Chapter 8

Disorders of Salivary Glands and Salivation

Aim

The aim of this chapter is to describe the various disorders that can affect the salivary glands and salivation.

Outcome

After reading this chapter you should have an understanding of the various disorders that can affect the salivary glands and salivation, their investigation and management.

Introduction

Disorders of salivary glands and salivation are relatively common and for the purpose of this chapter are classified into the following categories:

-

salivary flow disturbance

-

salivary gland infections

-

salivary gland swellings.

Salivary Flow Disturbance

The lining of the mouth is kept moist by saliva, a complex fluid that helps keep it in a healthy state. The body produces approximately 1.5 litres of saliva per day with resting flow rates undergoing a circadian rhythm fluctuation that is constant from day to day. The resting flow rate is at its lowest during the night. Thus patients with low levels of saliva experience their worst symptoms during this time. Salivary flow can be stimulated by chewing or by the thought or smell of food. It can be diminished by emotions such as anxiety.

Sources of Saliva

Full saliva is produced by the salivary glands, both major and minor. The major salivary glands are the paired parotid, submandibular and sublingual glands. Congenital absence of one or more of these glands can occur but is rare. The minor salivary glands are numerous and scattered around the mouth but predominantly around the lips and the junction of the hard and soft palate.

Composition and Functions of Saliva

Analysis of the components of saliva presents many difficulties. Its composition varies from person to person and at different times in one individual. The relative amounts of each component differ depending on the relative contribution from each source. This, in turn, is dependent on the stimulus and circumstances at the time. In general, the parotids produce watery or serous saliva while the sublingual and minor glands produce thicker and more viscous (mucous) saliva. The submandibular glands produce combinations of both. Details of the exact composition of saliva are outwith the scope of this book and the reader is recommended to seek further details in a standard text on oral biology. The chief functions of saliva are:

-

mucosal protection – lubrication and tissue repair

-

microbial control – bacteria, fungi and some viruses

-

alimentation – gustation, bolus formation and translocation

-

digestion – especially in the initiation of complex carbohydrate breakdown

-

remineralisation of teeth – through presence of calcium and phosphate

-

buffering – pH maintenance.

It can be seen from the above list that changes in either the quantity or composition of saliva can have a significant effect on the health of the oral tissues.

Measurement of Salivary Flow (Sialometry)

Measurement of salivary flow rates may be useful in assessing the severity of disease in the glands. Full saliva can be collected by allowing it to drain into a collecting cup over a period of time, usually over a 15-minute period (normal >1.5ml), ensuring that no swallowing occurs. The difficulty with the method is preventing mechanical stimulation. In addition, drawing attention to salivation may in itself cause stimulation. It is possible to measure stimulated salivary flow by getting the patient to chew on an inert substance, such as gum or a rubber band, then getting them to spit into a pot again over a period of time, usually five minutes, then measuring or weighing the quantity produced. To measure the flow rate of individual major glands, cannulation of the salivary duct or the use of small collecting chambers that fit over the duct opening may be used.

‘The Dry Mouth’ (Xerostomia)

The complaint of having a dry mouth is common and can arise from either a change in sensation or reduction in the amount of saliva produced (Fig 8-1). As with all conditions, it is essential to take a thorough history of the complaint and any associated features. The history should include details of a patient’s smoking habits and alcohol consumption. The former can have a drying effect on oral tissues and the latter may cause dehydration. Patients with a reduced quantity of saliva will almost invariably indicate that their symptoms are worse at night. They complain of waking frequently and having to have sips of water to try and relubricate their oral tissues. In addition to their dryness they may also indicate problems with swallowing. They may have adapted their diet accordingly, avoiding dry foods and having to drink fluid in order to swallow. They may also state that food has lost its taste. It is often these latter features that patients find most distressing.

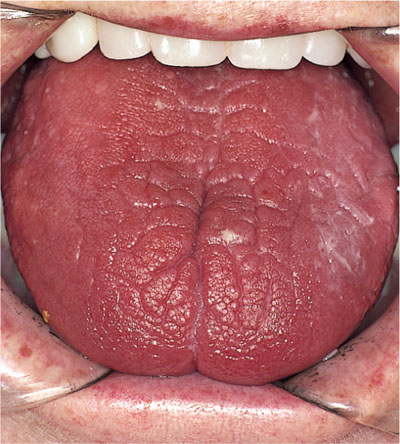

Clinical examination of a patient with dry mouth follows the same pattern as for those with other conditions, although certain signs may be apparent. On giving their history it may be noticed that the speech has a clicking quality as a result of the tongue sticking to the palatal mucosa. The oral tissues will appear dry and somewhat atrophic, this being most apparent on the tongue, which frequently becomes depapilated with a lobulated surface.

In severe cases of dry mouth only scant (or no) saliva will be expressible from the main ducts. This can sometimes happen in the otherwise healthy patient as a result of anxiety, but simple stimulation through the application of a drop of lemon juice to the mouth should differentiate a temporary from a more permanent problem.

Causes for Dry Mouth

A number of conditions can cause xerostomia. These are discussed below.

Sjögren’s Syndrome (Figs 8-1 and 8-2)

The combination of dryness of the eyes (xerophthalmia) and mouth (xerostomia) due to an autoimmune, chronic inflammatory damage to the lacrimal and salivary glands was first described by Sjögren in the 1930s. When these two features appear alone the condition is referred to as primary Sjögren’s syndrome, when associated with various connective tissue disorders – such as rheumatoid arthritis, systemic lupus erythematosis, systemic sclerosis, CREST syndrome and primary biliary cirrhosis – it is known as secondary Sjögren’s syndrome. It is estimated that around 15% of patients with rheumatoid arthritis will also have symptoms of dry eyes and dry mouth.

Like with many other autoimmune conditions there is a tendency for females to be affected more than males. In some instances the condition is familial. Its onset is insidious and consequently tends to present over the age of 30.

Although regarded as principally involving the eyes and mouth, the condition can also be associated with a variety of other effects, such as a dry vagina, irritable bowel-type symptoms and other manifestations. Patients (and occasionally their medical advisers) may be unaware of the connection. The term Sicca syndrome was previously used as an alternative name for primary Sjögren’s syndrome, although more recently it has been suggested that this term be used only for those who, despite their symptoms, have a negative labial gland biopsy (see below).

Fig 8-1 Severe xerostomia. Note how the lingual mucosa has become atrophic and fissured. This patient has Sjögren’s syndrome

Fig 8-2 Conjunctivitis as a result of dry eyes (xerophthalmia) in a patient with Sjögren’s syndrome. By permission of Oxford University Press from “Oral Pathology 4/e” edited by Soames, JV & Southam, JC (2005).

Pathogensis

Viral, genetic and immune factors are thought to be involved in the pathogensis of Sjögren’s syndrome. Ro and La extractable antinuclear antibodies (ENA) are found in approximately 80% and 50% respectively of cases, particularly with primary Sjögren’s syndrome.

Histologically the salivary glands are infiltrated by lymphocytes, resulting in acinar destruction with fibrosis and myoepithelial cell proliferation, which may form ‘islands’ and ductal damage. The identification of foci of lymphocytes forms the basis of diagnosis from the labial gland biopsy (see below). The lymphocyte infiltration may become gross, resulting in gland enlargement forming a pseudolymphoma. In some cases a malignant B-cell lymphoma may develop, with resultant rapid enlargement of the affected gland.

Diagnosis

A number of diagnostic tests may be used. These include:

-

Labial gland biopsy – regarded as the ‘gold standard’ diagnostic test for Sjögren’s syndrome. Between five to seven minor labial glands are removed through a vertical incision in the lower lip adjacent to the canine. Histological confirmation involves finding several foci of lymphocytic infiltration.

-

Salivary flow measures (sialometry) – these tests are somewhat unreliable and time-consuming to perform and consequently are not always undertaken routinely. They can be useful, however, in reassuring patients who have otherwise normal flow levels.

-

Tear secretion (Schirmer test) – placement of strip of filter paper under the lower eyelid and left with the eyes closed for five minutes. Wetting of the filter paper 5mm or less after this period is considered positive.

-

Autoantibodies – autoantibodies associated with the various connective tissue disorders should be investigated, including rheumatoid factor, anti-nuclear factor and antimitrochondrial antibodies. Specific ENA antibodies, such as anti Ro and La, are present in a significant proportion of patients with Sjögren’s syndrome.

-

Nuclear medicine studies – reduced uptake of technetium by salivary glands. This investigation is relatively non-specific but does give an overview of gland activity.

-

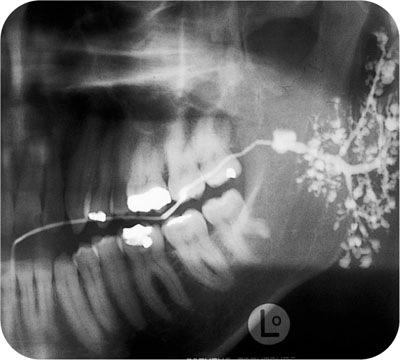

Sialography – classically shows a ‘snow storm’ or ‘cherry blossom’ appearance due to sialectasia (Fig 8-3).

Fig 8-3 Punctate and globular sialectasia demonstrated on left parotid sialogram in a patient with Sjögren’s syndrome.

An oral rinse or mucosal smear should be taken to investigate the presence of Candida if there is any soreness.

Management

Currently it is not possible to control the underlying autoimmune disease in Sjögren’s syndrome. Patients do require careful follow-up, however, because of the implications of having a dry mouth. Problems include increased caries rate, particularly of the incisal edges and smooth surfaces, increased susceptibility to periodontal disease and increased liability to oral infections, particularly candidiasis. In addition the possibility of development of lymphoma needs to be considered. Patients who have significant problems from their dry eyes should be advised to see an ophthalmologist because of the risk of conjunctivitis, corneal damage and resultant blindness. Dry eyes are usually managed with artificial tears (hypomellose eye drops) or on occasions by the temporary or permanent obliteration of the tear duct, reducing the drainage of the small quantity of tears that may be secreted.

Management of Oral Problems

It is wise to advise patients to avoid things that may exacerbate their xerostomia – for example, drugs with a sympathomimetic effect, alcohol, smoking and dry foods such as biscuits.

Artificial Salivary Substitutes and Stimulants

A whole range of artificial saliva preparations is available, mostly based on either carboxymethylcellulose (for example, Glandosane) or mucin (for example, Saliva Orthana). The former products may have a low pH that could damage teeth and should be avoided in dentate patients. Preferably products with a more neutral pH containing fluoride should be selected. Recently oral hygiene products (toothpaste and mouthwash) have been developed to use in conjunction/>

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses