Chapter 7

Trauma to the Teeth and Jaws

Aim

This chapter provides an overview of traumatic injuries to the dentition and jaws and covers the types of injuries that are likely to present to the dental practitioner.

Introduction

The teeth and jaws are frequently subject to traumatic forces that may be accidental (e.g. road traffic accident or sporting injury) or non accidental (e.g. assault). In all cases of trauma, the patient must undergo a clinical examination to determine the type and extent of the injuries sustained. The clinical examination should be undertaken methodically and thoroughly, remembering to examine the soft tissues as well as the teeth and jaws for damage.

The nature and magnitude of the injury will determine whether a radiographic assessment is required and what radiographs are most appropriate. In those instances when the clinical examination is difficult (e.g. the patient is uncooperative or in extreme discomfort), sufficient information may be obtained from the history and an initial clinical inspection to allow a radiographic examination to proceed. However, consideration should be given to deferring or limiting this examination until the patient is sufficiently cooperative to allow radiographs of optimum diagnostic quality.

In this chapter we have taken a pragmatic approach of assuming that the dentist who is presented with a possible jaw fracture would refer that patient to a hospital Accident and Emergency Department rather than carry out a radiographic examination. Thus, our emphasis is placed upon dental trauma that you are most likely to manage in practice.

Choice of Radiographs

Trauma to the dentition

Traumatic injury confined to the dentition should be assessed with combinations of periapical or occlusal radiographs, as shown in Table 7-1, rather than by extraoral views such as panoramic radiography. In the immediate aftermath of trauma, complicated radiographic examinations may be difficult and painful; in such instances occlusal radiography offers the least traumatic examination and a more complete examination can be postponed until the next visit. Depending on the type of injury and its management, follow-up radiographs are required to assess the sequelae of damage or to review the success of treatment.

| Radiographs | Technique |

| Two periapicals | Paralleling technique. Use horizontal tube shift. |

| Two periapicals | Bisecting angle technique. Use horizontal tube shift. |

| Two periapicals | One paralleling and one bisecting angle technique. Uses vertical tube shift. |

| One periapical; one occlusal. | Paralleling technique for periapical film. Uses vertical tube shift. |

Dentoalveolar Fractures

The radiographs listed in Table 7-1 are also applicable to the assessment for dentoalveolar fractures. However, as the fracture may extend to involve several teeth or extend beyond the apical region, the value of larger occlusal films is greater.

Fractures of the Mandible

True (as opposed to dentoalveolar) jaw fractures are managed in hospital. As such it seems pointless for the dentist in general practice to carry out a radiographic examination when appropriate views, many of which are not pos-92 sible with simple dental x-ray equipment, will be selected by the hospital surgeon. Clinical examination is the best diagnostic test to determine whether referral is needed. A DPR is effective for diagnosis of all but high condylar mandibular fractures, but is best viewed by a radiologist or oral surgeon to confirm or exclude a fracture. If you take a DPR, then it is proper to include it with the referral letter to the receiving hospital department.

Trauma to the Teeth and Supporting Tissues

Trauma to the teeth is a common injury, especially during the first two decades of life. Surveys have shown that by 15 years of age over 25% of children demonstrate signs of traumatic injury to the teeth and that the peak incidence of injury occurs at about 9 years of age. At this age, root development of the incisor teeth is incomplete and the injury may result in cessation of root formation.

Luxation

Traumatic damage to the dentition and periodontal tissues is referred to as luxation injury. The different types of luxation and the important radiological signs are shown in Table 7-2.

| Type of injury | Clinical findings | Radiological appearance |

| Concussion | tender to touch, but no mobility | normal |

| Subluxation | mobile but not displaced | normal or slight widening or the periodontal ligament space |

| Lateral/medial luxation tooth | displaced laterally or medially | tooth may appear elongated or foreshortened with widening of the periodontal ligament space |

| Intrusion | tooth displaced apically into alveolus | tooth appears embedded into tooth socket |

| Extrusion | tooth partially displaced out of its socket | widening of the apical periodontal ligament space |

| Avulsion (total luxation) | missing tooth from socket | empty tooth socket |

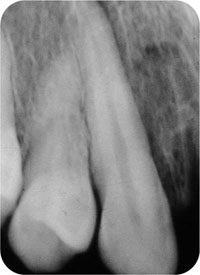

The radiographic appearance depends on the severity of the injury. A case of subluxation of the upper canine and lateral incisor is shown in Fig 7-1. The widened periodontal ligament space is visible as the only radiological sign. In lateral luxation the changes depend on the severity of the injury, but there is usually widening of the periodontal ligament space, because the tooth is displaced from its normal position (Fig 7-2). Palatally displaced, the teeth will appear more foreshortened (Fig 7-3), while teeth that have been intruded appear more apically positioned in their sockets (Fig 7-4). Extrusion may affect both the primary and permanent dentition. Fig 7-5 is a radiograph taken of a three-year-old who avulsed the lower left incisor and extruded both mandibular right incisors.

Fig 7-1 Periapical radiograph showing subluxation of the maxillary right canine and lateral incisor, as evidenced by the slight periodontal ligament widening.

Fig 7-2 Periapical radiograph showing a slightly luxated 13. It has been displaced buccally, appears elongated, and there is a widened periodontal ligament space mesially.

Fig 7-3 Occlusal view showing luxation of upper left incisor teeth. Because 21 is retroclined, the x-ray beam passes down its long axis, so it appears in plan view and very dense. Note also that the 22 has also been markedly displaced.

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses