under local anaesthesia unless the patient is a young child, in which case general anaesthesia is indicated. Thorough cleaning is necessary before wound closure. Skin lacerations are closed with absorbable material such as polyglactin (Vicryl) placed deep if necessary and then the overlying skin closed with fine non-absorbable material such as 6/0 Prolene or Ethilon. Intraoral wounds may be closed with Vicryl or silk. It is important when repairing a lip laceration which involves the vermilion border that it is accurately lined up to avoid an ugly step on healing.

8.4 Facial fractures

Clinical presentation

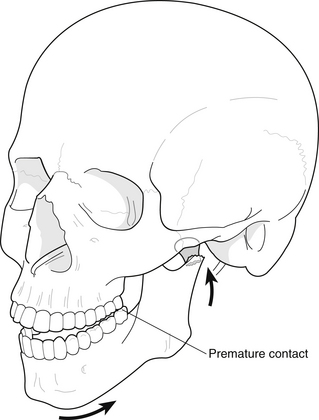

Examination consists of the palpation of bony margins of the facial skeleton starting with the supraorbital rims and progressing down to the lower border of the mandible, comparing right and left sides. The eyes are examined for double vision (diplopia), any restriction of movement and subconjunctival haemorrhage. The condyles of the mandible are palpated and movements of the mandible checked. Swelling, bruising and lacerations are noted together with any areas of altered sensation that may have resulted because of damage to branches of the trigeminal nerve. Any evidence of cerebrospinal fluid leaking from the nose or ears is noted, as this is an important feature of a fracture of the base of the skull. An intraoral examination is then carried out, looking particularly for alterations to the occlusion (Fig. 8.5), a step in the occlusion (Fig. 8.6), fractured or displaced teeth, lacerations and bruises. The stability of the maxilla is checked by bimanual palpation, one hand attempting to mobilise the maxilla by grasping it from an intraoral approach, and the other noting any movement at extraoral sites such as nasal, zygomatic-frontal and infraorbital. Features that suggest the fracture of a particular part of the facial skeleton are:

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses