Chapter 7

Prosthetics and gerodontology

Contents

Relevant pages in other chapters Bridges—treatment planning and design, p. 260; occlusion, p. 238; acrylic and other denture materials, p. 640; casting alloys, p. 630; impression materials, p. 626.

Principal sources and further reading M. R. Y. Dyer 1989 Notes on Prosthetic Dentistry, Wright. J. C. Davenport 1988 A Colour Atlas of Removable Partial Dentures, Wolfe. J. F. McCord 2002 Missing Teeth: A Guide to Treatment Options, Churchill Livingstone. D. W. Bartlett 2004 Clinical Problem Solving in Prosthodontics, Churchill Livingstone.

Treatment planning

Reasons for prosthetic replacement of missing teeth

Disadvantages of prosthetic replacement

Treatment options for the partially dentate mouth

Treatment planning for partial dentures

NB It is important to enquire about previous denture history (just because a patient is not wearing a denture does not mean that they have not had one) and assess the reasons for failure or success. If a patient produces an extensive collection of unsuccessful dentures, unless there is an obvious and easily remedied fault, it is probably wiser to assume that you are unlikely to succeed where so many have failed and refer the patient for a specialist opinion.

Treatment planning for complete dentures

Discussing with the patient the limitations of dentures prior to their construction is more likely to be viewed as explanation, whereas leaving it until after fitting the dentures will be seen as making excuses!

Discussing with the patient the limitations of dentures prior to their construction is more likely to be viewed as explanation, whereas leaving it until after fitting the dentures will be seen as making excuses!

Principles of removable partial dentures

Definitions

Saddle

That part of a denture which rests on and covers the edentulous areas and carries the artificial teeth and gumwork.

Connector (major and minor)

Joins together component parts of a denture.

Support

Resistance to vertical forces directed towards mucosa.

Retainers

Components which resist displacement of denture.

Indirect retention

Resistance to rotation about clasp axis by acting on the opposite side to the displacing force.

Fulcrum axis

Axis around which a tooth- and mucosa-borne denture tends to rock when saddles are loaded.

Bracing

Resistance to lateral movement.

Guide planes

Two or more parallel surfaces on abutment teeth used to limit path of insertion, and improve retention and stability.

Survey line

Indicates the maximum bulbosity of a tooth in the plane of the path of withdrawal.

Free-end saddle

An edentulous area posterior to the natural teeth.

Stress-breaker

A device allowing movement between saddle and the retaining unit of partial denture.

Gum-stripper

A tissue-borne partial denture which can ‘sink’.

Dysjunct denture

Has complete separation between tooth- and mucosa-borne parts.

Swinglock denture1

Has a labial retaining bar or flange which is hinged at one side of the mouth and locks at the other.

Sectional denture

Made in two or more sections which are then fixed together with screws or other devices.

Classification

Kennedy

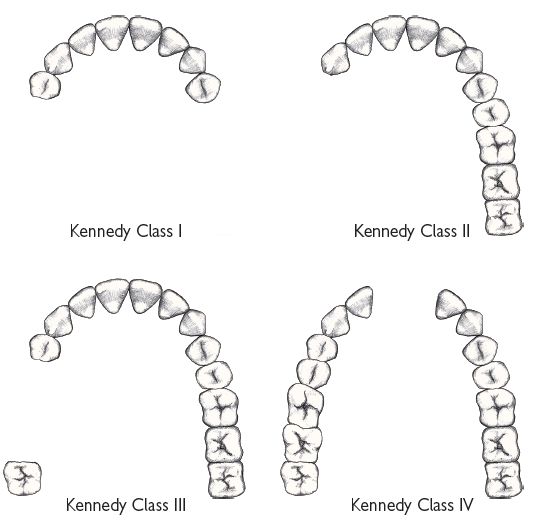

Describes the pattern of tooth loss (Figure 7.1):

| I | Bilateral free-end saddles. |

| II | Unilateral free-end saddle. |

| III | Unilateral bounded saddle. |

| IV | Anterior bounded saddle, only. |

Any additional saddles are referred to as modifications (except Class IV), e.g. Class I modification 1 has bilateral free-end saddles and an anterior saddle.

Fig. 7.1 Kennedy classification.

Craddock

Describes the denture type:

Acrylic versus metal dentures

Approximately 75% of the dentures provided in the UK have an acrylic connector and base. Although metal bases are generally preferred because the greater strength of metal permits a more hygienic design, an acrylic base is indicated for:

However, where financial constraints C/I a metal base, attention to the following may avoid the production of a gum-stripper:

Components of removable partial dentures

Saddles

can be made entirely of acrylic or have a sub-framework of metal overlaid by acrylic.

Rests

are an extension of the denture onto a tooth to provide support &/or prevent over-eruption. Occlusal rests are used on posterior teeth (usually over either the mesial or distal marginal ridge and fossa) and cingulum rests on anterior teeth. Rests may be wrought or cast; the latter is preferred for strength and fit.

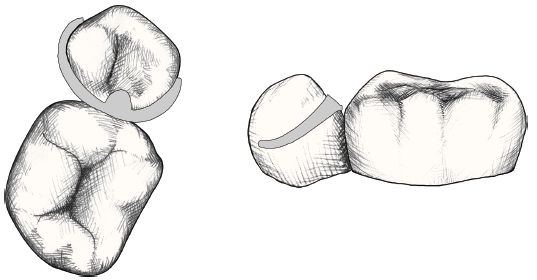

Clasps

provide direct retention by engaging the undercut portion of a tooth (Figures 7.2 and 7.3). The action of a clasp must be resisted either by a non-retentive clasp arm above the maximum bulbosity of the tooth or by a reciprocal connector. Clasps can be classified by their position (occlusally approaching or gingivally approaching) or by their construction and material.

Fig. 7.2 Occlusally approaching three-arm clasp.

One arm is the bracing reciprocal arm

One arm is the retentive component

One arm is the occlusal rest

Fig. 7.3 Gingivally approaching T clasp

Cast

(cobalt chrome) clasps are stiff, easily distorted and liable to #. However, provided they are limited to undercuts of 0.25mm, the advantage of being able to cast them as an integral part of a denture framework offsets these drawbacks.

Wrought

clasps are usually attached by insertion into the acrylic of a saddle. SS is the most commonly used alloy, but gold clasps are more flexible and easily adjusted (and distorted).

The stiffer the wire the smaller the undercut that can be engaged. This can be offset by reducing the diameter of the wire to ↑ flexibility (but ↑ the likelihood of #) or by increasing the length of the clasp arm (e.g. gingivally approaching clasp). Cast cobalt chrome can be too stiff for occlusally approaching clasps on premolar teeth. The actual design used depends upon:

Connectors

In addition to joining parts of the denture together, the connector can also contribute to support and retention.

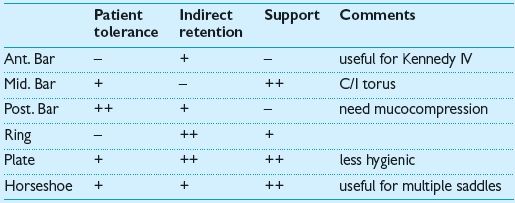

P/– connectors

–/P connectors

Figures 7.2 and 7.3 show the two most commonly used types of clasp.

Removable partial denture design

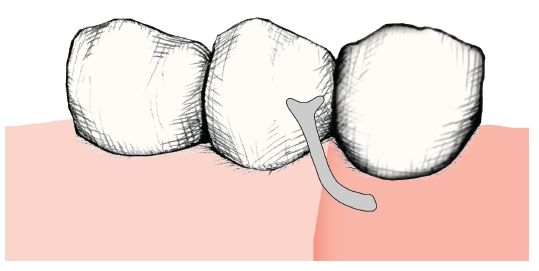

P/P design is carried out after assessment of the patient and with reference to any previous dentures (Figure 7.4). A set of accurately articulated study models is essential.

Fig. 7.4 Sectional partial denture.

Surveying

Objectives:

If the path of insertion is at 90° to the occlusal plane insertion of the denture will be straightforward; however, where the teeth are tilted or few undercuts exist, an angled path of insertion may be advantageous. Which provides more resistance to displacement during function is controversial.

A survey line can then be marked on the teeth to indicate their maximum bulbosity in the plane of the path of withdrawal. This is done using a dental surveyor.

Design

1. Outline saddles

Usually straightforward. If <½ tooth width or if in doubt of the need to replace a missing tooth, omit.

2. Plan support

Support can be tooth only, mucosa only, or both. Tooth-borne support (occlusal and cingulum rests) should be used wherever possible, as teeth are better able to withstand occlusal loading and support will not be compromised following resorption. Tooth and mucosa support are inevitable with large or free-end saddles and where plate designs are used. Tissue-only support should be utilized when no suitable teeth are available, and is less damaging in the upper than the lower arch, because of the palatal vault.

Need to assess the role of the denture, length of the saddles, the amount of support required (? denture opposed by natural or artificial teeth), and the potential of remaining teeth to provide support (root area in bone), before a final decision is made.

3. Obtain retention

Retention can be:

Direct

e.g. clasps, guide planes, soft tissue undercuts, or precision attachments. Of these, clasps are the most commonly used. The best arrangement is to use three clasps as far away from each other as possible. Guide planes help to establish a precise path of insertion and withdrawal. Need be only 2–3mm in length, reducing reliance on clasps.

Indirect

This is derived by placing components so as to resist ‘rocking’ of the denture around direct retainers, e.g. by the position of clasps and rests and the type of connector. Particularly important with free-end and large anterior saddles.

4. Assess bracing required

Bracing is provided by the connector, maximum saddle extension, and the reciprocal arms of clasps. Elimination of occlusal interferences ↓ need for bracing.

5. Choose connector

After consideration of above. Is there space in the occlusion to accommodate the chosen connector? Where possible the connector should be cut away from the gingival margins.

6. Reassess ?

as simple as possible ?aesthetic.

Instructions to technician

Should include written details and diagram. Where some confusion may arise over the precise position of a component it may be helpful to mark this directly on the cast. Computer aided design programs are now available.

Some design problems

The lower bilateral free-end saddle (Class I)

This presents a particular problem because of a lack of tooth support and retention distally, small saddle area compared to force applied, and distal leverage on abutment tooth in function (which ↑ with resorption). Possible solutions include:

Class IV

Can sometimes avoid unsightly clasps anteriorly by the use of:

Multiple bounded saddles

A horseshoe design, which utilizes guide planes for retention, may be indicated.

Clinical stages for removable partial dentures

1. Assessment and treatment plan,

p. 294.

2. Take first impressions

These are usually taken using alginate in a stock tray. For free-end saddles modify the tray first with compound or silicone putty.

3. Record occlusion

If ICP is obvious the occlusion can be recorded conventionally (p. 240) at the same visit as first impressions. If ICP is not obvious, wax record blocks will be required and a separate visit. Where there are no teeth in occlusal contact, the steps involved are the same as for recording the occlusion for F/F (p. 312). If there is an occlusal stop, but insufficient standing teeth to produce a stable relationship of the casts, the procedure is as follows:

4. Mounted casts are surveyed and denture designed,

p. 202.

5. Tooth preparation

may be required to:

6. Record second impressions

using a special tray. Alginate is the most commonly used material, but elastomers are preferable for deep undercuts. It is helpful to have a wax try-in before the framework is made. This enables you to confirm tooth position so that the retentive elements for the acrylic are placed appropriately.

7. Try-in of framework

8. Try-in of waxed denture

9. Finish

Once any fitting surface roughness is eliminated, the dentures are tried in separately, adjusting undercuts and contacts as required. The extension, occlusion, and articulation are then adjusted if necessary. Give the patient written and verbal instructions, and a further appointment.

Rebasing P/P

Acrylic mucosa-borne dentures can be rebased at the chair-side with self-cure materials, but difficulty may be experienced in removing the denture in the presence of undercuts, and the materials are generally inferior to the original denture base. Alternatively, P/P can be rebased in the laboratory by means of a technique similar to that used for F/F (p. 318). Alternatively, make a new denture. For cast metal dentures an impression can be recorded of saddle area using an elastomer or ZOE, whilst holding denture by the framework. In all cases care must be taken to avoid the introduction of occlusal errors, e.g. ↑ OVD.

Immediate complete dentures

When the remaining teeth have a poor prognosis management depends upon whether the patient is already a partial denture wearer or not.

Rx alternatives for patients with no previous denture experience

Rx alternatives for partial denture wearer

Types of immediate complete denture

Flanged dentures are preferable as they afford better retention and make subsequent rebasing easier. However, where a deep labial undercut exists into which it would be impossible to extend a flange, the choice is either surgical reduction or an open-face denture. Most patients choose the latter.

Clinical procedures

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses