THE DIODE LASER IN FIXED PROSTHETIC RESTORATIONS: AIMS AND POTENTIAL

Enrico Gherlone – Francesca Cattoni

6.1 THE AESTHETICS AND CONDITIONING OF SOFT TISSUES

I. Concepts of aesthetics in fixed prosthetic rehabilitation and aesthetic objectives

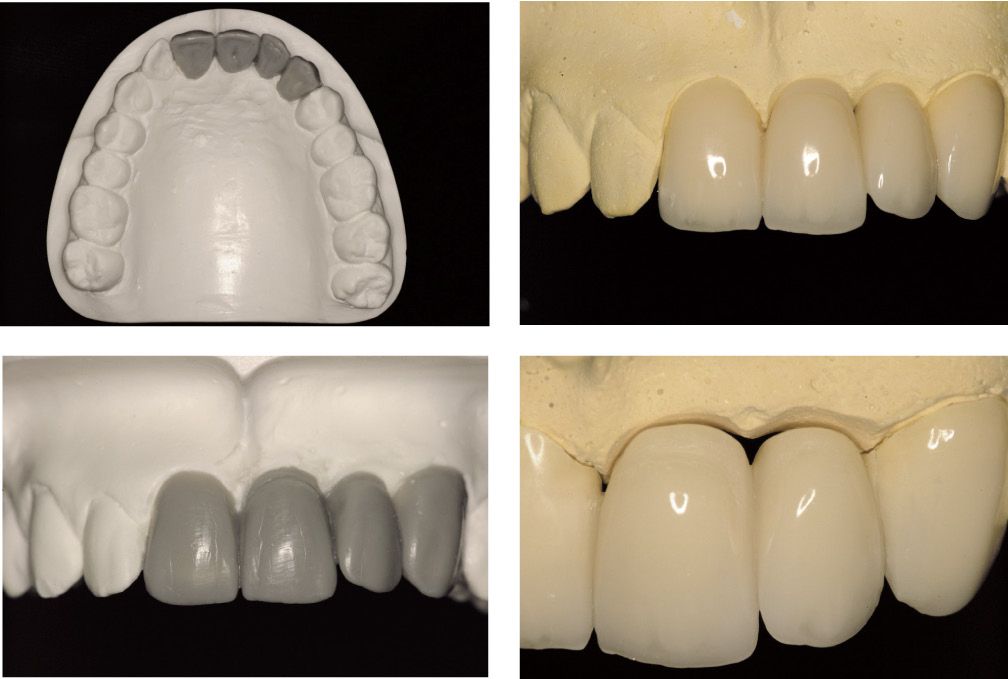

Aesthetics, understood in its broadest sense, is a discipline that, over time, has undergone a unique process of reappraisal and affirmation. The mass media, in particular, offer us numerous models of beauty, and most of these examples are, indeed, widely imitated. These models present physical beauty as the key to success, both personal and interpersonal, and this explains the strong and widespread growth of the interest in, and demand for, all kinds of treatment, both cosmetic and genuinely aesthetic, and also in the expectations, in terms of personal results, that are associated with them [1]. Modern dentistry, too, is affected by this increase in the importance that is attached to results that are not only functional but also, indeed above all, aesthetically valid, and as result is subjected to extremely pressing demands (Figure 6.1a-d). It is clear that the face, the smile and the teeth, and therefore also the tissues supporting and surrounding the teeth, are among the factors that contribute the most to the aesthetic appearance of a human being [2] (Figure 6.2a-b). The manufacture of products that restore or respect the fundamental parameters of oral aesthetics, namely the shape and colour of the teeth, the smile line and so on, demands considerable knowledge and experience on the part of the operator, close collaboration between the members of the dental health team (including of course the dental technician responsible for making the product in question), and an in-depth understanding of the available techniques, materials and technologies, both established and innovative, including new technologies like the laser (Figures 6.3-6.4).

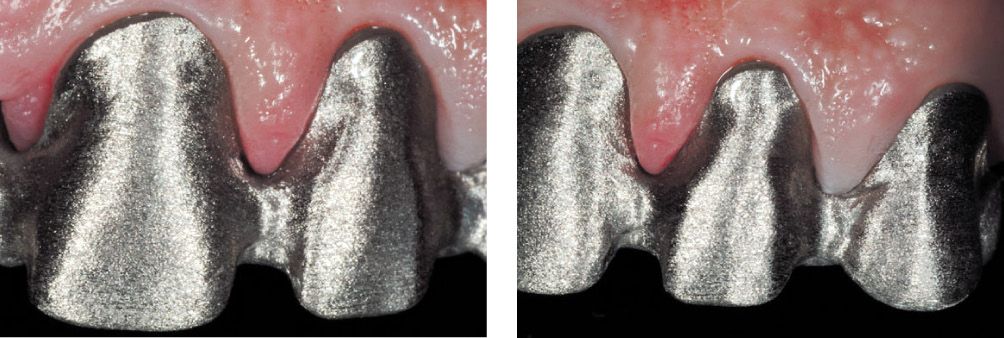

Figure 6.1a-b-c-d • Examples of aesthetic smiles.

Figure 6.2a-b • Examples of aesthetic teeth.

Figure 6.3 • Healthy gum tissue.

Figure 6.4 • Aesthetic impact of healthy gum tissue.

II. Aesthetic objectives: Traditional methods

The importance of preparation and of the temporary prosthetic restoration

The aim of prosthetic-reconstructive therapy, prosthetic-conservative therapy, and partial or total prosthetic implant therapy, is the rehabilitation (morphological, functional and aesthetic) of the patient’s teeth and tissues.

In this context, we strive to restore the single patient to the best possible conditions and to meet his or her expectations (Figures 6.5-6.6-6.7). Assuming that every patient submitted to reconstructive therapy has been carefully selected from both a periodontal (Figure 6.8) and a gnathological (Figures 6.9-6.10-6.11) point of view to rule out the need for subsequent treatments, the stages that the dental prosthetist must carefully exploit in order to achieve the first improvements of the patient’s functional and aesthetic conditions are:

- preparation of the teeth

- tissue conditioning through application of a temporary prosthetic restoration.

Figures 6.5-6.6-6.7 • Initial and temporary restoration stages during a complex prosthetic rehabilitation.

Figure 6.8 • The importance of good periodontal health in prosthetic restoration.

Figures 6.9-6.10-6.11 • Laboratory stages in a complex prosthetic rehabilitation.

The preparation of the teeth and the importance of the temporary restoration:

The preparation of the teeth is the first step in the prosthetic rehabilitation process.

Its aim, respecting the patient’s anatomical and aesthetic characteristics, is to replace or cover one or more teeth, avoiding damaging them and modifying them only in order to improve the condition of the tissues of the stomatognathic system [3] (Figure 6.12).

Figure 6.12 • Tooth preparation.

The preparation phase is conditioned by a number of factors:

- biological, that is, periodontal: it is, in fact, essential to intervene on tissues initially defined healthy, in order to be able to guarantee a “predictable” long-term outcome of the treatment. This is because presence of acute or chronic inflammatory processes would certainly jeopardise the reconstruction phase;

- physical-mechanical: it is necessary, using burs carefully selected for the clinical conditions of the specific case, always to create preparations designed to optimise the retention of the prosthesis, that is, to ensure its stability and strength in the oral cavity.

Nevertheless, problems can arise that the dental prosthetist must overcome.

Often the preparation of the pillar teeth is complicated by unfavourable situations, such as: the need to position the prosthetic margin under the gingival margin (for example, when the vertical dimension is limited or the stump is too short), a problem that can lead to loss of retention; the presence of irregular and asymmetrical vestibular gingival contours in areas of high aesthetic impact (the upper frontal area), the presence of large or misshapen interdental papillae, or gingival hypertrophy due to inflammatory-pharmacological causes or mechanical traumas [4,5].

In these cases, it is necessary to intervene not only on the teeth, but also on the soft tissues.

The methods the dentist can use to this end range from remodelling through the removal of only minimal quantities of tissue to major surgical interventions on the gingival tissues and mucosa in the most severe cases.

Small modifications can also be achieved during the preparation phase through the application of a carefully fashioned temporary prosthetic restoration, designed to improve functional and aesthetic defects.

The temporary restoration is the “test bed” of the definitive intervention, and in cases in which it serves not only to protect but also to reshape dental soft tissue, it may be seen as the first (trauma-free) step towards achieving the desired aesthetic outcome [6] (Figure 6.13a-d).

The result can often be improved by modifying the temporary restoration itself, either by adding material (e.g. resin or composite) or by taking material away (e.g. reducing the incisal margins to evaluate the shape of the teeth, the phonetics and the aesthetics), depending on the single case, always being careful, of course, to give the tissues time to heal and to adapt correctly to the morphology we have created.

We should always have at our disposal the means and technologies needed to carry out minor, moderate or major interventions on the oral soft tissues. In this way, we are always equipped to carry out the therapy that may be required, in the single case, to achieve the desired clinical result.

Whenever we are talking about the remodelling of gingival tissue, it is important to distinguish between:

- interventions that need not affect the bone tissue

- interventions that necessitate the removal of some bone tissue.

The second category is the direct province of the periodontologist.

It covers all situations in which active intervention on both soft tissue and bone is necessary not only to correct the morphology of the gingival tissue and oral mucosa, but also to restore correct anatomical soft tissue-bone relations, as in the case of clinical crown lengthening. In these cases the approach is prevalently surgical. The former, instead, includes so-called moderate interventions, in which surgery is required but only of the soft tissues, without any involvement of the alveolar bone (Figure 6.14).

Interventions in this category can be carried out using different instruments:

- electric scalpels

- scalpels

- burs

- lasers

Figure 6.13a-b-c-d • Planning and construction of the temporary restoration.

Figure 6.14 • A minor, laser-assisted gingivoplasty procedure.

III. The importance of the DIODE laser

The use of the laser beam as a cutting instrument in various branches of surgery, including oral surgery, has been the focus of many studies over the past decade [10,15,16,19,20].

The laser, by definition, produces very precise incisions and at the same time exerts a variable haemostatic action (obviously depending on the type of laser used and the type of target tissue) [7].

The laser most widely used in prosthetic dentistry is the DIODE LASER.

This term covers a range of machines with wavelengths ranging from 808 to 980 nm that display high efficacy when used on oral soft tissues, given that diode laser irradiation is efficiently absorbed by pigments such as melanin and haemoglobin, and also to an extent by water; furthermore, the fact that diode lasers use optical fibres (with 300-400 micron diameters) to transmit energy makes them manageable and suitable for use in the clinic [8].

In this field, the diode laser is used at low power (1.5-3W) in order to avoid unnecessarily damaging or overheating the target tissue.

Incisions made by a diode laser are wounds that must heal by second intention, without the use of sutures and often without the support of antibiotic therapies, given the capacity of the laser beam to exert a decontaminating action [9].

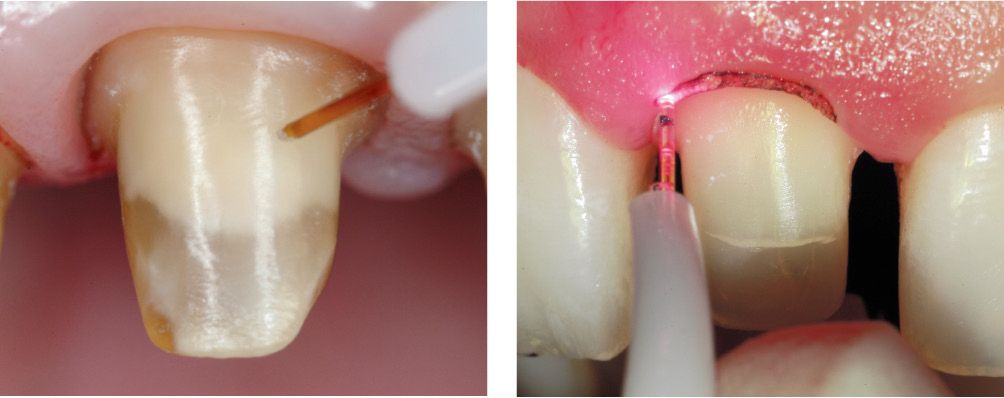

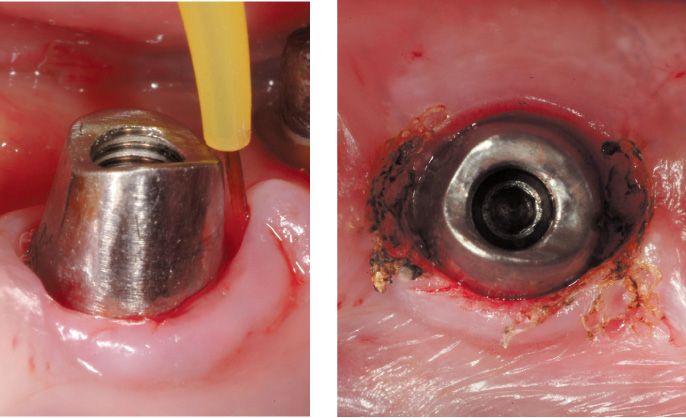

In surgical applications, the diode laser is used with an optical fibre that is brought into direct contact with the target tissue, almost mimicking the action of the traditional scalpel (Figures 6.15-6.16).

Figures 6.15-6.16 • Examples of the use of optical fibres on dental tissue.

An important advantage of laser treatments, assuming they are correctly performed, is their “ATRAUMATICITY” at the level of the oral soft tissues.

This is attributable to the extreme precision with which the beam is delivered to the target tissues (leaving the adjacent tissues intact) [10]. This advantage is further enhanced by the fact that laser treatments are also less painful.

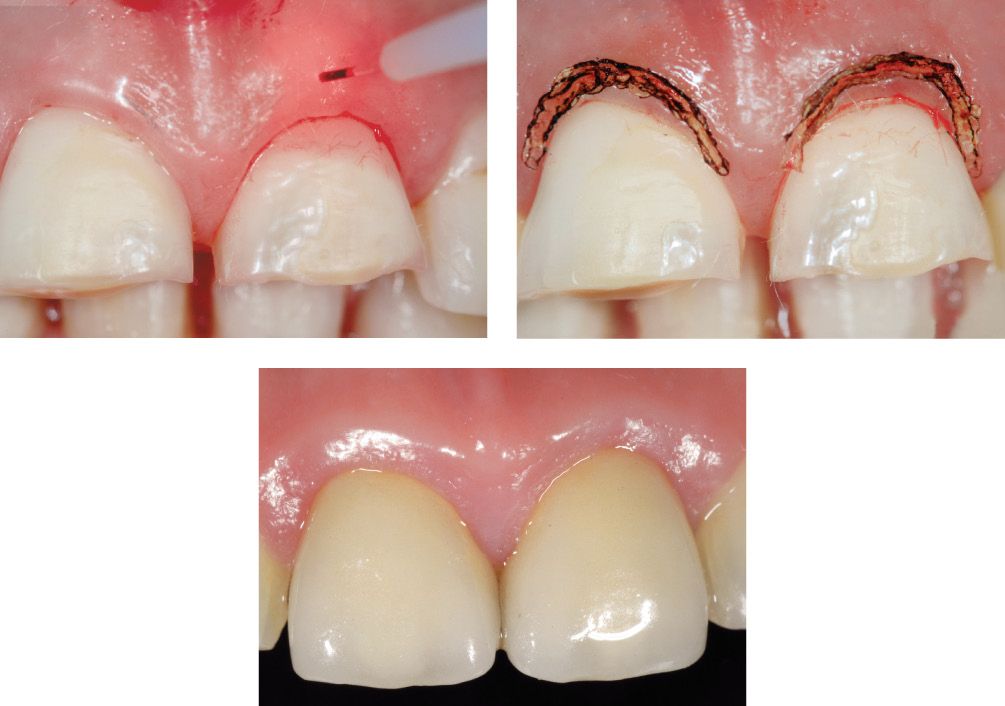

As regards healing after laser treatment (Figures 6.17-6.18-6.19), many studies have clearly shown that laser wounds to the oral mucosa heal more slowly in the immediate post-operative period, but that healing is more effective in the medium and long term.

Figures 6.17-6.18-6.19 • Stages in laser treatment of oral soft tissues and subsequent tissue healing.

What this observation reflects is a delayed onset of the inflammatory and repair processes and, as a result, of the processes of epithelial regeneration and collagen fibre production.

This actually has a beneficial effect: the edges of the wound are less subject to tension in the first stage of healing, and this ultimately results in a better aesthetic outcome.

In short, the delayed epithelialisation of the laser wound is due to a reduced inflammatory and thus reparative response in the first stage of healing, but the aesthetic outcome is actually improved as a result of this as there is less contraction of the wound edges.

In this regard, the laser differs from other thermal energy-based technologies, such as the electric scalpel [11-14].

In the light of these considerations, it is reasonable to argue that there exist many clinical situations involving the oral soft tissues that could benefit from the use of the laser beam as a surgical instrument.

These applications range from:

1. simple reshaping of the gums for aesthetic or prosthetic purposes (this category includes operations such as gum contouring, gingivectomy, gingivoplasty, frenectomy and others);

to

2. removal of oral tissue in oral pathology.

IV. LASER-assisted TISSUE REMODELLING

The diode laser can be used in all clinical situations in which the oral soft tissues, in order to be restored to favourable functional and aesthetic conditions, need to undergo a greater or lesser degree of “remodelling” [10,15,16].

Operators frequently encounter clinical situations in which surgery is essential because of the presence of excess tissue, or tissue that has an abnormal shape or size, or is simply anti-aesthetic; in many cases the intervention has to be carried out immediately, and it will often coincide with the preparation and application of the temporary prosthetic restoration [17].

This consideration underlines just how crucial it is, in order to obtain an optimal result, to use a machine that respects the gingival tissue and guarantees not only high-precision incisions but also a decontaminated and “bloodless” operating field (even in patients with coagulation disorders who often have to take specific drugs) [18]; the latter condition ensures optimal visibility for carrying out different types of tissue correction (Figures 6.20-6.21-6.22).

Figures 6.20-6.21-6.22 • Laser-assisted gingivectomy: treatment stages and healing (after 7 days).

The precision of diode lasers is to be attributed largely to their use of optical fibres as a means of transmitting the light emitted; the optical fibres are also responsible for the user-friendliness of the laser as well as for the various other advantages mentioned [8]. Any laser-assisted approach in oral soft tissue surgery and periodontology must always be preceded by a careful evaluation of the biological width of the teeth to be treated.

This is necessary in order to rule out the need for osteotomy following the ablation of some of the gingival tissue surrounding the teeth, because “laser-assisted gingival remodelling” implies intervention, that is incision, ONLY at the level of the gingival or oral mucosal tissue; the underlying bone structure is not altered in any way [16].

Laser-assisted tissue remodelling does, however, necessitate the use of a local anaesthetic.

One of the main attributes of the laser, which makes it particularly suitable for interventions on the oral soft tissue (because it respects this tissue), is the “atraumaticity” [10] that is guaranteed by its capacity to target only the area to be treated, leaving the adjacent tissue intact; for this reason, the laser is recommended whenever it is indispensable to preserve, as far as possible, the tissue that is present, irrespective of the clinical need to reshape it.

In other words, it is recommended:

- in the anterior segments of the oral cavity (these are areas of high aesthetic value, in which laser-assisted remodelling must be preferred in order to avoid highly anti-aesthetic scarring and to preserve the existing tissue);

- in bleeding-prone areas or patients (both healthy patients but particularly patients with coagulation disorders);

- in areas where there is little gingival tissue;

- in peri-implant areas.

Protocol for using the diode laser

Laser treatments of soft tissues are carried out following infiltration of a local anaesthetic, sometimes with the addition of a vasoconstrictor in a concentration of 1:100,000/1:200,000.

An optical fibre with a 300/400 micron diameter is selected.

The optical fibre must be used in direct contact with the tissue to be remodelled or removed, and the operator should be careful to execute sufficiently rapid yet extremely precise movements that will allow him to make the necessary tissue incision while reducing to a minimum the contact between laser and tissue (i.e. the duration of the exposure and thus the risk of overheating).

The optical fibre must be absolutely stable during the cutting strokes and must also be cleaned scrupulously after almost every stroke in order to eliminate the tissue fragments that tend to adhere to it.

The optical fibre is easily cleaned either with the laser turned off, using damp gauze, or with the laser running, by inserting it to a depth of 1-3 mm into a cotton roll and then removing it immediately.

Before being used on oral tissues the optical fibre must always be activated as follows: the laser machine is turned on and the fibre is trained on a dark background (articulation paper).

The optical fibre must always be held perpendicularly to the tissue to be cut, unless the intention is to make a bevel cut in the tissue itself as a means of conserving more of the keratinised vestibular gingiva; in this case the optical fibre is held at an angle of 45 degrees in a vestibular-palatal or vestibular-lingual direction.

The parameters of use for a diode laser (810-980 nm) are the following:

- Power: 1.5-2.5 Watts

- Emission: continuous wave

- Time: variable, depending on the specific clinical case.

Remodelling does not need to be followed by antibiotic treatment to favour healing.

The patient is simply advised to use a 0.25% chlorhexidine mouthwash, undiluted, for 7 days to keep the treated site clean and disinfected.

Clinical case (Fig.6.23a-s)

Clinical case: example of gingival contour remodelling.

Figure 6.23a,b • Clinical case before treatment.

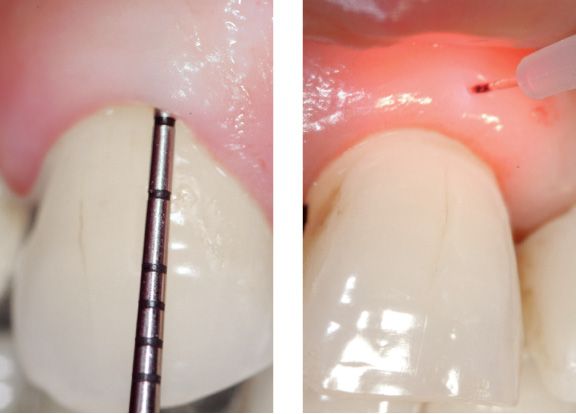

Figure 6.23c • Assessment of periodontal health and measurement of biological width.

Figure 6.23d,e • Laser-assisted gingivoplasty.

Figure 6.23f-g • Laser-assisted gingivoplasty.

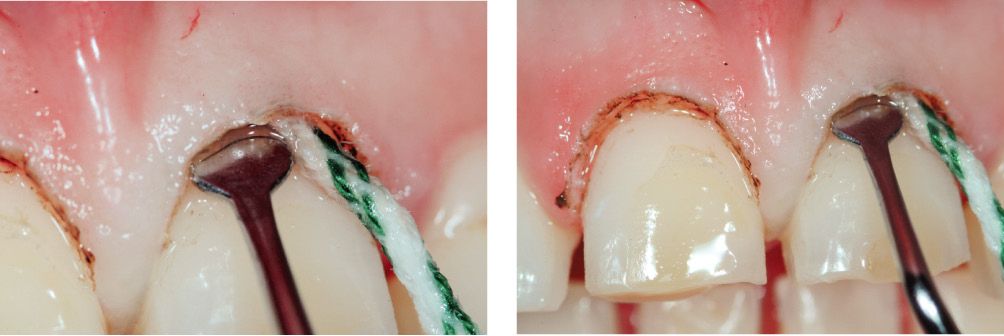

Figure 6.23h-i • Placement of retraction cord.

Figure 6.23l-m • Tooth preparation.

Figure 6.23n • Opening of the sulcus using a diode laser.

Figure 6.23o-q • Healing of gingival tissues.

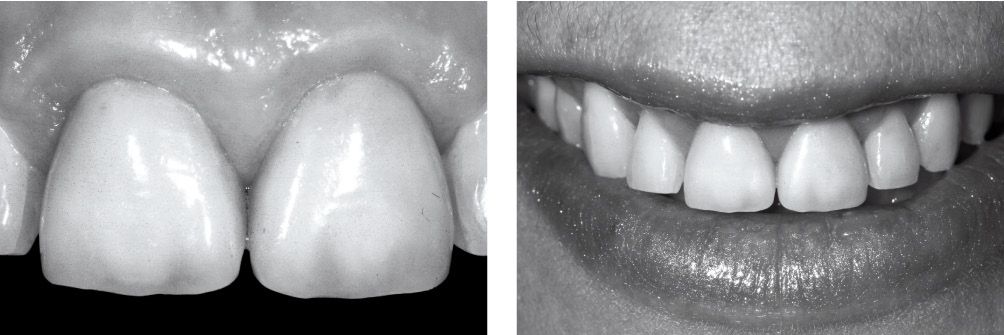

Figure 6.23r-s • Clinical outcome.

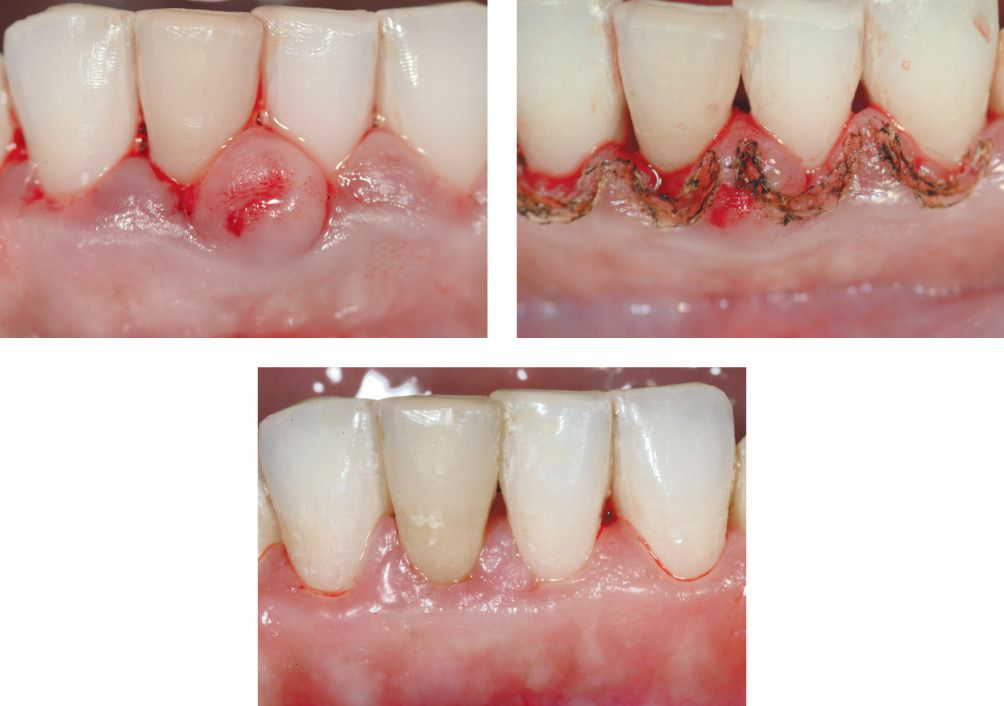

Clinical case (Fig.6.24a-p)

Clinical case: example of gingival contour remodelling.

Figure 6.24a-c • Clinical case before treatment.

Figure 6.24d-e • Assessment of periodontal health and measurement of biological width.

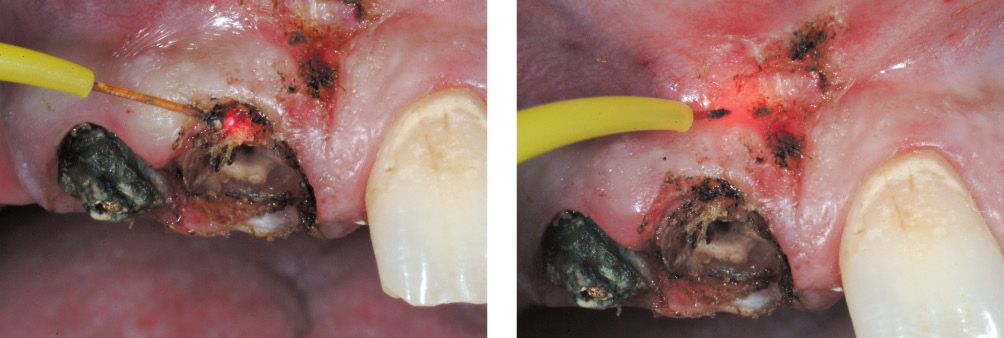

Figure 6.24f-h • Laser-assisted gingivoplasty.

Figure 6.24i-l • Tissue healing.

Figure 6.24m-p • Clinical outcome.

V. POSSIBLE TREATMENTS

1) Remodelling the gingival contour of pillar teeth

One of the aims of prosthetic and prosthetic-implant rehabilitation is to achieve a harmonious result, but dentists often find themselves having to strike a balance between the subjective state of the single patient, which makes each case a case unto itself, and general rules of practice that instead give precise indications on the results that treatments should allow [17].

Often, the operator will encounter patients presenting with very irregularly shaped gums, a problem that can affect more or less extensive segments of the oral cavity [1].

In such situations, and particularly during the preparation of the pillar teeth and the application of the first, temporary restoration in resin, it is necessary to “adjust” the gingival tissue in order to confer a harmonious and symmetrical appearance not only on the tissue but also on the teeth, given that a tooth’s length is determined by the line of the keratinised gum tissue around its neck.

Clinical case (Fig. 6.25a-y)

Clinical case: removal of portions of excess gingival tissue.

Figure 6.25a-b • Clinical case before treatment.

Figure 6.25c-d • Severely compromised pillar teeth.

Figure 6.25e-f • Laser-assisted tissue removal.

Figure 6.25g-i • Tooth preparation.

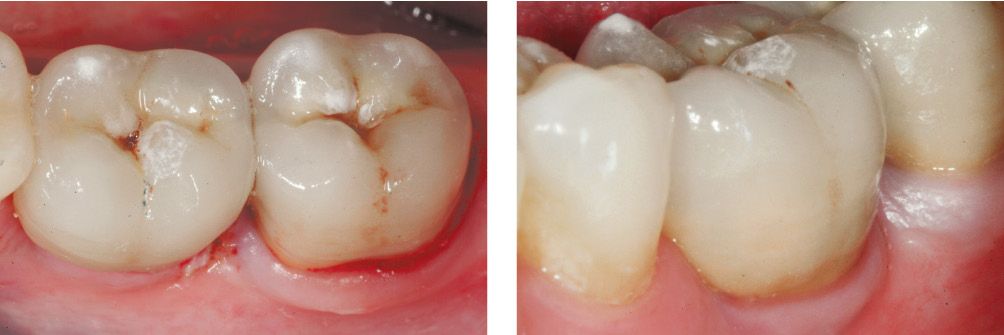

Figure 6.25l-m • Healing of gingival tissue.

Figure 6.25n-p • Impression taking using the double cord retraction technique.

Figure 6.25q-r • Tissue healing.

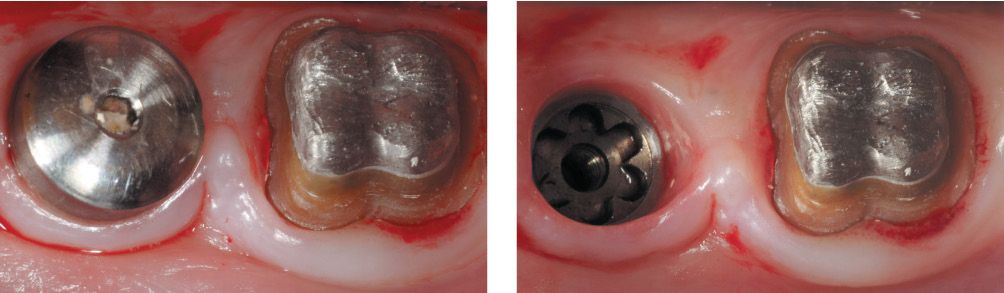

Figure 6.25s-t • Structural test.

Figure 6.25u-y • Clinical outcome.

Using the laser as a cutting instrument to modify the gums and bring them “into line” with general aesthetic canons will guarantee the patient immediate satisfaction as well as rapid and pain-free healing [2] (Figure 6.23).

Using the diode laser it is possible, with precision and preserving the gingival tissue, to trace a gum line that is not only better but also immediately visible to the operator. Set at low power (1.5-2W), the machine can initially be used like a simple dermographic pen, to trace the ideal tissue line, in other words to mark out provisionally the area that the operator intends to cut away. In this way, he can already form an idea, before having made a deep incision, of how the final result will look. In fact, just like a pencil on a sheet of paper, the laser beam leaves a fine line on the surface of the target tissue (caused by slight carbonisation of the tissue) [7,10,15,16,19, 20].

To obtain the most satisfying results, it is best, when starting to use the laser as a surgical instrument, to use it at power settings no greater than 2 Watts, and at a cutting speed that allows the instrument to be controlled effectively even by less experienced operators. The best clinical stage in which to make these tissue modifications is the preparation and the temporary restoration stage, not least because this will make it possible, after just 1-2 weeks, to evaluate, from the healing of the tissues, the practically definitive outcome (Figure 6.24). The fact that these results can be achieved in an initial phase of the treatment is highly beneficial for patients from a psychological point of view, often making them more ready to accept the modifications – presuming they have produced a functional and aesthetic improvement – and thus also more willing to tolerate the healing stages, which are sometimes straightforward and sometimes slightly more complex, depending on the magnitude of the intervention.

2) Removal of portions of excess gingival tissue

Many clinical situations are characterised by the presence of excess gingival tissue in contact with teeth that are to be the pillar teeth in a prosthetic-implant rehabilitation intervention.

An initial situation of this kind can be caused, among other things, by inflammation, accidental mechanical traumas, poor previous prosthetic restorations, drugs, or even a previous temporary prosthetic restoration if this was not carried out with due attention to the fundamental requisites of a “good” temporary restoration [17]. In each of these cases, the operator has to remove the excess tissue without causing any damage to the surrounding structures and always tracing an ideal outline of the tissues that will remain.

The use of a laser cutting apparatus in all these situations guarantees a safe and sufficiently rapid intervention in a “bloodless”, or “clean”, operating field in which the improved visibility contributes to the better aesthetic outcome.

Data available from clinical practice indicate that the diode laser, properly used, is suitable for these clinical interventions (Figure 6.25).

3) Remodelling of keratinised tissue under bridge teeth

The aim of this treatment is to confer a natural look on a prosthetic rehabilitation, and possibly to intervene in areas where the prosthesis is exerting excessive pressure on the underlying tissues.

The removal of excess gingival tissue can also be necessary in more advanced stages of prosthetic treatments, or even in the final cementing stage when uncontrolled growth of healthy tissue around a pillar tooth, under bridge teeth, or around implant teeth (Figure 6.26) can make it difficult to position the definitive restoration.

Clinical case (Fig.6.26a-f)

Clinical case: gingival tissue remodelling.

Figure 6.26a-b • Clinical case before treatment.

Figure 6.26c-d • Laser-assisted remodelling of excess tissue.

Figure 6.26e-f • Healing and clinical outcome.

4) Remo/>

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses