CHAPTER 7 Soft Tissue Management and Grafting

INCISIONS

FLAP DESIGN, ELEVATION, AND RETRACTION

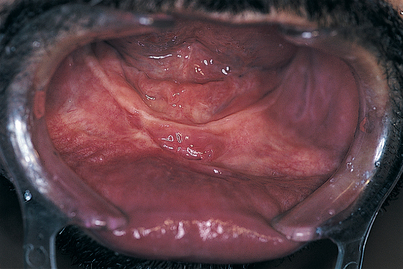

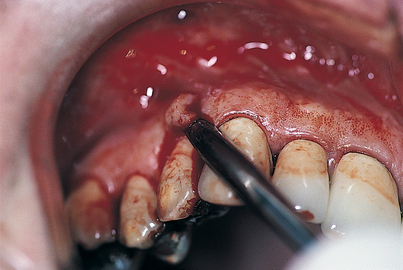

Careful, thorough, and complete flap design, and elevation without tearing or injuring the periosteum, is necessary for a smooth operative and postoperative course. For this purpose, the surgeon must have new or freshly sharpened periosteal elevators available (Fig. 7-3). The fibers must not be ripped or torn. Instead, they should be sharply incised at the level of the cortical bone; this requires a keen-edged elevator. Before each operation, the auxiliary staff should make sure that the elevators are as flawless and as sharp as new ones.

FIGURE 7-3. Periosteal elevators should incise, not tear, tissues. To perform their function, they must be kept sharp.

Flaps with releasing incisions should have bases that are wider than their alveolar margins, essentially trapezoidal (Fig. 7-4). If tooth areas are to be included in the surgical exposure, the gingival papillae should never be split, but rather should be included totally in the flap. Such gingival tissues must be elevated gently with a fine-pointed elevator only after thorough incision.

FIGURE 7-4. Flaps heal fastest when their bases are wide. Wide bases ensure the greatest amount of vascularity.

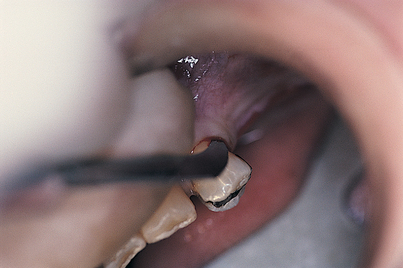

In areas where previous surgery or trauma has occurred or where evident scarring is present, or in other cases in which the investing tissues are resistant to easy, complete reflection, the procedure can be expedited using a technique that accomplishes this challenging task easily and consistently. The technique requires a small-toothed pickup forceps (Adson or Gerald) and a scalpel armed with a new BP No. 12 blade (Fig. 7-5). The practitioner lifts an edge of the flap with forceps so that the tip of the blade can gently stroke the scarred, adherent fibers in the fashion of a periosteal elevator. The practitioner proceeds a bit at a time, carefully elevating the flap until a zone is reached that allows conventional periosteal separation. This technique should not be attempted for the first time on a patient. Implantologists should practice on a cow mandible (which can be obtained from a butcher) until they achieve a high level of confidence in their ability to perform full-thickness reflection without perforating the mucoperiosteum (a serious but not always irrevocable occurrence). If the blade tip is kept against the bone and the strokes are made in a short, gentle fashion, the technique can be mastered readily. If the overlying mucosa is perforated, the laceration must be kept to a minimal length, the reflection is continued, and the subsequent surgery is completed. After suturing and closure, the iatrogenic laceration is closed with 6-0 Vicryl or Polysorb continuous horizontal mattress sutures using a fine, tapered, small half-circle (SH) needle (see the sutures and suturing section in Chapter 6).

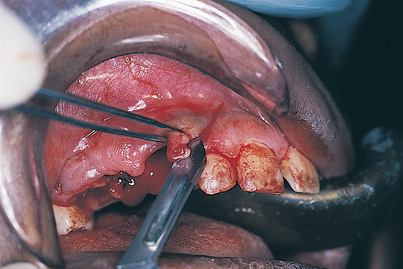

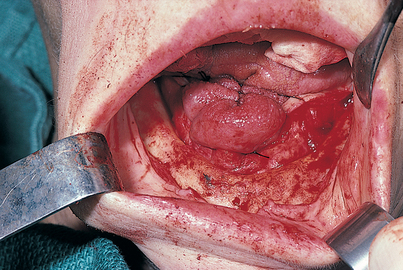

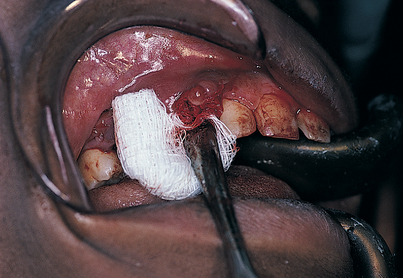

In two areas, the palatal and the mandibular facial, special care must be taken in the reflection of mucosal flaps so that the greater palatine and mental neurovascular bundles are protected. Such efforts are abetted if a 2 × 2 gauze sponge is inserted beneath the flap. By pushing the sponge with a periosteal elevator, the surgeon can enlarge the separation safely and accurately (Fig. 7-6). In this fashion, as a foramen is approached, it comes into view in a trauma-free fashion, sparing injury to its neurovascular bundle.

FIGURE 7-6. Flaps can be elevated in mucosal areas with minimal trauma by teasing them away from the bone; this is done by pushing a 2 × 2 sponge ahead of the periosteal elevator. The neurovascular bundle, when reached, is clearly visible, and the gentle progress of the sponge protects it from damage (see Figs. 7-8 and 7-9).

Once the flaps have been reflected, they must be managed gently. They should be kept well hydrated with saline-moistened sponges. The manner in which they are kept retracted also plays a role in subsequent healing. Retractors should be smooth surfaced; these include the Henahan, Seldin, beaver tail, and blunt-toothed rake (Mathieu) (Fig. 7-7). The staff should make sure that these instruments are not nicked or scratched. All rakes in the armamentarium should have blunt, not sharp, tips.

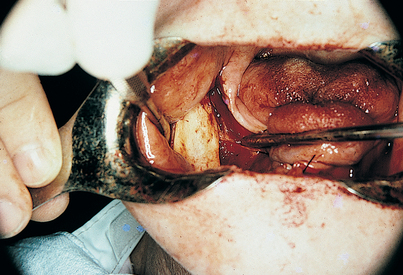

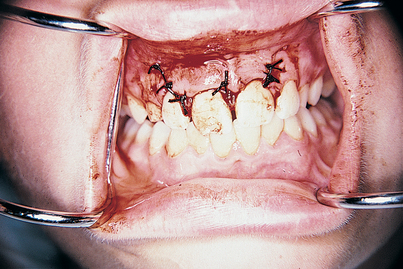

A suitable, convenient alternative to manual reflection is autoretraction using sutures. Buccal flaps may be sutured to the buccal mucosa. Palatal flaps may be sutured into a midline bundle, which keeps these tissues out of the operative field. Unilateral palatal flaps may be sutured to the teeth on the contralateral side, which keeps the surgical site well exposed without the need for retractors. Bilateral mandibular lingual flaps may be sutured to each other across the dorsum of the tongue; this configuration serves not only as an excellent means of retraction, but also as a competent tongue depressor (Fig. 7-8). Unilateral mandibular flaps may be kept retracted by suturing them across the dorsum of the tongue to teeth on the unoperated side.

In planning and designing flaps, the dental surgeon must not split papillae, frenula, or muscle attachments; rather, they should be included totally within the flap design. When palatal flaps are planned, all incisions should be made in the gingival crevices or at the ridge crest and never across the palatal mucoperiosteum. In this way, only full-thickness, total palatal mucosa is reflected (Fig. 7-9). If, as a worst case scenario, palatal tissues are segmented, the risk arises that the palatine artery will be cut; at best, such incisions retard healing and cause cons/>

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses