Direct Restorations in the Anterior

Indications for and Limitations of Direct Restorations

The main indications for direct restorations are as follows:

The main advantages are as follows:

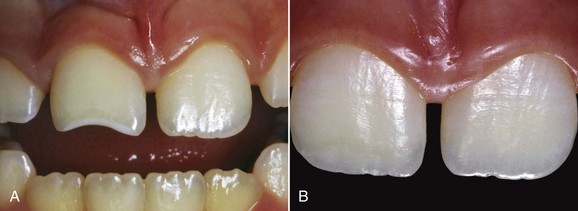

The criteria for choosing adhesive restoration are as follows (Figures 7-2 to 7-6):

• Extent of the lesion and the number of teeth involved

• Tooth function and status of the antagonist tooth

• The patient’s age and needs, which are particularly important in the field of cosmetic dentistry; patients should be advised and helped, and their demands should not be ignored

• Anatomic and functional recovery of the tooth; the possibility of restoring the correct form and function after proper professional training

Shade and Morphologic Mapping

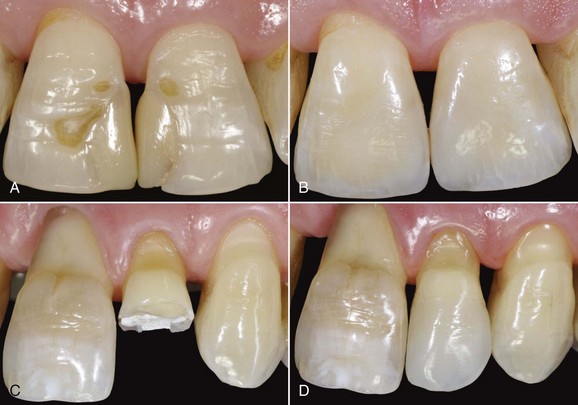

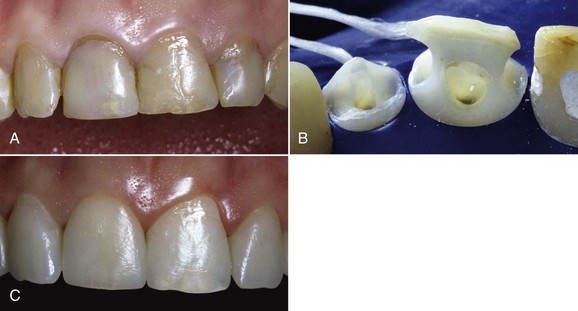

In the case of Black Class IV restorations, the most logical way to control the thickness of the material is to prepare a diagnostic wax-up of the missing portion on a plaster cast mounted in the articulator, and then in the dental laboratory fabricate a silicone tray (Shore hardness about 95) that will be used as a template for the palatal side (Figure 7-7). Thickness control on the buccal aspect is achieved through precise shaping without a great deal of excess material.

Preconditions

There are several preconditions for layering a restoration.

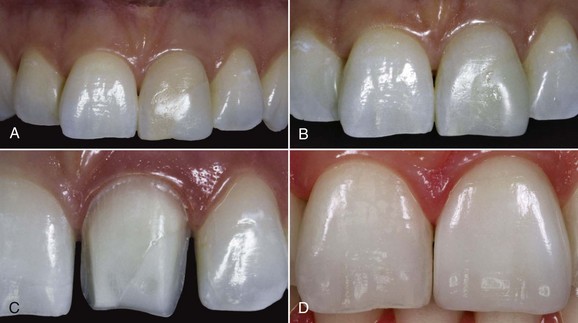

• The general shape of the tooth—both macroscopic and microscopic—and especially that of enamel and dentin plays a leading strategic role in the final result. Color is an added value.

• The shade of the dentin represents a low-definition aspect and does not play a major role; opacity and shape are much more important.

• Reproduction of the enamel is considered a high-definition aspect because color, opacity, and shape are equally important; its realization requires the operator’s close attention in order to grasp every detail to be reproduced.

Shade Parameters

Psychological Parameters

In 1969 Henry Munsell introduced parameters based on visual and cognitive perception that, translated into dental terms, mean hue, chroma, and value; the last of these is the most significant for dental purposes (Figures 7-8 to 7-10).

Figure 7-8 Value: the amount of gray in a shade.

Value corresponds to brightness—that is, the amount of light that is reflected, refracted, or absorbed by a surface—and it is influenced by the type of surface finish. As shown in Figure 7-8, the interaction between light and a glass object produces dark and clear areas with a low value, alternating with clearer and more reflective high-value zones, depending on the surface finish: smooth, orange peel, or sanded. In short, analysis of a tooth value can be compared with a black-and-white photograph and can be divided into two parts:

Choice of Shade

Anatomic Preconditions

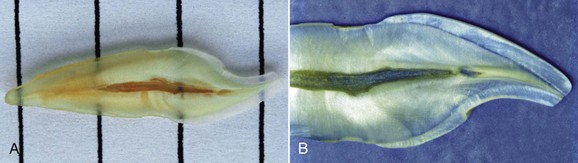

In Figure 7-11 we can see that the inner layers of dentin (close to the pulp) have a high value, whereas in the outer layers (toward the enamel) chroma increases and the value is lower. The inner enamel layer (toward the dentin) has a low value, whereas the outer one has a high one.

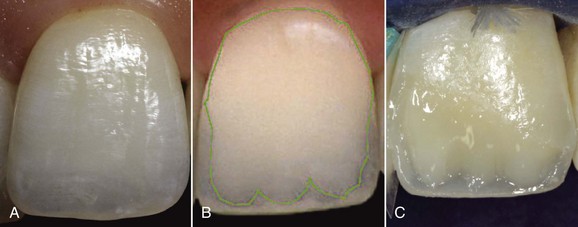

The most important parameters in shade reproduction with composite materials are opacity, shape, and shade for the dentin, and opacity, thickness, and surface texture for the enamel (Figures 7-12 to 7-14).

Shade Reproduction

Figure 7-11 Assessment of chroma and value in natural teeth.

Figure 7-12 Analysis and reproduction of dentin.

Philosophy of Composite Materials

Most marketed composites have a number of limitations.

• They are difficult to compare based on the names conventionally written on the labels.

• There is no agreement among composite manufacturers concerning the level of opacity, shade depth, and amount of masses required for a line of composite materials—that is, there are very simple lines with a single opaque composite, and others that offer three or more.

• Masses are usually too transparent, which means that they have a low value and look gray. This makes the choice of shade even less important; the value is further lowered after curing, especially for the more transparent masses.

• The shades of many materials do not match the Vita shade guide, and on average they have lower chroma and value.

Figure 7-15 shows machine-made enamel samples with the same thickness and polishing, although they differ in opacity. We can observe more transparent samples with a low value and others that are more opaque with a high value.

Figure 7-15 Value: brightness and opacity.

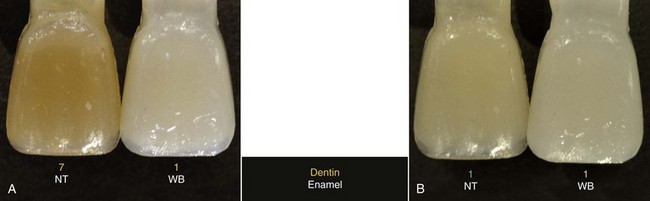

The samples shown in Figure 7-16 were obtained by overlapping cores of dentin (approximately 2.5 mm) on thick enamel shells (approximately 1.5 mm). In Figure 7-16 the left sample is obtained with chroma dentin 7 (very deep shade) and NT enamel (Neutral Transparent with a low value); the sample on the right side is made with chroma dentin 1 (diluted color) and WB enamel (White Opaque with a high value). The shades of the sample teeth obtained with these layerings are logical and consequential, whereas the color of the sample on the left side of Figure 7-16—obtained with chroma dentin 1 and NT enamel—cannot be grasped immediately. Using a low-chroma dentin one would expect a light-colored tooth, but its association with a thick layer of NT enamel lowers the value drastically, overpowering the dentin in the final result. This demonstrates that overlaying completely different enamel composite shades on the same dentin affects value.

Figures 7-17 and 7-18 exemplify the behavior of several composite materials layered over a thick core to reproduce dentin, over which thin vertical columns differing in opacity, chroma, and hue were applied. Given the />

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses