Chapter 7

Conscious Sedation1: What It is and

When to Use It

Aim

The aim of this chapter is to:

-

define conscious sedation

-

position paediatric dental sedation in the United Kingdom in relation to other parts of the world and to medicine

-

present the relevant child anatomy and physiology in relation to paediatric dental sedation

-

outline the risks, benefits and complications of paediatric conscious sedation

-

explore when to use conscious sedation.

Outcome

The information in this chapter should enable dental practitioners to determine when sedation is appropriate for the management of an anxious child.

Introduction

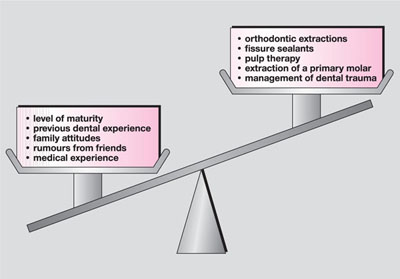

In previous chapters various options for successfully managing children in dental practice have been presented. But for some children conscious sedation may be needed to augment an existing behavioural management strategy. The dental team should not forget, however, that behavioural management strategies continue to underpin the delivery of dental treatment under conscious sedation. So in paediatric dentistry, sedation must always be combined with behavioural management – integrated and tailored to meet not only the needs of each child, but also each planned procedure (Fig 7-1).

Fig 7-1 Anxiety baggage.

Conscious sedation for children is different from conscious sedation for adults. A child’s anatomy and physiology differ from an adult’s, which means that the way they react to sedative drugs is also different. Adult studies cannot be applied to children just as paediatric studies cannot be extrapolated for use in adults. Moreover, whilst there is a huge research evidence base supporting paediatric dental sedation, this has mainly been reported by specialist paediatric dentists outside the United Kingdom.

What Sedation is Not

Remember that conscious sedation adds to conventional behavioural management techniques it does not replace them, as sedative drugs alone cannot replace good communication or create the right environment in which the child feels safe. Moreover, like all other treatment provided for children, conscious sedation must not be separated from an acknowledgement of each individual child’s level of emotional and intellectual maturity. In short, conscious sedation for children is not a “quick fix”. Instead, it is a part of the armamentarium that dentists use to help children accept dental treatment.

So What is Conscious Sedation for Dentistry?

Different definitions of dental sedation may be found in the literature, for example:

“A state of depression of the central nervous system enabling treatment to be carried out, but during which verbal contact with the patient is maintained throughout the period of sedation.”

“The administration of an agent prior to dental treatment for the purpose of obtaining an alteration of the patient’s psychic response and subsequent relief of apprehension and anxiety.”

“A minimally depressed level of consciousness that retains the patient’s ability to maintain a patent airway independently and continuously, and respond appropriately to physical stimulation and/or verbal command… the drugs and techniques used should carry a margin of safety wide enough to render unintended loss of consciousness unlikely.”

While the definitions vary, the underlying theme is clear: sedation is the use of agents to decrease anxiety levels while maintaining a responsive patient. Within the United Kingdom the contemporary guidance must be followed and all suggested practice within this text complies with the current General Dental Council (GDC) recommendations for conscious sedation. The current GDC definition of conscious sedation is as follows:

“A technique in which the use of a drug or drugs produces a state of depression of the central nervous system enabling treatment to be carried out, but during which verbal contact with the patient is maintained throughout the period of sedation. The drugs and techniques used to provide conscious sedation for dental treatment should carry a margin of safety wide enough to render unintended loss of consciousness unlikely. The level of sedation must be such that the patient remains conscious, retains protective reflexes, and is able to understand and to respond to verbal commands.”

A World-Wide View of Paediatric Dental Sedation Literature

There has been extensive research into sedative drugs and drug combinations throughout the world with oral, intravenous, rectal and inhalational routes being reported. Given this variation, it is often difficult to discover whether or not the sedative level achieved matches the contemporary definition of conscious sedation. Indeed, in many cases it is clear that the reported regimen is unlikely to comply.

A prime example of this is “deep sedation”, which has been defined as

“a controlled state of depressed consciousness or unconsciousness from which the patient is not easily aroused, which may be accompanied by a partial or complete loss of protective reflexes, including the ability to maintain a patent airway independently and respond purposefully to physical stimulation or verbal command.”

Thus the deep sedation practised, for example, in North America, chiefly by paediatric dentistry specialists, is considered in the United Kingdom to be general anaesthesia and, as such, the operating dentist is required not only to have a qualified anaesthetist present to administer the sedation but also be sited on or near an acute hospital.

United Kingdom Culture and Practice

Cultural differences exist between nations, and these set limits on the way dentists manage anxious or uncooperative children. In the United Kingdom, dentistry and general anaesthesia have close historical links that may partly explain why general anaesthesia is used far more for dental extractions in children compared with most other countries. On the other hand, the papoose board, a restraining device most commonly used in North America to facilitate dental treatment, is less acceptable to British parents for the same purpose. Similar reservations exist about some forms of sedation for dental treatment, especially in a primary care environment. For example, rectal sedation, which is successfully used in several countries and has a good evidence base to support its use, is unpopular with United Kingdom parents and therefore not usually employed.

Therefore, one of the difficulties in interpreting literature from different sources is determining its applicability to United Kingdom practice. This includes how acceptable the technique will be to the United Kingdom population and whether or not it complies with GDC guidelines. In other words, the fact that a study demonstrates that a particular regimen is successfully used in children abroad does not mean that that the same protocol can be used in the United Kingdom. Things that are unlikely to be acceptable to most United Kingdom practitioners and parents include:

-

combinations of drugs

-

child restraints (papoose board)

-

mouth props.

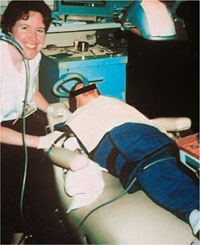

Moreover, where combinations of techniques are employed it is hard to determine how much of the success is due to the sedative regime and how much to the management techniques used. Not surprisingly, some of these deep sedation and restraining techniques also raise questions concerning informed parental consent, professional acceptance and the possibility of litigation (Fig 7-2).

Fig 7-2 Sedation in other parts of the world may not meet UK standard of conscious sedation (MTH in the USA).

Sedation in Medicine

It is unwise to attempt to crowbar sed/>

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses