7 Spreading infection

ASSUMED KNOWLEDGE

It is assumed that at this stage you will have knowledge/competencies in the following areas:

INTENDED LEARNING OUTCOMES

At the end of this chapter you should be able to:

CLINICAL FEATURES OF INFECTION

Local features

Many signs of infection (Fig. 7.1) are those of inflammation (pain, swelling, redness, heat), but not all inflammation is in response to infection: all these signs can be seen in rheumatoid arthritis. In infection you may also find suppuration (pus formation), an obvious cause and a greater systemic response.

Where swelling is largely due to oedema it is relatively soft. It tends to move within the tissues and accumulates at sites least constrained by fascia, as for instance, lips and eyelids (Fig. 7.2).

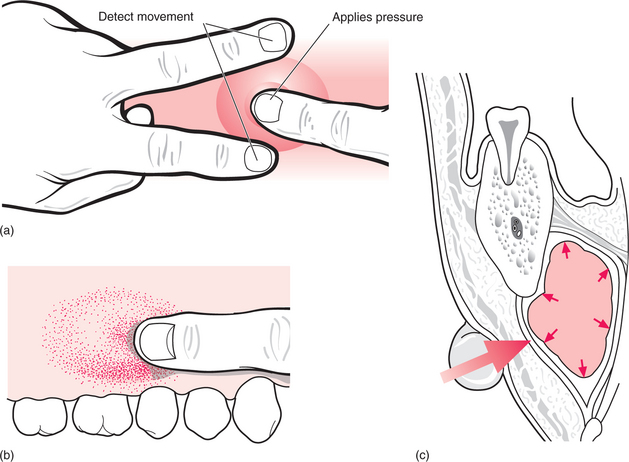

Many infections form pus; this adds to the swelling. A collection of pus is called an abscess. When close to the surface it may cause a yellowish discolouration of the overlying mucosa but, when deeper, all that will be seen is the redness of inflammation. Swelling due to pus has a very different feel to it from that due to inflammatory exudates. It is described as ‘fluctuant’, but that encompasses several different sensations detected by the examining fingers (Fig. 7.3). Classically, fluctuance is determined by placing two fingers at the sides of a swelling and detecting fluid movement caused by a third finger on the centre. That is not easy inside the mouth, where it may be possible to detect fluid movement only by running one finger along the swelling. For deeply placed abscesses in the neck, the feeling is more like tense springiness.

Fig. 7.3 Eliciting ‘fluctuance’.

When infection shows no significant localization of pus and has a greater tendency to spread it is called cellulitis. Where the predominant feature is pus formation it is called an abscess. However, almost all infections show elements of both and any infection starting as a cellulitis tends to localize over a period of days.

Spread of infection

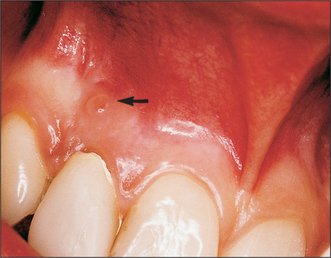

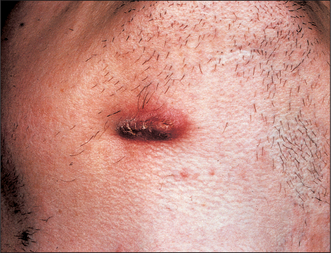

Most suppurative dental infections discharge into the mouth via a sinus, sometimes without obvious acute infection (Fig. 7.4), and usually onto the labiobuccal aspect of the alveolus. Apical infection from maxillary lateral incisors is more likely to drain palatally and from any tooth may point lingually, palatally or even onto the skin (Fig. 7.5). The commonest site of discharge onto skin is the point of the chin, arising from infection at the apex of a mandibular incisor. However, it is when, rarely, the infection tracks beyond the alveolus but does not readily escape onto a surface that the infections described in this chapter develop. The interlinked planes and spaces to which dental infections may spread have few absolute boundaries but can be summarized by considering the example of the third molar.

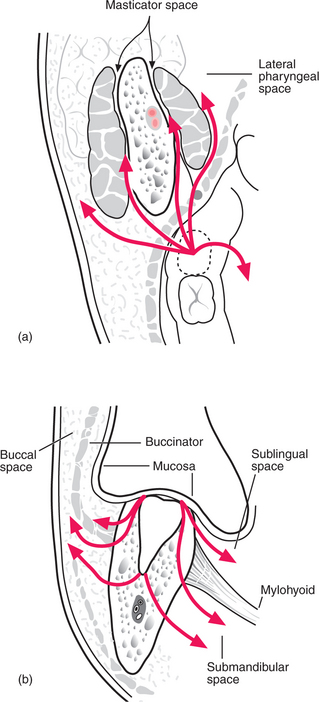

The crown of the part-erupted mandibular third molar, particularly if distoangular, may be below the attachment of buccinator/superior constrictor, allowing infection to escape laterally to the buccal space (Fig. 7.6), posteriorly to the masticator space or posteromedially to the lateral pharyngeal space. The masticator space is the potential space surrounding the ascending ramus and the elevator muscles of the mandible. Infection (whether or not pus has formed) makes these muscles resistant to lengthening, resulting in limited mouth opening, called trismus. Trismus in odontogenic infection indicates involvement of masticatory muscles.

Fig. 7.6 Routes of spread of infection from a lower third molar.

Apical infection from the lower wisdom tooth may escape laterally to the buccal space, producing swelling of the cheek above the lower border of the mandible. As the apex is below the attachment of mylohyoid, infection tracking medially enters the submandibular space, producing swelling in the neck, but sometimes upward bulging of the floor of the mouth too.

Systemic features

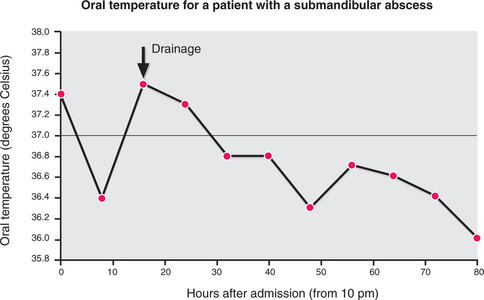

A substantial abscess may cause temperature ‘spikes’ (Fig. 7.7) on a daily basis. A single temperature reading taken at a trough between such spikes will be misleading. The pulse and respiratory rates rise with or slightly ahead of the temperature.

Fig. 7.7 A spiking temperature (oral measurement) in a patient with a submandibular abscess of dental origin.

DISTINGUISHING INFECTIVE FROM NEOPLASTIC DISORDERS

Generally, infection develops over a few days, but responds to removal of the cause and/or drainage of pus. Malignancies develop over weeks to months and do not respond to treatments suited to infections. Induration is common in long-standing infection, and may persist for days to weeks after treatment, but should show signs of improvement with treatment. By the time tumours are evidently infected, they are usually obviously ulcerated, which would be rare for an infection of dental origin.

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses